✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox:

Today’s Bullets:

BoJ Background

The BoJ Announcement

Implications for US Treasuries

Implications for Portfolios

Inspirational Tweet:

If you had paid attention to currencies this week—specifically the USD/JPY exchange rate—then you would know something is up in Japan.

See, the Bank of Japan made a…sort of…announcement that rocked the USD and the the Japanese 10yr JGBs in the overnight markets. Yen up, yields up, bonds down.

Oh, and US Treasuries yields up, too.

Wait, what?

If this has you confused—feeling like you stepped into an episode of Stranger Things—do not fret. We’re going to unpack and walk through this important dynamic, nice and easy as always, today.

So, grab your favorite mug of coffee, sit back, and soak it all in. It’s Informationist time.

Join the Informationist community to get access to subscriber-only posts and the full archive + ask questions and participate in the comments with other awesome 🧠 subscribers!

🧐 BoJ Background

First, a little backdrop and backstory for this episode. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has been a key player in the world bond show, and in a theme common to virtually all central banks, their recent actions have had a major impact to their bond market and the yen.

Specifically, Japan has been experiencing an opposite dynamic to the US and other developed nations, as they’ve had strong pressures of deflation over the last number of years.

To battle this deflation—or falling prices and falling nominal GDP—the Bank of Japan has been using what is called yield curve control to keep interest rates on their bonds artificially low. They do this by buying bonds in the open market in order to keep rates from rising.

Remember: As a bond price rises, the effective yield of that bond falls, and vice versa. And so, as the BoJ buys its own bonds, it keeps yields low.

How low?

Well, during 2022, the BoJ held its own 10yr Japanese Gov Bond, or JGB, at ~25bps yield. It bought and bought and bought its own JGBs, any amount that the market sold, to keep the yield from rising.

Their plan:

Low yields → cheaper capital for companies and consumers → higher profitability and higher spending → higher prices → less deflation (and hopefully some inflation)

Problem was, the rest of the world had already ended ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) and were raising rates to battle inflation in their regions.

For instance, the US Fed had already raised rates to 4% by end of 2022.

The result?

Japanese investors sold JGBs to buy USTs for the higher yield. And why not? After all, you could buy a 10yr UST that yielded 3.75% to 4% more than a similar 10yr JGB yielding only 25bps.

This put tremendous pressure on the yen, as investors sold JGBs and then turned their yen into USDs to buy USTs.

A near-perfect relationship, the spread between the yields and the exchange rate between currencies move pretty much in lock step:

This dynamic is called interest rate parity, and I wrote all about it here, if you want some additional color on that:

Bottom line, with all the pressure of investor selling, the BoJ ended up buying so many of their own bonds that they’re now the single largest holder of JGBs on the planet.

You read that right.

In fact, the BoJ owns over 50% of all JGBs now.

Stranger Things, indeed.

And in the beginning of 2023, the BoJ had little choice but to back off its endless purchase plan and move the rate it would buy them at to .5%.

This shocked the markets, especially hedge fund speculators, and the yen gained vs the USD, as the 10yr JGB snapped right to the new yield of .5%.

And now, six months later, the BoJ just did it again.

📣 The BoJ Announcement

This past week, the BoJ moved the rate at which they would backstop their 10yr JGB to 1%. That’s another .5% move higher, effectively doubling the rate, again.

The result?

The 10yr JGB yield jumped, the USD fell vs JPY, and the 10yr UST yield jumped. At least initially.

But the BoJ got a bit crafty in their announcement this time. And instead of simply declaring a new ceiling for the 10yr rate, they called the .5% level a ‘suggestion’, with a new hard cap at 1%.

And this now has investors confused.

Is .5% still a limit or not? Will they backstop the JGBs there for a certain amount of selling before allowing the rate to move toward 1%? How long until it goes to 1%?

The market is unsure, but the 10yr JGB yields immediately jumped over the .5% rate.

But the message is clear: the BoJ is backing off its yield curve control program. Or at least trying to. They know they must eventually allow yields to gravitate to more normal or natural market-driven levels.

Unless of course they want to own 100% of their government bonds someday.

But this move has serious implications for the remaining sovereign bond market. And in particular, the US Treasury.

