Money Printing Simplified

Issue 114

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today's Bullets:

Money Supply Basics

Treasury Bond Basics

How Money is 'Printed'

Inspirational Tweet:

If you hopped onto Twitter in the last 24 hours, you likely saw this clip and heard the confusion coming from Jared Bernstein, the Chair of the United States Council of Economic Advisers.

Yes, the group that advises the White House on economic policy.

There was a whole lot of dunking on the guy and some sincere worry over the state of our government finances, considering The President's Chief Economist seems to have no idea how Treasury bonds and money printing works.

But let's face it. This stuff is super confusing and hard to grasp.

(You would hope our leading economist would get it, but hey, this is not going to be a pile-on).

Instead, we are going to break the concepts down, nice and simple as always, here today.

So, grab a big ol' cup of coffee, settle into your favorite chair, and let's unpack money printing with The Informationist.

🧐 Money Supply Basics

To understand 'money printing' we must first understand money basics. Or rather, 'money supply' basics.

We will keep it super high level here and easy to understand. If you want a deeper dive into the concepts, I wrote a whole newsletter about money supply a while ago that you can find here:

For the TL;DR crowd, let's define Narrow Money (M0 and M1) and Broad Money (M2) quickly.

Narrow Money

At the most restrictive end of the money supply measures, we have what is called narrow money, or M0 (‘em-zero’). This includes only currency in circulation and cash kept in reserve by banks. Hence, M0 is often referred to as the monetary base.

Moving up one notch, we have what is known as M1.

M1 includes all of M0 plus demand deposits, as well as any outstanding traveler’s checks. Demand deposits are simply liquid deposits in bank accounts that can be withdrawn by a customer at any time, i.e., customer checking and immediately accessible savings accounts.

Hold up, you say, banks don't actually have all this cash in the safe, ready for withdrawal, right? Didn't we learn this with the bank collapses this past year?

Exactly.

Banks don’t hold all your cash in their vaults. They use risk analysis estimate how much needs to be available at various branches in absence of a run at the bank.

The rest is just 0s and 1s on a digital ledger that they keep.

In any case, M1 includes this digital cash that could be withdrawn (including those traveler’s checks), but stops there. Hence, M1 is often referred to as narrow money.

