💡 The $6.6 Trillion Broken Promise

Issue 205

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

The Original Accord

How the Fed Broke the Deal

What Warsh Actually Wants

The Bull Case vs The Trap

Investment Implications

Inspirational Tweet:

If you follow financial news, you’ve probably heard the name Kevin Warsh a lot lately.

Trump’s pick to replace Jerome Powell as Fed Chair. Former Fed Governor. Stanford guy. Hawks love him. Doves fear him.

But there’s one idea Warsh floated last year that most people have glossed right over.

A new accord between the Fed and the Treasury.

If that sounds like boring bureaucratic stuff, I promise you it’s not. The last time the Fed and Treasury struck an accord was in 1951. That deal shaped everything about how central banking works in America.

How interest rates get set. How much the government can borrow. How much your money is actually worth.

And Warsh thinks it’s time for a new one.

So what was the original accord? Why does Warsh think it’s broken? And what would a new version actually mean for you, your portfolio, and the dollar in your pocket?

All great questions that deserve serious consideration and answers, ones that we will sift through, nice and easy as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a big cup of coffee and settle into your favorite seat for a deep look at the most important deal you’ve never heard of with this Sunday’s Informationist.

Partner spot

The cracks in the foundations of money are becoming harder to ignore. Persistent deficits, rising debt, and central bank behavior are quietly reshaping how investors think about preservation and risk.

In my latest report, The Debasement Trade, I walk you through:

Why debasement is structural, not cyclical

How inflation and financial repression challenge familiar portfolios

Why gold tends to move first—and bitcoin often moves further

You can download the report here:

🏛️ The Original Accord

To set the stage today, let’s head back to 1942.

The United States had just entered World War II. And wars cost money. A lot of money.

The Treasury needed to borrow, and borrow big. But here’s the problem. If interest rates rise while you’re trying to finance a war, your borrowing costs explode. Every percentage point higher means billions more in debt payments.

So the Treasury went to the Federal Reserve and made a request.

Keep rates low. No matter what.

The Fed agreed. It pegged short-term Treasury bill rates at 3/8 of a percent. And it put an unofficial cap on long-term bonds at 2.5%.

To maintain those rates, the Fed had to buy government bonds. Lots of them. Every time the market tried to push yields higher, the Fed stepped in and purchased more debt. That meant printing more money. Which meant more inflation.

But it was wartime. You do what you have to do.

The problem? The war ended, but the rate peg didn’t.

By the late 1940s, inflation was running hot. Between June 1946 and June 1947, consumer prices rose 17.6%. The following year, another 9.5%.

The Fed wanted out. It wanted to raise rates, fight inflation, do what a central bank is supposed to do.

President Truman said no.

He and Treasury Secretary John Snyder wanted cheap borrowing to continue. They had war bonds outstanding, millions of Americans holding them, and they didn’t want those bonds losing value.

So the Fed was stuck. Forced to keep buying government debt. Forced to keep rates artificially low. Forced to watch inflation eat away at the purchasing power of the very citizens it was supposed to protect.

Then came Korea.

When the Korean War started in June 1950, everything got worse. More government spending. More borrowing. More pressure on the Fed to keep the money spigot open.

By February 1951, inflation hit an annualized rate of 21%.

Twenty-one percent.

The Fed had had enough.

In January 1951, Truman invited the entire Federal Open Market Committee (you know, the FOMC) to the White House. After the meeting, the President released a statement claiming the Fed had “pledged its support to maintain the stability of Government securities.”

One problem. The Fed had made no such pledge.

Fed Governor Marriner Eccles, furious at the White House's false claim, leaked the FOMC's own minutes to the press on his own authority. In his words, "The fat was in the fire.”

The standoff became public. And it forced a resolution.

On March 4, 1951, the Treasury and the Fed issued a joint statement. They had “reached full accord with respect to debt management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose and to assure the successful financing of the government’s requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt.”

Read that last part again slowly.

“Minimize monetization of the public debt.”

The Fed would no longer be the government’s ATM. It could set interest rates independently. It could fight inflation without asking permission from the White House.