😨 Implications for US Treasuries

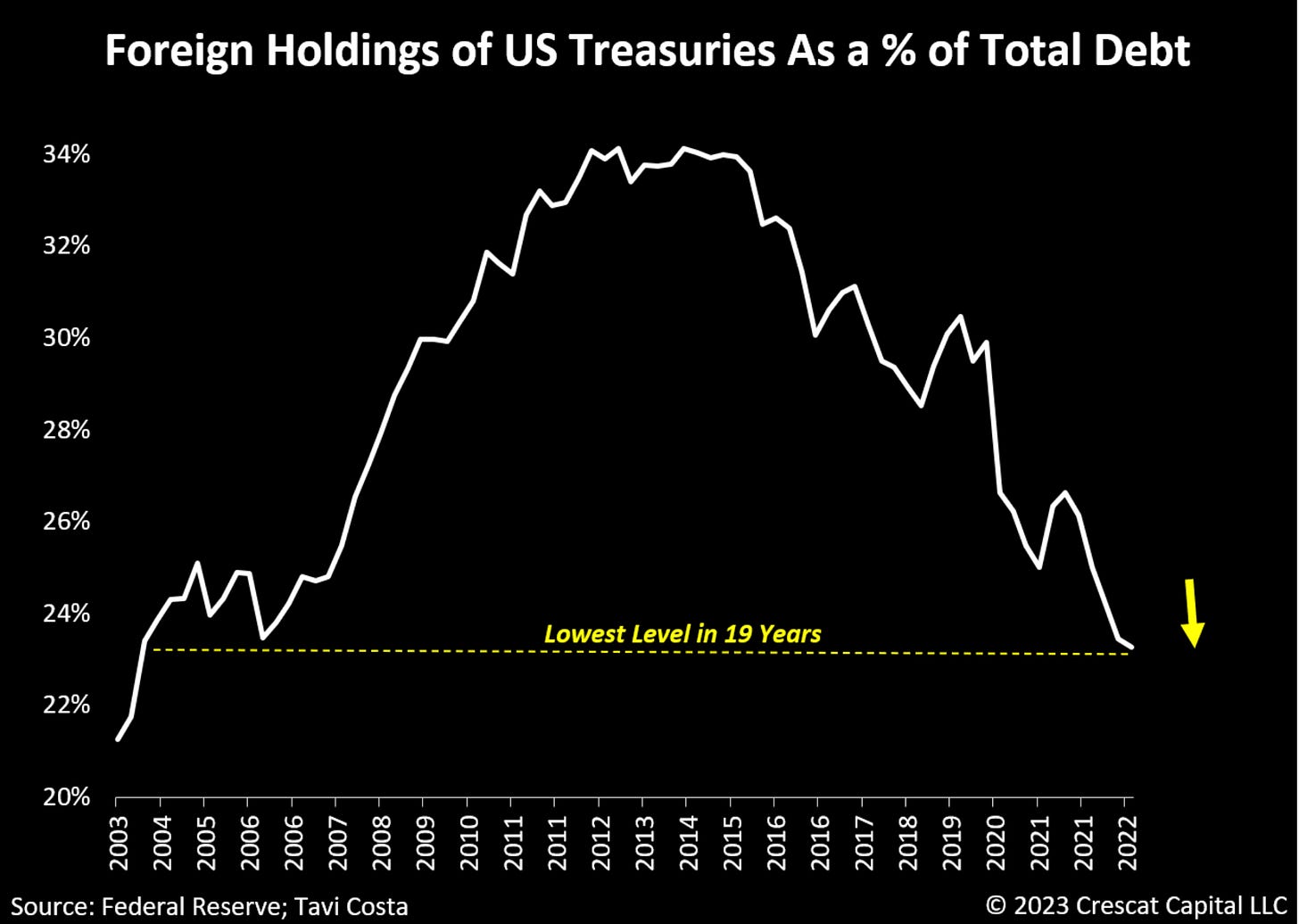

We’ve been talking quite a bit lately about the falling demand for US Treasuries around the world.