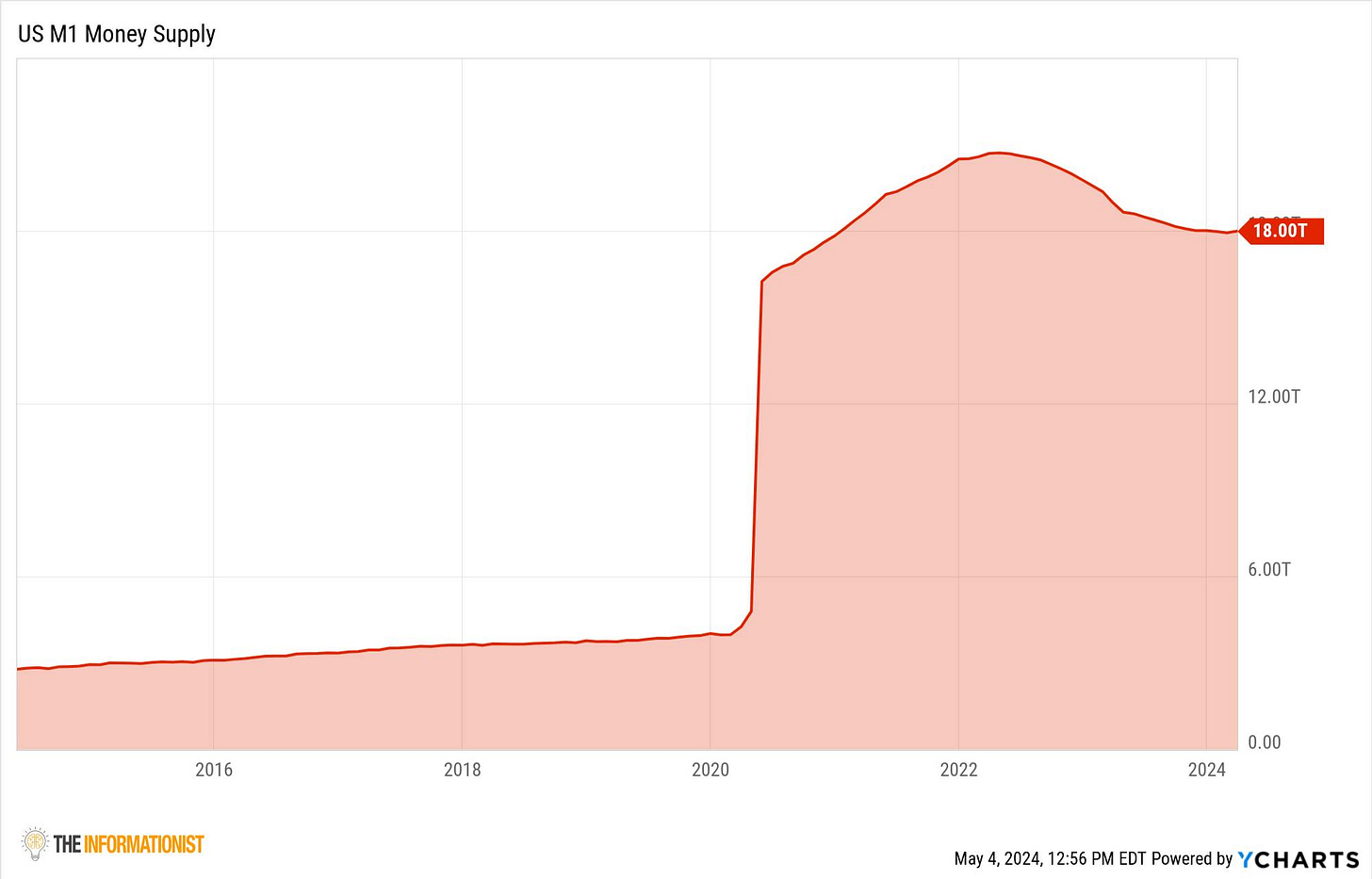

Here’s how much M1 is out there in US Dollars:

I know what you're thinking:

What the heck happened in 2020 that cause the M1 money supply to skyrocket higher?

Well, as you may have guessed, that has to do with money printing, and we will get to that in a bit. But let's first unpack the next level of money supply, the wider calculation of it, called broad money.

Broad Money

Moving our scope out a little bit, broad money includes all of M1 and more and can be defined as M2.

M2 includes all of M1 plus money market savings deposits, time-restricted deposits under $100,000 (i.e., Certificates of Deposit), and shares of money market mutual funds. In other words, M2 includes all money that is held in cash equivalent accounts, liquid and semi-liquid.

Expanding to M2, here is the amount in USD out there today:

You can see how the chart of M2 is much more gradual in its expansion after 2020, and how it takes a while to 'trickle down' into individual's accounts.

This has to do with the Cantillon Effect. A concept named after Richard Cantillon, an 18th-century economist, the Cantillon Effect describes how those who receive new money first (e.g., banks, government, or financial institutions) benefit, while others further down the line and removed from the direct receiving of money experience delayed effects.

Now let's explain what Jared Bernstein had so much difficulty describing (and apparently understanding himself).

God help us all.

The US Treasury Bond.

🤓 Treasury Bond Basics

In the absolute most basic form of definition, a US Treasury Bond is a bond issued by the US government. This is no different than a bond issued by Apple or Microsoft or Tesla.

It is the country (or company) borrowing money from the people who buy the bond.

And what happens when you borrow money?

Right. You pay interest to the one(s) who lent it to you.

Just like you pay the bank interest on your mortgage. You borrowed money from the bank to buy the house, you pay the bank interest for that loan.

Simple.

Now. We all know that the government has been borrowing a massive amount lately. This is because the government operates in a deficit (it spends more than it receives in tax revenues) and it makes up the difference by borrowing it. This is the US Public Debt.

How much has the US borrowed, and how much does it owe everyone who lent that money to it?

Ouch.