That one agreement laid the foundation for everything we know as modern central banking.

It was, quite literally, the birth of Fed independence.

And for the next half century, it more or less worked.

Until it didn’t.

🤥 How the Fed Broke the Deal

For decades after the accord, the Fed mostly stayed in its lane.

It raised rates when inflation ran hot. It lowered them when the economy slowed. It held a modest portfolio of short-term Treasuries to manage the money supply, and it left the bond market alone.

Then came 2008.

When the housing bubble burst and the financial system nearly collapsed, the Fed did something it hadn’t done since before the accord. It started buying massive amounts of government debt.

They called it quantitative easing, QE for the Wall Street crowd. A fancy term for the Fed creating money out of thin air and using it to buy Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities directly from the market.

Incidentally, I’ve written all about QE before and how money printing works. If you want to learn about that or revisit the concept, you can find that article right here:

The goal? Push long-term interest rates down. Make borrowing cheaper. Or as they like to say, stimulate the economy.

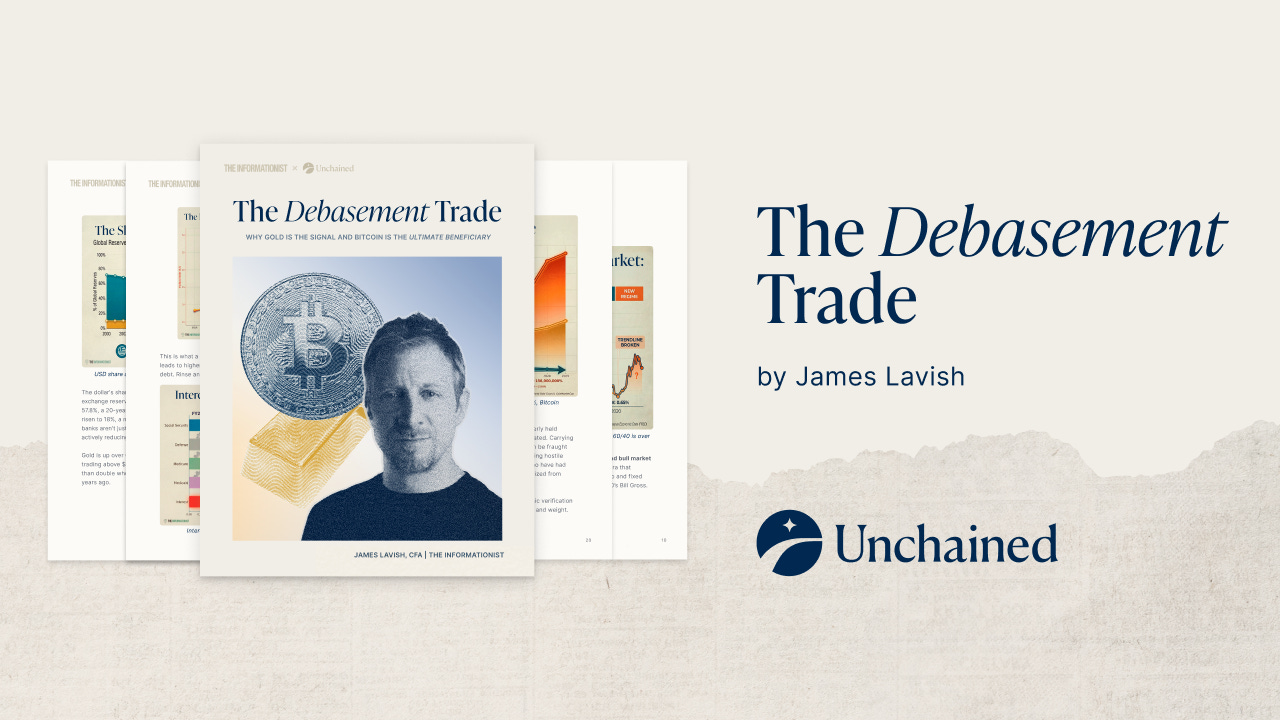

The Fed’s balance sheet, which had sat below $1 trillion for its entire history, pretty much doubled overnight. Then it doubled again.

