💡 Why Can't You Get Ahead? (And How to Finally Fix It)

Issue 200

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

What Actually Happened in 1971?

The Mechanics of the Wage-Productivity Gap

Why This Won’t Fix Itself (The Math of Debasement)

Investment Implications (And What to Do About It)

Inspirational Tweet:

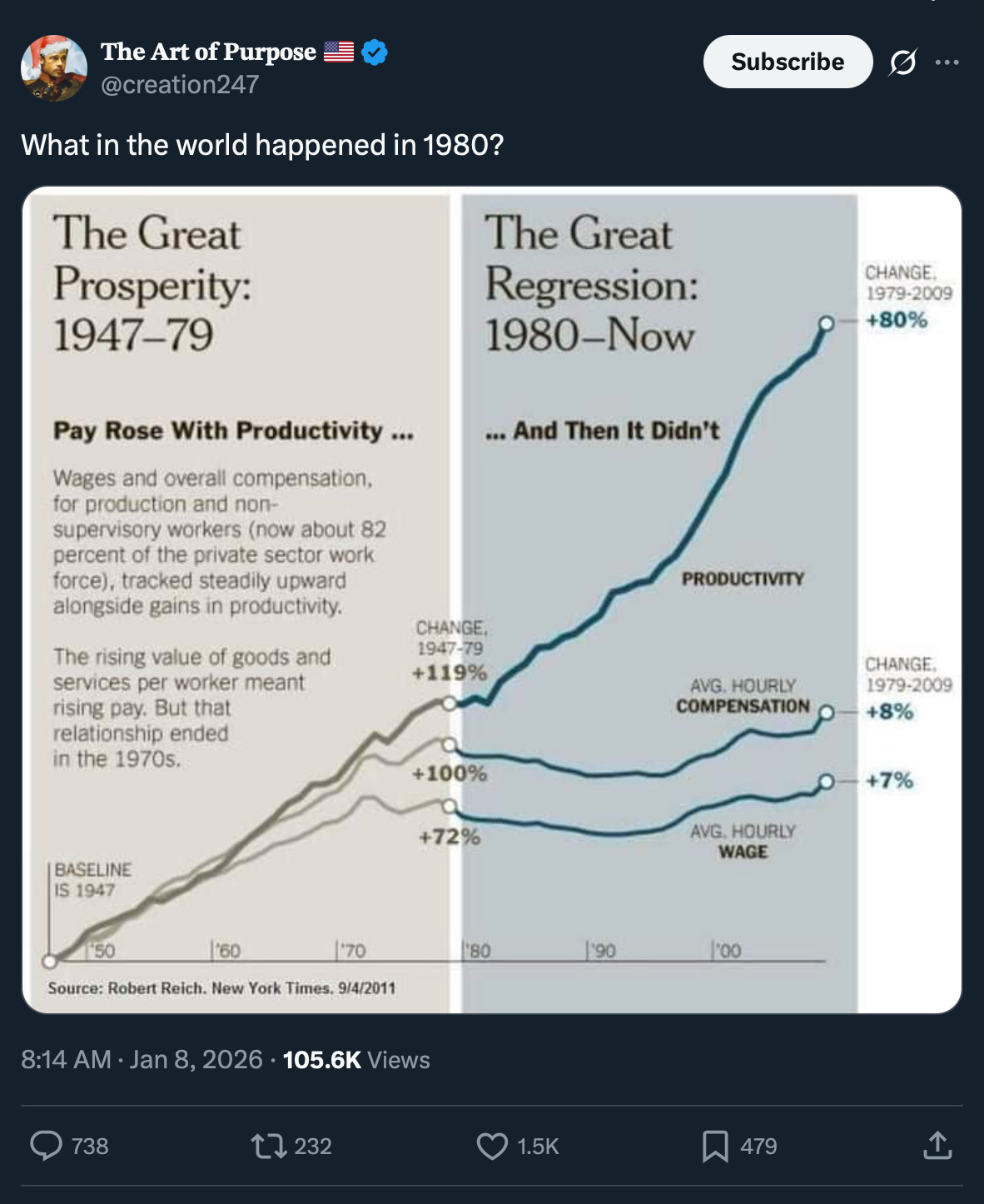

What in the world happened in 1980?

Good question, Art of Purpose. Good question.

But here’s the thing.

The chart shows productivity and wages diverging around 1980. But that’s just when the effects became visible. The cause happened nine years earlier.