34.6 Trillion Dollars.

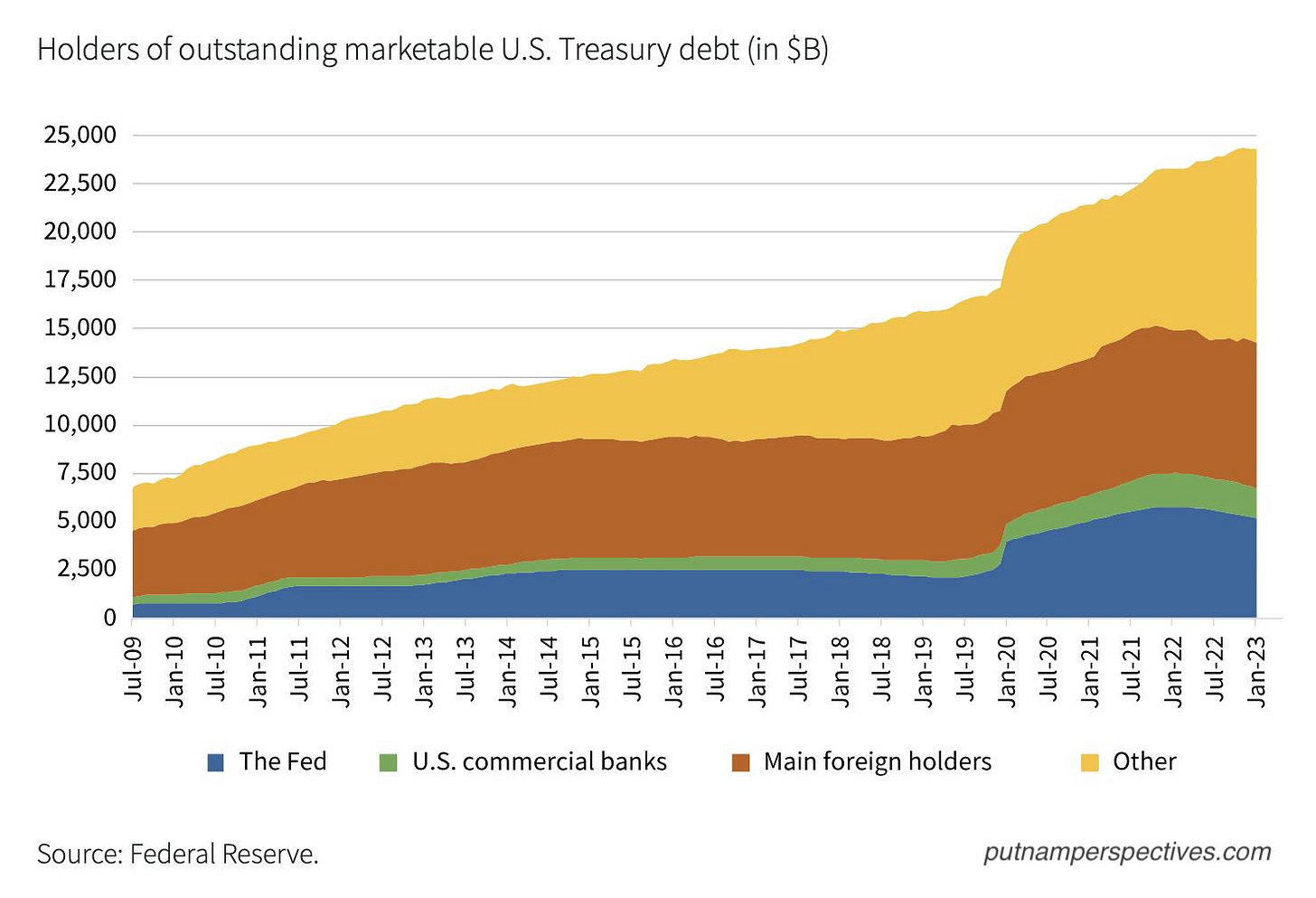

OK, OK, so who is buying all these bonds? I.e., who is lending the US all this money?

Well, let's have a look, shall we?

So, it is basically, you and me and others buying bonds directly in their IRAs, 401Ks, personal accounts, and indirectly through money market accounts (yellow area), US banks (green area), foreign central banks, i.e., Bank of Japan, Bank of China, etc. and other foreign buyers (brown area), and hold up, what's that blue area?

You got it.

The US Federal Reserve itself.

How do they possibly own all those US Treasuries, you ask?

Well, the money printer, of course.

Let me explain.

🫣 How Money is 'Printed'

If you have been following me, you know all about the Federal Reserve monetary tools QE and QT.

If not, or if you need a quick refresher, these stand for Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT).