QE1. QE2. Operation Twist (another fancy term for buying long-dated bonds and selling short-dated bonds, get it? Twist). QE3.

By 2014, the Fed held over $4 trillion in bonds. Four times what it held before the crisis.

Now, officials promised this was merely temporary. Emergency measures for emergency times. They would shrink the balance sheet back to normal once the crisis passed.

To be fair, between 2017 and 2019, the Fed did let some bonds mature without replacing them. The balance sheet dipped from $4.5 trillion to about $3.8 trillion.

Then the repo crisis of 2019 occurred, and the Fed immediately stopped QT and started QE again, buying bonds to “stabilize the credit and Treasury markets.”

This was a trickle of buying in comparison to the last time.

But then WHAM-O!

The COVID “crisis”.

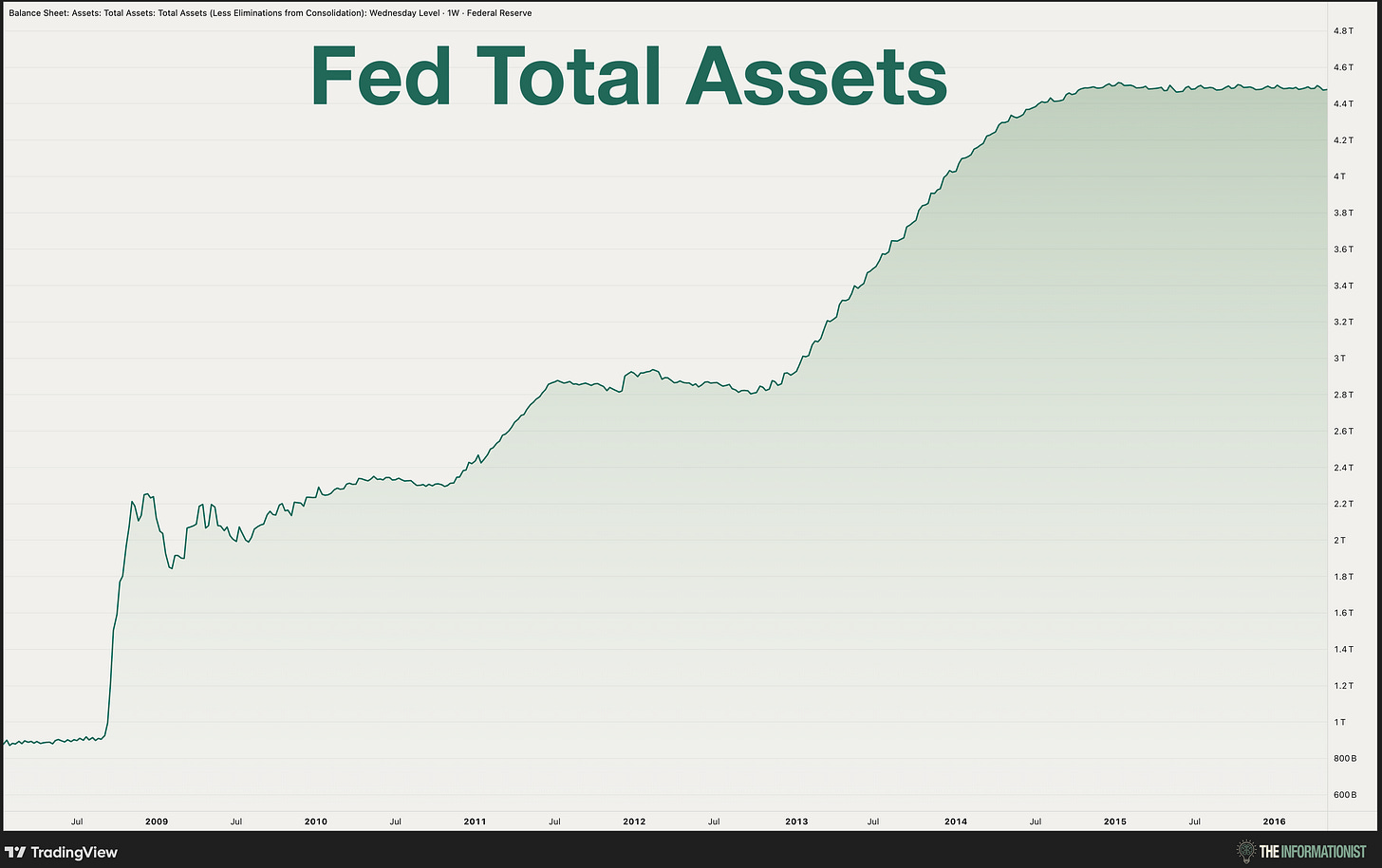

And the Fed went right back to the Big Boy Bond Buying Playbook. The super duper special edition.

In a matter of months, the balance sheet exploded from $4 trillion to nearly $9 trillion. The Fed was buying $120 billion in bonds every single month. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, gobbling them up like my bulldog snarfs down ground beef.

But wait.

Remember the accord? “Minimize monetization of the public debt.”

In 2020, the federal government ran a $3.1 trillion deficit. In 2021, another $2.8 trillion. And the Fed was right there, buying trillions in government bonds, effectively financing those deficits with newly created money.

That is pure monetization. Full stop.

Now, nobody at the Fed would use that word. They’d say they were “ensuring the smooth functioning of Treasury markets” or “supporting the economic recovery.”

But let’s be honest here for a moment, shall we?

The government spent. The Treasury borrowed. And the Fed printed money to buy that debt.

Exactly the same as the 1940s. Exactly what the 1951 accord was designed to end.

And we all know what came next.

Massive inflation.

Consumer prices surged to 9.1% in June 2022. The highest in 40 years. Just like the post-war period, all that money creation eventually showed up in the price of everything.

So the Fed pivoted again and started raising rates aggressively and shrinking its balance sheet. Quantitative tightening, the almighty QT.

But here’s the thing.