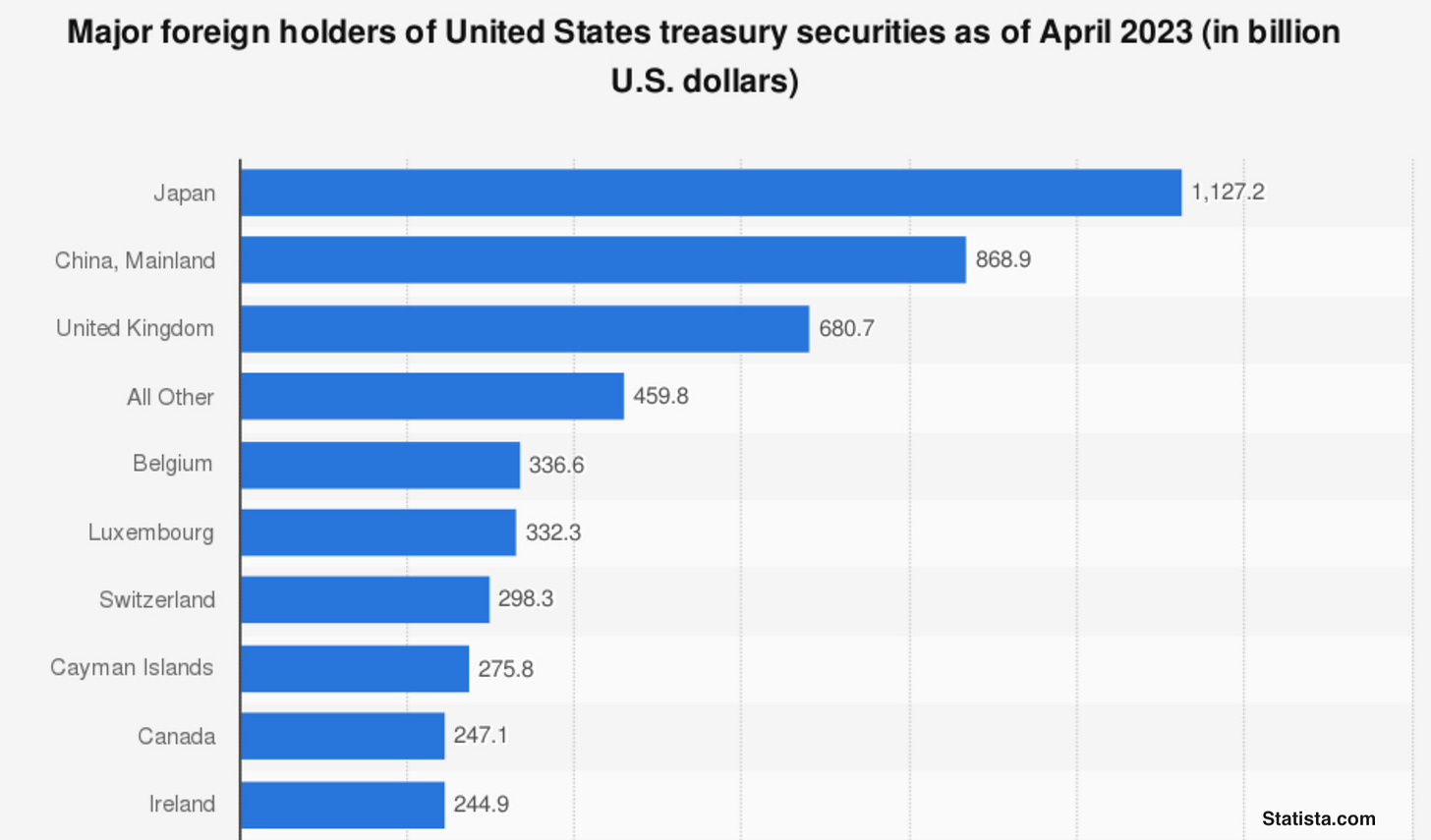

Russia sold their USTs, China has been selling theirs, and as we showed above, Japan has been selling USTs in order to use US dollars to support the yen.

And now, if the JGBs are going to soon yield enough to attract local investors, then the US loses its largest marginal buyer of US Treasuries:

At the exact same time that the US spending deficit is absolutely exploding, in no small part due to the interest expense on its own debt:

That’s right, the US government spends nearly $1T per year, on interest. Which just means higher deficits, and…?

You got it.

The need for the US Treasury to issue even more debt. AKA, the debt spiral.

If you have not been following me, or want to learn more about this in detail, I wrote a whole article about the debt spiral that you can find here:

And this would put the US Treasury in the hot seat, so to speak, having to step in at some point to be that marginal buyer, keeping the Treasury market liquid by gobbling up its own USTs.

The relevant question may just be: when?

🤓 Implications for Portfolios

Once again, we’re talking about massive amounts of necessary liquidity and the potential for significant expansion in the M2 money supply.

But we are currently entering a precarious period for markets, IMO.

With lagging effects of Fed tightening, the rise in credit portfolio risks, rising corporate default rates, rise in consumer credit rates and balances, all point to either a looming recession, or a credit event.

Or worse: both.

And tactical treatment of portfolio exposures is not just prudent, but a must at this point.

And as I mentioned last week: good news for all paid subscribers: I’ve been working hard on a new feature that you will have access to in the near future.

For now, many of you already know that I personally hold a large allocation to FDIC+ insured cash as well as short-term Treasuries and hard monies: gold, silver and Bitcoin. I also have allocations to certain sector ETFs that I’ve been rotating as we enter this phase of the economy.

But like I said, we will get into much more detail on that soon! So, please stay tuned!

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about the BoJ and JGBs and implications for the UST market. Before leaving, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest.

And don’t forget to leave a comment or answer a comment in our awesome 🧠 Informationist community below!

Talk soon,

James✌️

Great information from the Informationist. How soon is soon when it comes to the new feature? Also can you refer us to some good basic instruction about how the bond markets work?

Hi James,

Wondering in your opinion what has prevented a significant recession and/or credit event occurring yet and forcing this elusive "pivot"? Hard for me to imagine its really this much of a lag but surely defer to your expertise on this one...Can you perhaps give your difference in the odds of this "soft landing" narrative occurring presently versus 12 months ago?

Thanks,

Ryan