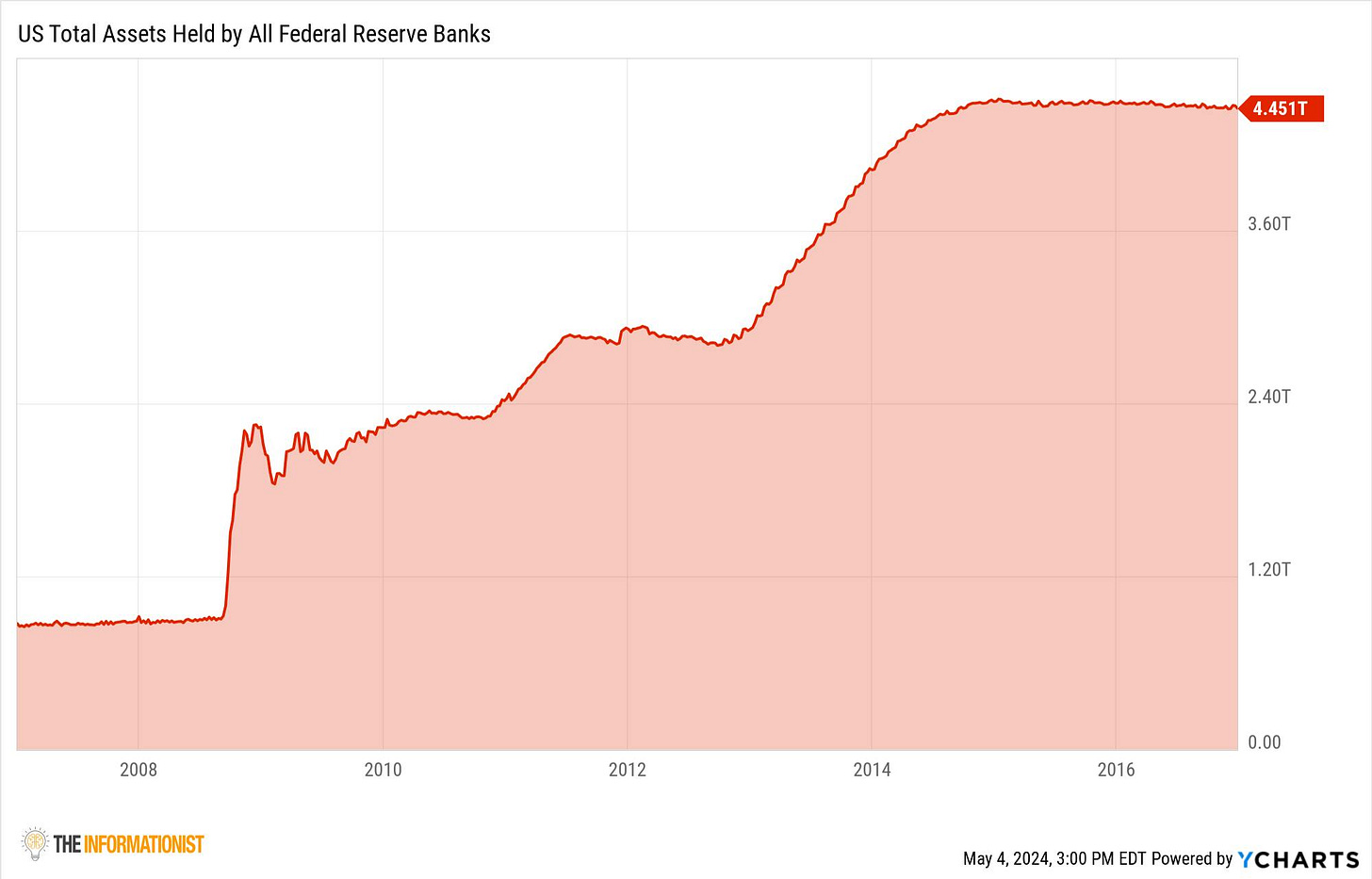

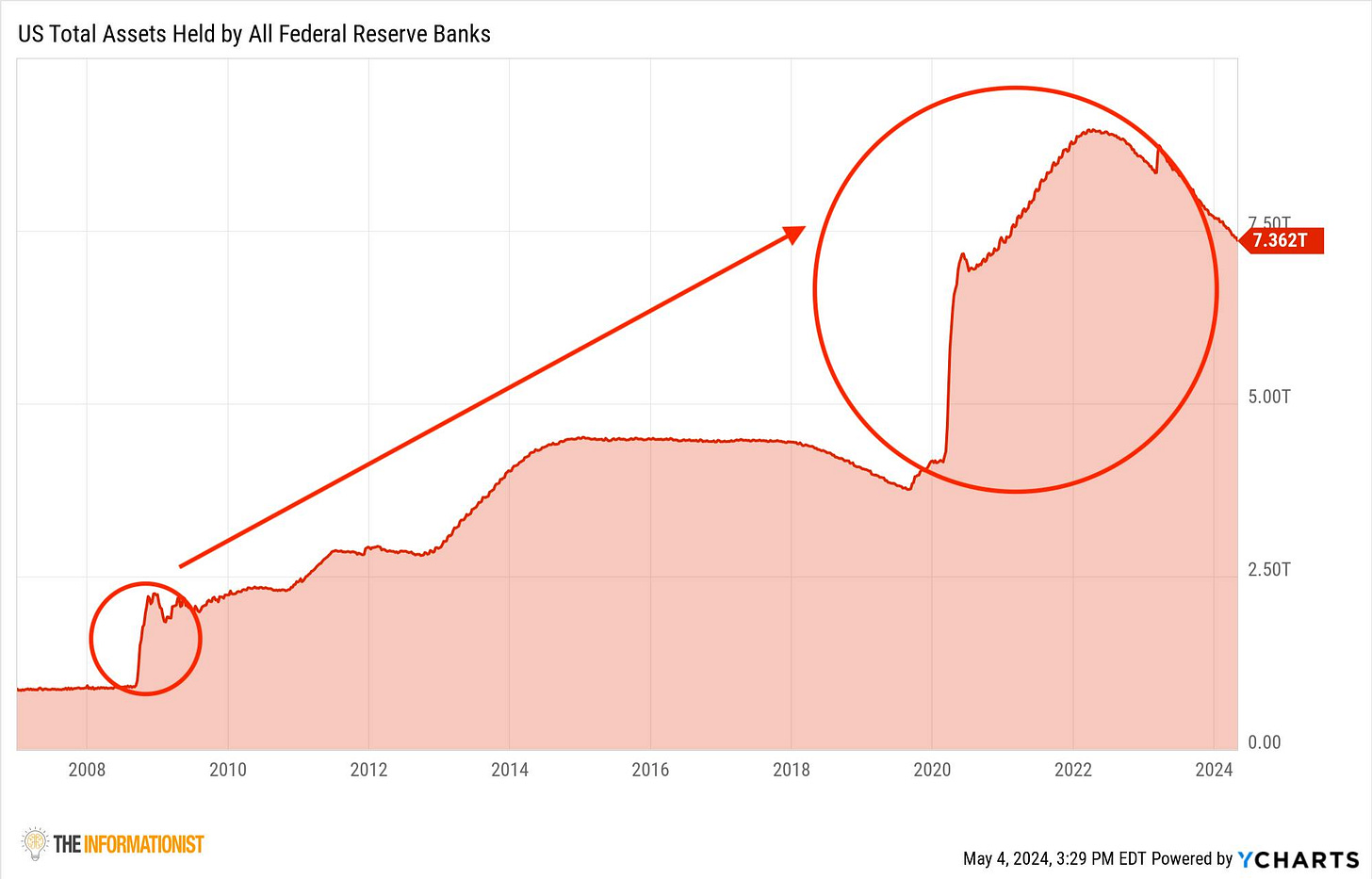

In periods of financial distress or recession, like the Great Financial Crisis, we saw the Fed use QE with a sort of shotgun approach, buying up US Treasuries and MBS (Mortgage Backed Securities) with what seemed like reckless abandon.

They bought over $1.5T of these assets over the course of a couple of years (and then kept adding for a few more years).

Flash forward to 2020 and the market distress of the lockdowns, and the Fed added a cash bazooka to its artillery.

That's a jump of over $5 Trillion in just 2 years. Look at the difference from 2009 to 2020.

*BAZOOKA BOOM*

But how did they do this?

Simple.

No, there is not an actual physical money printer spitting out bills (though I do like the Powell meme). 😅

In reality, it is a much less exciting and tangible function.

Basically, the Federal Reserve, as the US Central Bank, has the unique ability to create money. When the Fed decides to implement QE and purchase securities like US Treasury bonds, it does so by creating bank reserves out of thin air. This is a digital process of money creation.

Here's how it works:

The Fed announces its intention to purchase securities and the amount it intends to buy

Primary dealers (big intermediary banks) then buy these securities in the open market on behalf of the Fed

Once a purchase is made, the Fed credits the reserve accounts of the primary dealers with newly created money and puts the Treasuries on its own balance sheet

This crediting increases the total reserves of these banks, injecting liquidity directly into the banking system

Just press a button and Wham-o.

New money.

Imagine you are playing a game of monopoly where all the money has been distributed and is already in the game. Then a new player shows up to the game with a fist full of money from a Monopoly game from his house. And he just starts buying property left and right.

What has happened, is he has added new money to the game that was not there before.

He expanded the money supply.

And so, Park Place and Boardwalk just got way more expensive.

And this is effectively what the Fed is doing when it institutes QE and buys bonds in the open market. The Fed adds money to the markets that was not there before, injecting liquidity into those markets.

Look at how the M2 money supply (blue line) rises along with the expansion of the Fed's balance sheet.

And that, my friends, is classic money printing.

Nothing more and nothing less.

And now you know what a Treasury Bond is, who is buying them, and how the Fed 'money printer' actually works. Which means that you now know more than the Chief Economist to the White House.

A truly terrifying thought.

That's it for today. If you enjoy The Informationist and find it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️