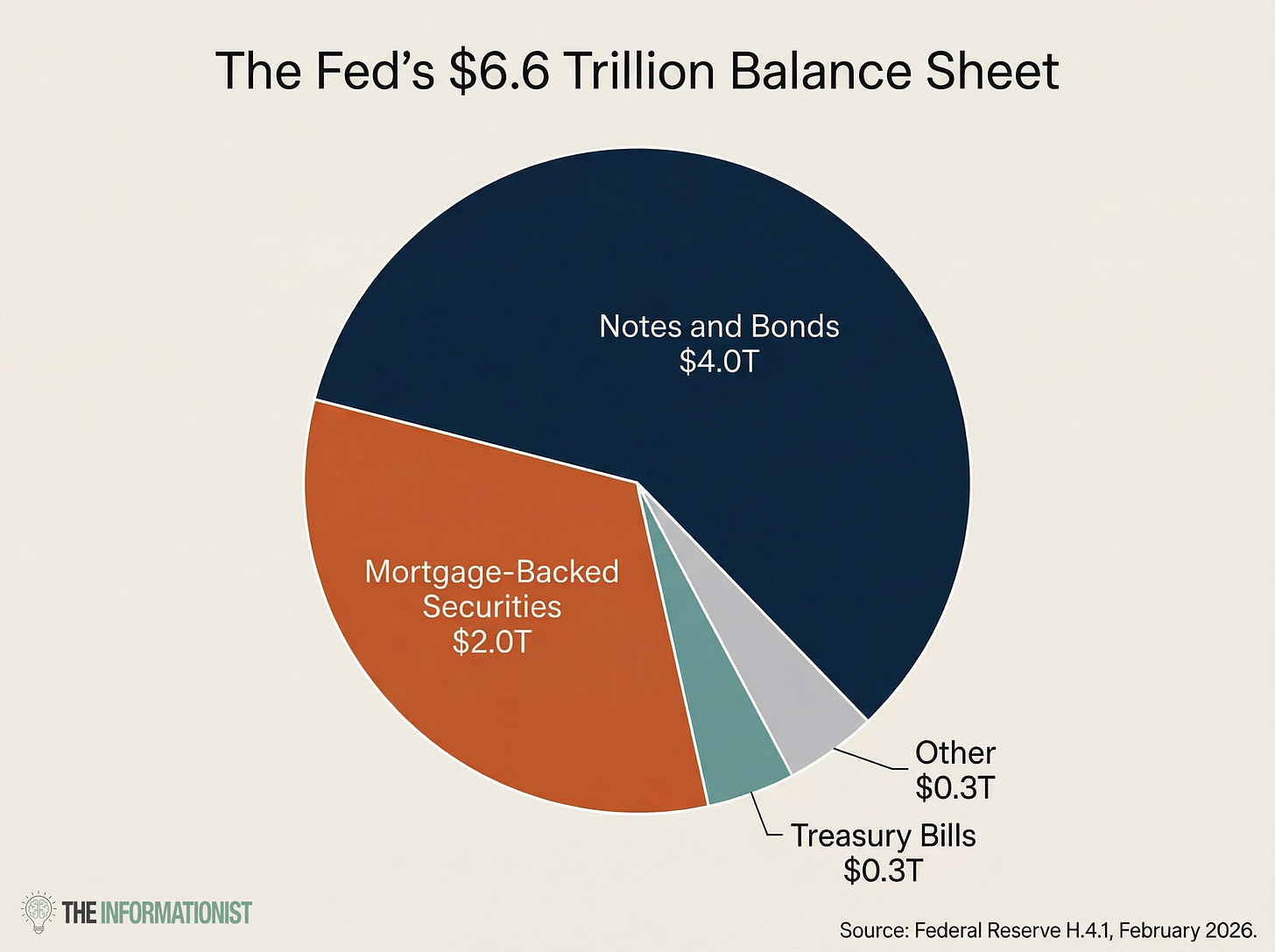

Even after years of QT, the Fed’s balance sheet today is still over $6.6 trillion (see the chart above). That’s more than six times its pre-crisis level.

And look at what it holds.

60% in notes and bonds. Long-term government debt.

31% in mortgage-backed securities. The Fed is still one of the biggest players in the housing market.

Makes you wonder why prices just refuse to come down, doesn’t it? Like this maaaaay be a factor in that?

And just 4.4% in Treasury bills. Short-term, low-risk, easy to roll off.

In other words, the Fed’s portfolio looks nothing like what it did before 2008. It’s stuffed to the gills with long-term government debt and mortgage securities, exactly the kind of holdings the 1951 accord was meant to prevent.

The accord said the Fed would stop being the government’s financier.

And yet, here we are, seventy-five years later, with a Fed that’s holding $6.6 trillion of the government’s paper.

The deal didn’t stick.

🥸 What Warsh Actually Wants

Stage right, enter Kevin Warsh.

Some of you know that I took a good hard look at Kevin Warsh recently, a whole article was dedicated to his nomination. If you’re new, you can find that article here:

TL;DR for today’s purposes: Warsh served as a Fed Governor from 2006 to 2011. He was there for the financial crisis. He watched QE get launched in real time.

And he didn’t like it.

When the Fed launched QE2 in November 2010, Warsh was its fiercest internal critic. He told his FOMC colleagues point blank, "If I were in your chair, I would not be leading the Committee in this direction."

He ultimately voted yes, bowing to Bernanke, and one week later he published a Wall Street Journal op-ed laying out exactly why he thought it was a mistake. Three months later, he resigned.

His argument?

Large-scale bond buying was dangerous. It blurred the line between monetary policy and fiscal policy. And once you start, it’s almost impossible to stop.

He was right on all three counts.

Now, as Trump’s nominee to replace Powell, Warsh has put forward his biggest idea yet. A new accord between the Fed and the Treasury.

Here’s what he said on CNBC just six months before the nomination:

“If we have a new accord, then the Fed chair and the Treasury secretary can describe to the markets plainly and with deliberation, ‘This is our objective for the size of the Fed’s balance sheet.’

Did you catch that key phrase? Plainly and with deliberation.