On August 15, 1971, to be exact.

That’s the day President Nixon did something that would fundamentally reshape the relationship between work, money, and wealth for generations.

But what exactly did Nixon do? Why did it cause this divergence? And what does it mean for you and your money today?

All good questions, and ones we will answer, nice and easy as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a big cup of coffee, and settle into your favorite seat for a look at the moment that US money changed with this Sunday’s Informationist.

Partner Spot

Bitcoin Is the Greatest Asymmetry

As billions of people compete for a fixed supply of 21 million coins while fiat currency supplies continue to expand, bitcoin’s risk-reward profile stands apart. Last week, Parker Lewis joined Unchained for an online video premiere exploring the forces shaping bitcoin’s opportunity today and what current market and policy conditions may mean going forward.

In a recent talk at the Old Parkland debate chamber in Dallas, Parker covered:

Why bitcoin is fundamentally asymmetric, grounded in first principles

How probability—not short-term price—shapes the risk-reward profile

What current market conditions and Fed policy mean for bitcoin in 2026

If you want a clearer framework for thinking about bitcoin’s opportunity and the risks of overlooking it, this is the talk to share with friends and family.

The full session is online, free to attend:

🤑 What Actually Happened in 1971?

If you’ve been reading The Informationist for a while, you’ve heard me point to this date before. I’ve referenced it in discussions about the Cantillon Effect, currency debasement, and wealth inequality.

But we’ve never really gone deep on what actually happened that day and why it matters so much. So let’s do that today.

First, let’s look back up at that chart and what it is actually showing us.

From 1947 to about 1979, wages and productivity grew together. Workers produced more, and workers got paid more. Simple. Fair. Logical. The way it should work.

Then something changed.

From around 1980 and on, productivity kept climbing (up 80% through 2009), while wages pretty much flatlined (up just 8% in that same period). For some reason, American workers kept getting better at their jobs but they somehow stopped sharing in the gains.

So what happened?

To understand, we have to travel back to a sleepy Sunday evening in August, 1971. The night that President Richard Nixon interrupted regularly scheduled television programming to make an announcement.

The show he interrupted was Bonanza, of all things. Oh so poetic in so many ways.

President Nixon called it the “New Economic Policy.”

History would call it the “Nixon Shock.”

For those of you who have not been around these parts and heard me or others talk about it, here is what he did:

Nixon unilaterally ended the convertibility of the US dollar to gold.

Wait, what?

See, since 1944, under the Bretton Woods Agreement, the dollar was tied to gold at $35 per ounce. Other countries’ currencies were then tied to the US dollar.

So the dollar became the center of the system.

Not because every single dollar bill had a matching gold bar with its name on it, but because foreign governments could turn US dollars into US gold at that fixed price if they wanted to.

But then Nixon reneged on that agreement.

Imagine you go to Las Vegas and hit the Bellagio casino. You trade your dollars for chips, and you play. The whole system works because you trust that when you’re done, you can walk up to the cashier and trade those chips back for real money. The chips aren’t valuable in themselves. They’re valuable because of what they represent: a claim on something real.

That’s what the dollar was. A chip backed by gold.

It was a constraint. A limit. A tether to reality.

If the US wanted to spend far beyond its means, it could print dollars. But that created a massive risk that other countries could call its bluff and ask for gold instead. They could walk up to the cashier window. That threat helped keep the system honest.

Then the late 1960s hit.

The US was funding a massive war overseas at the same time it had big spending programs at home. Dollars flooded out into the world. Foreign governments started getting nervous.

France, led by Charles de Gaulle, kept going to the cashier window, exchanging their dollars for gold. Other countries quietly followed.

America’s gold stockpile started draining. Suddenly, too many players were cashing in their chips.

Nixon had a choice: cut spending dramatically, or break the link to gold.

Of course, he chose Option B.

On August 15, 1971, he closed the gold window. The cashier window slammed shut. No more gold for your dollars.

But here’s the thing: the chips didn’t disappear. The US just told the world, “You can’t redeem these for gold anymore. But don’t worry, they’re still good money! You can still use them to buy stuff.”

Somehow, the game kept going.

And we’ve all been playing with those chips ever since.

Just like that, with a stroke of a pen, the dollar went from being backed by gold to being backed by... well, nothing. Just the “full faith and credit” of the US government.

We all know what a crock that ‘full faith and credit’ is today.

The dollar has become what economists call “fiat” currency. Latin for “let it be.” Money by decree. Money because the government says so.