Truthfully, nobody really knows the plan. How big should the Fed’s balance sheet be? $4 trillion? $3 trillion? Nobody’s said. How fast should it shrink? Nobody’s committed. What should it hold? Long bonds? Short bills? MBS? The answer changes depending on who you ask.

Warsh wants to end that ambiguity.

His proposal, as best as anyone can piece it together, has a few moving parts.

First, define a target size for the Fed’s balance sheet and communicate it clearly. No more guessing. No more “data dependent” hand-waving. A number, a timeline, and a plan.

Period.

Second, coordinate with Treasury on debt issuance. If the Fed is going to shrink, Treasury needs to adjust how much and what kind of debt it sells. You can’t have one arm of the government dumping bonds while the other arm is pulling back from buying them. That’s a recipe for a market seizure.

Third, and this is the big one, shift the Fed’s holdings from long-term bonds to short-term Treasury bills. Get out of the mortgage market entirely. Stop holding 10-year and 30-year government debt. Buy bills that mature in weeks or months, not years or decades.

Deutsche Bank ran the numbers. Under Warsh, T-bills could go from less than 5% of the Fed’s portfolio to as high as 55% over the next five to seven years.

That would be a fundamental transformation of how the Fed operates in bond markets.

Somehow, Warsh insists this is not a return to pre-1951. He’s not proposing that the Fed finance the government’s spending. He’s arguing the opposite. That a clear framework would actually restore the Fed’s independence by getting it out of the business of holding trillions in long-term government debt.

And Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent appears to be on board. He’s made similar comments about the Fed maintaining QE for too long and has argued that large-scale bond buying should only happen during “true emergencies.”

So, on paper, this sounds pretty good. Right?

Restore the spirit of the original accord. Shrink the balance sheet. Get out of long-term bonds. Let markets set rates.

But yeah, not everyone is buying it.

And why would they? I mean take one more look at where we actually are.

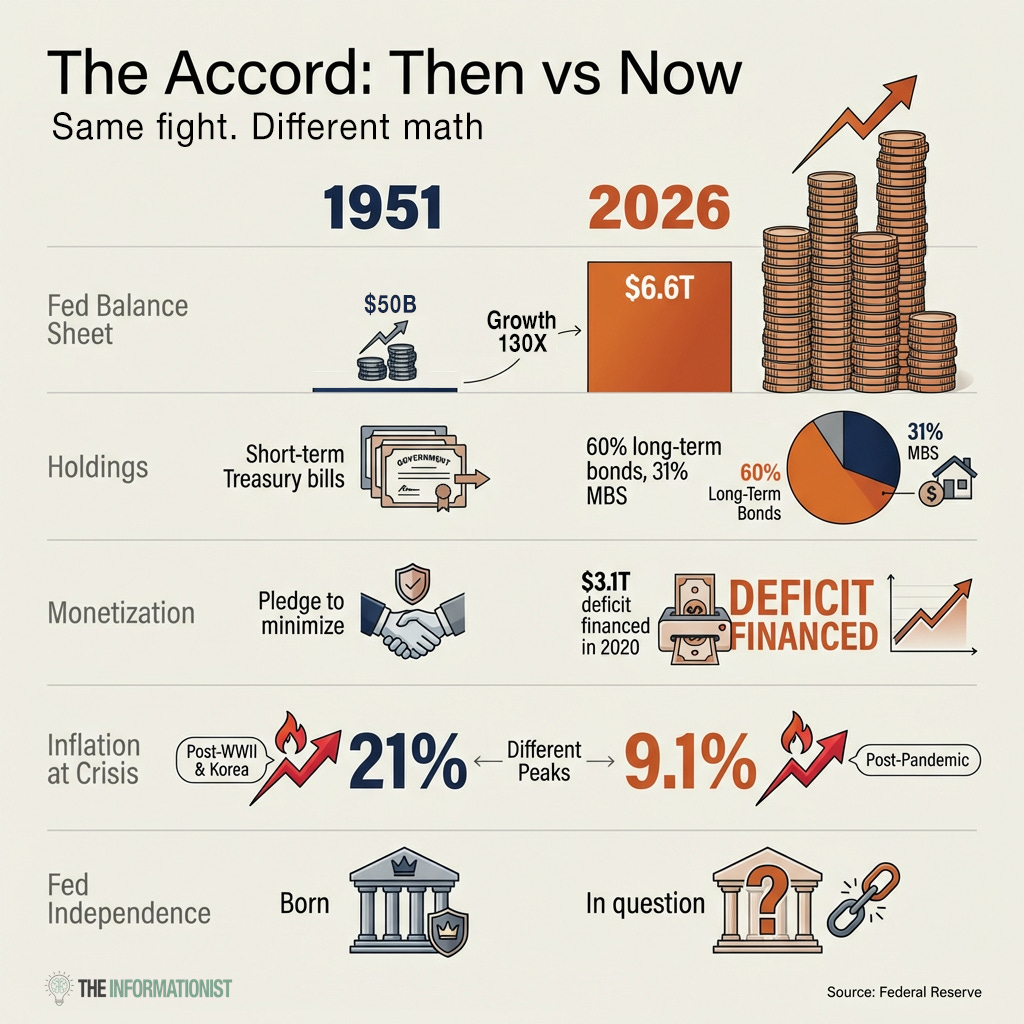

About $50 billion to $6.6 trillion. Short-term bills to long-term bonds and mortgage securities. From a solemn pledge to minimize monetization to an explosive $3.1 trillion in deficit financing in a single year.

The numbers got bigger. The tolerance got smaller. And the debt got a whole lot harder to walk away from.

Same fight. Totally different math.

🐂 The Bull Case vs The Trap

Let’s lay out both sides. Because this is one of those debates where smart people completely disagree.

The Bull Case

Supporters of a new accord argue it would do three things.

One, it ends the era of QE as a default tool. If the Fed commits to a smaller, bill-heavy balance sheet, it can’t just fire up the printing press every time markets get nervous. Emergency bond buying would require an actual emergency, not just a bad week in stocks.

Two, it restores real price discovery in bond markets. Right now, the Fed holds so much long-term debt that it distorts the entire yield curve. Mortgage rates, corporate borrowing costs, and government bond yields are all influenced by the Fed’s massive presence. Pull that out, and markets can finally do their job.

Three, it gives investors clarity. No more wondering if the Fed will surprise everyone with another round of QE or suddenly accelerate QT. A written framework, jointly announced with Treasury, would let everyone plan accordingly.

Bessent has made exactly this point. In a world where the Fed’s balance sheet actions are predictable and mapped to Treasury’s debt issuance plan, markets get less volatile. Borrowing costs stabilize. Confidence improves.

Sounds great…in theory.