And just like that, the constraint was gone.

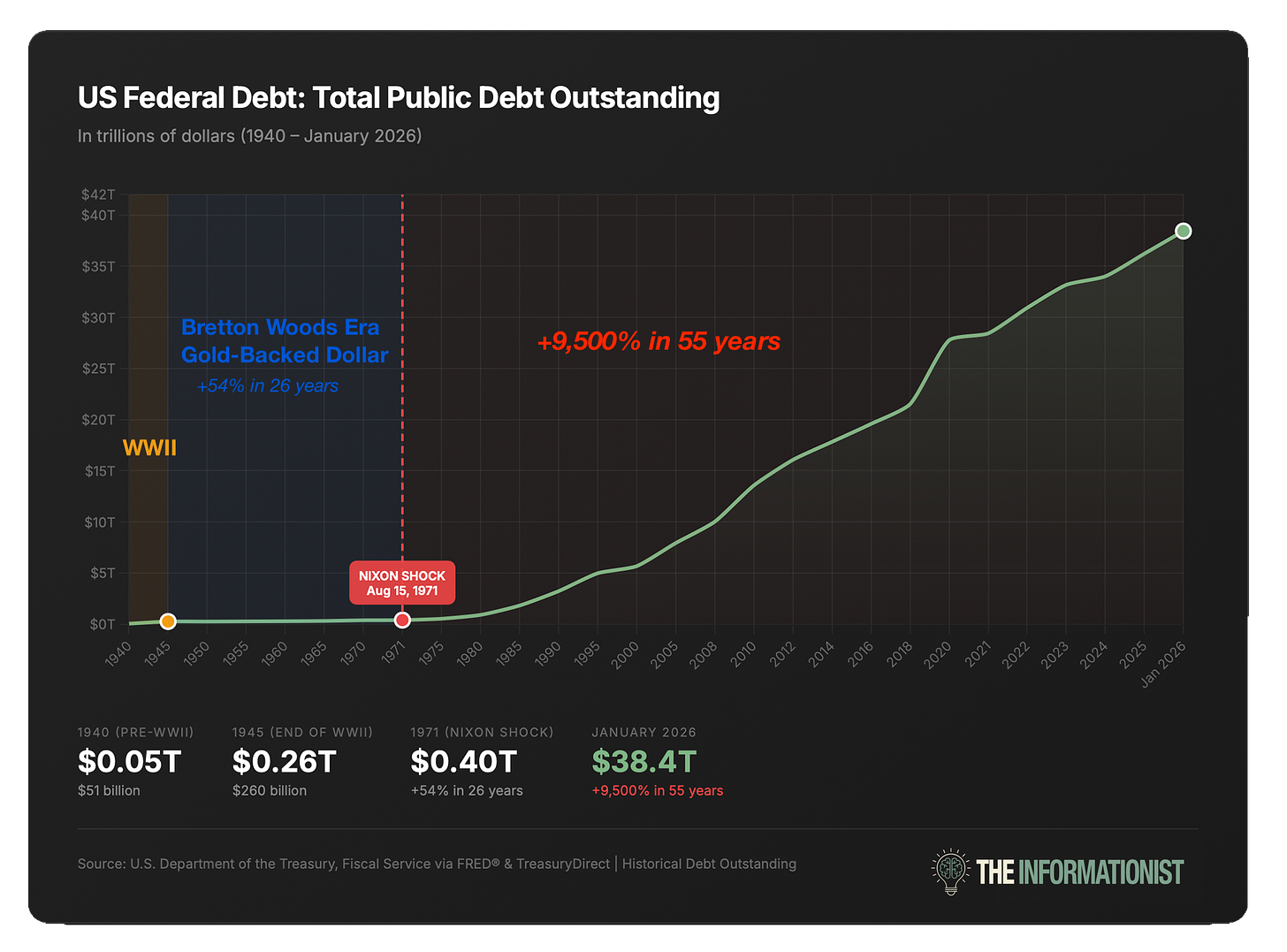

Look at this chart:

Before 1971, the US Debt line is relatively flat. Not perfect, but constrained. After 1971? Debt doubles in under a decade to $800 billion by 1980 and then launches like a rocket ship higher from there.

Why?

The government could now spend without limits. And spend it did.

But here’s what they don’t teach in schools: when you remove the constraint on money creation, you fundamentally change the relationship between work and wealth.

How, you ask?

Let’s walk through that next.

🔧 The Mechanics of the Wage-Productivity Gap

So the constraint was gone. The government could create money at will.

But here’s the question: if more money was flowing into the system, why didn’t wages keep up with productivity? Where did all that new money actually go?

The answer lies in something called the Cantillon Effect, named after an 18th-century Irish-French economist named Richard Cantillon.

And understanding it will change how you see everything.

FYI, I have written all about the Cantillon Effect before, and if you want to read a deeper dive on that, you can find it right here:

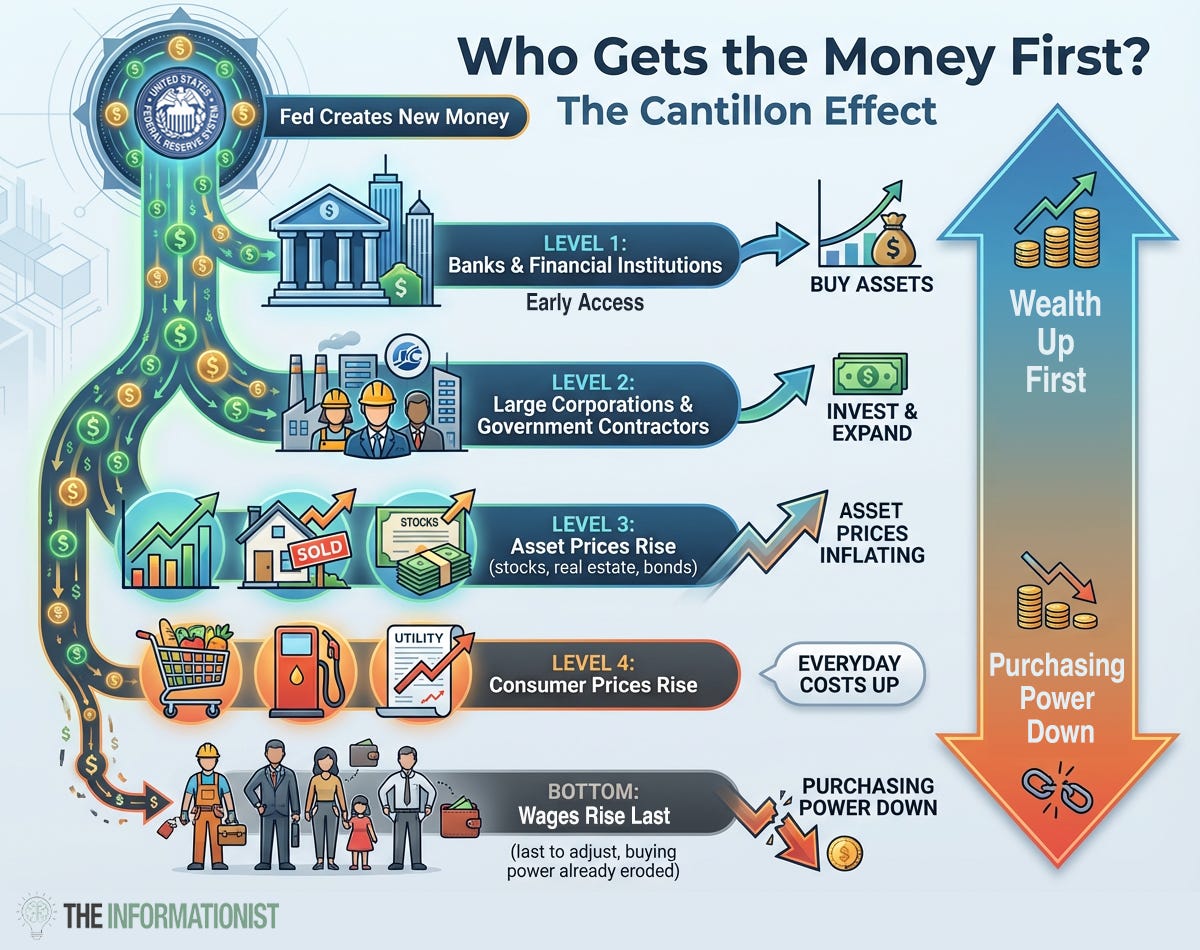

For the TL;DR crowd, the bottom line is this: when new money enters an economy, it doesn’t arrive evenly, like rain falling on everyone at once. It enters at specific points and flows outward from there.