The Trap

Others see something quite different. Alarming, in fact.

Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors, put it bluntly. He called the new accord “less about protecting the Fed and more like a yield curve control framework.”

Good ol’ yield curve control. YCC to pros around here.

It’s what Japan has been doing for years. The Bank of Japan explicitly targets long-term interest rates, buying whatever it takes to keep them where it wants. It’s the most extreme version of a central bank financing government debt. And it has decimated the yen.

Now, Warsh would say his proposal is the opposite of YCC. He wants the Fed to step back from the bond market, not step deeper in.

But here’s the thing.

If the Fed and Treasury are publicly coordinating on balance sheet size, debt issuance schedules, and the composition of holdings, where does monetary policy end and fiscal policy begin?

Good question.

Krishna Guha of Evercore ISI thinks that this framework could give Treasury a “soft veto” over the Fed’s tightening plans.

I mean, what if the Fed wants to shrink faster but Treasury says the market can’t handle more bond supply?

Yeah, we’re going to have to go ahead and ask you to not do that.

Thaaaaaanks.

And there’s an even bigger problem.

As many of you know, I’ve been highlighting that the US government is running deficits of over $2 trillion a year. Interest on the national debt has crossed $1 trillion annually. The Congressional Budget Office projects it will hit $1.8 trillion by 2035.

Can any Fed chair, even one who genuinely believes in independence, really say no to a government drowning in their own debt?

The 1951 accord worked because deficits were manageable. The government could afford to pay market rates on its borrowing. Today, with $36 trillion in debt and $1 trillion in annual interest costs, the math is starkly different.

If long-term rates rise because the Fed steps back from the bond market, the government’s borrowing costs explode. And if borrowing costs explode, the pressure on the Fed to step back in becomes overwhelming.

The trap.

Restore market discipline, and the government can’t afford its own debt. Keep suppressing rates, and the currency keeps getting debased.

There’s no clean off ramp. There never was.

💰 Investment Implications

OK so let’s bring this one home, shall we?

What does all of this actually mean for you and your investments?

Scenario 1: The Accord Works as Advertised

Warsh and Bessent pull it off. The Fed shrinks its balance sheet in an orderly way. Treasury adjusts issuance accordingly. Long-term rates rise modestly as the market takes over price discovery, but it’s gradual and manageable.

In this world, bonds take a hit in the short term as rates adjust higher. But over time, the bond market becomes healthier. Real yields reward savers. The dollar strengthens as the market gains confidence in fiscal discipline.

There’s one little catch though. This requires Congress to actually balance the budget.

Uh huh. They’ll make Area 51 a theme park before they do that.

Scenario 2: The Accord Is Window Dressing

The new accord gets announced with a lot of fanfare but changes little in practice. The Fed shifts some holdings toward bills but keeps a massive balance sheet. Treasury keeps issuing debt at the same pace. The coordination is real, but the discipline isn’t.

Markets shrug. Yields stay range-bound. Nothing really changes. The can gets kicked further down the road.

I would say that this is actually the most likely outcome, if we’re being honest. BofA’s analysts said as much, projecting “minimal market impact” from a new accord.

Scenario 3: The Math Forces Their Hand

This is the one that keeps me up at night.

Rates rise. Deficits keep growing. Interest costs spiral from $1 trillion to $2 trillion+. And at some point, the government simply can’t afford to pay market rates on its debt.

So the Fed steps back in. New name, new framework, same result. The central bank buys government bonds to keep rates manageable, and the currency pays the price.

This is the scenario where hard assets win. Gold, silver, Bitcoin. Things that can’t be printed, debased, or diluted by a government that needs to finance its own survival.

And if you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you know I believe this is the most probable path over the long term. Not because anyone wants it. But because the math demands it.

What to Watch

Warsh’s confirmation hearings. Pay attention to what he says about the balance sheet and any specifics about a new accord.

The first FOMC meeting under new leadership. Actions speak louder than frameworks.

Treasury’s quarterly refunding announcements. If issuance shifts meaningfully toward bills, the accord is real. If not, it’s just talk.

The yield curve. If long rates start moving higher without the Fed intervening, that’s the market testing whether independence is genuine.

And the price of gold. Because gold has a way of telling you the truth about currency debasement long before anyone in Washington admits it.

Here’s what stays with me.

In 1951, a Fed governor leaked confidential minutes to the press because he refused to let the government use his institution as a printing press. That act of defiance created the most important boundary in modern finance.

Seventy-five years later, we’re having the same conversation. Different names. Different numbers. Same fundamental question.

Can a central bank say no to a government that can’t afford to hear it?

Warsh says yes. Maybe he means it. Maybe he’s the guy who actually draws the line.

But the debt is $36 trillion. The deficits are $2 trillion a year. The interest alone is $1 trillion and climbing.

And every single time in history that a government has found itself in this position, the answer has been the same.

Print.

The names change. The frameworks change. The accords change.

But the math?

That never changes.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little smarter knowing about the 1951 accord, why it matters more than ever, and what a new version could mean for your money.

If you want this kind of deep-dive analysis every single week, not just once a month, join the paid Informationist family right here:

And if you enjoyed this free version of The Informationist and found it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️

Hard to Hit “Like”…. But thanks for the Fireside Conversation.

Maybe, by the 4th of July, we will all be headed to the Woodshed for the next dose of reality.

“May You Live in Interesting Times”

Making Area 51 a theme park is actually a great idea for the government to raise additional revenue. More ideas like that and maybe they could balance the budget!