Like water falling on a roof of a tall building, pooling in certain areas at the top, the penthouses, then collecting into drains that send it directly to specific collection tanks, and then whatever is still left over trickling off the sides of the building and winding all the way down to the street.

Unfortunately, this is pretty much how the Fed’s money printing system actually works.

Like so.

The Federal Reserve creates new money. But it doesn’t mail checks to every American. Instead, that money enters the economy through the banking system. Banks get it first. They lend it to large corporations, hedge funds, private equity firms, and government contractors. These players use it to buy assets: stocks, bonds, real estate, companies.

What happens next? Asset prices rise.

Only later, after some of the money has worked its way through the system, does it trickle into the broader economy. Businesses eventually raise wages. But by then, prices have already adjusted upward.

Take a moment and look at this visual:

Like the water pooling and collecting and being diverted until a small trickle is left to make its way to street level, the rain of new money is the same.

Those closest to the money spigot (banks, financial institutions, large corporations) get to spend new dollars before prices adjust. They buy assets and then the prices rise. As a result, their wealth increases.

Those furthest from the spigot (wage earners, savers, retirees on fixed incomes) get the new money last, if at all. By the time it reaches them, prices have already risen. Their purchasing power has decreased.

Same new dollar. Opposite outcomes. (And while it’s not the only factor, it’s a big one.)

This helps explain why productivity and wages diverged after 1971.

Workers kept producing more. But the gains from that productivity flowed to asset owners more than wage earners. New money created by a now-unconstrained Fed inflated stock prices, real estate values, and bond portfolios. It made the rich richer.

Meanwhile, wages stagnated in real terms (adjusted for inflation). The average worker’s paycheck might have grown in nominal dollars, but their purchasing power barely budged. Housing got more expensive. Healthcare got more expensive. Education got more expensive. And eventually everything, including insurance and groceries, too.

The productivity gains were real. But the wage gains lagged so severely, they were almost an illusion.

And here’s the hardest part: It’s a well known and unfortunate outcome of how the system works, but there is no incentive to change it.

New money doesn’t enter evenly. It enters through specific channels. And that creates winners and losers over time.

But why won’t they just fix the problem? Make it fair for everyone?

Well, the problem is not just the system itself, the problem is now math.

📉 Why This Won’t Fix Itself

At this point, you might be thinking: Okay, I get it. The system is tilted. But couldn’t the government just... stop? Couldn’t they balance the budget, pay down the debt, and return to some kind of fiscal sanity?

I used to wonder the same thing.

Then I watched the last 30 years of American politics.

The US federal government currently has over $38 trillion in debt. That’s roughly $114,000 for every man, woman, and child in America. More than 130% of GDP. The interest payments alone now exceed $1 trillion per year, more than we spend on defense.

And it’s accelerating. We’re adding north of $2 trillion to the debt every single year. Not paying it down. Adding to it.

Now here’s where it gets fun.

Just this week, President Trump proposed increasing the defense budget to $1.5 trillion for 2027. That’s up from $901 billion in 2026. A 67% increase. In one year. To build a “Dream Military.”

Meanwhile, the House just passed a bill to extend Obamacare subsidies for three more years, with 17 Republicans crossing the aisle to vote with Democrats. The Senate says it’s dead on arrival, but the pressure is on. Neither party wants to be blamed when premiums double.

You know what neither party is proposing?

Spending less.

Republicans want to spend on defense and tax cuts. Democrats want to spend on healthcare and social programs. Both will tell you with a straight face that their spending is essential and the other side’s is reckless. Both will add trillions to the debt without blinking.

This isn’t a partisan observation. It’s just math.

In my lifetime, we’ve had Republican presidents, Democratic presidents, split congresses, unified congresses, budget deals, sequesters, debt ceiling showdowns, government shutdowns, and approximately ten thousand politicians promising fiscal responsibility.

The debt went from $1 trillion to $38 trillion.

And here’s the part that most people miss. It’s not just the debt. It’s the money itself.

In August 1971, when Nixon closed the gold window, the total M2 money supply in the United States was about $710 billion. That’s all the money in circulation: cash, checking accounts, savings deposits, everything.

Today? M2 sits at $22.3 trillion.

That’s a 31x increase. Over 3,000% more dollars sloshing around the system than before the constraint was removed.

Look at that curve. Especially what happened in 2020. The Fed printed nearly $5 trillion in two years. They called it "emergency measures." Problem is, the emergency is long over, yet the money is still here.

Now think about what this means for your savings.

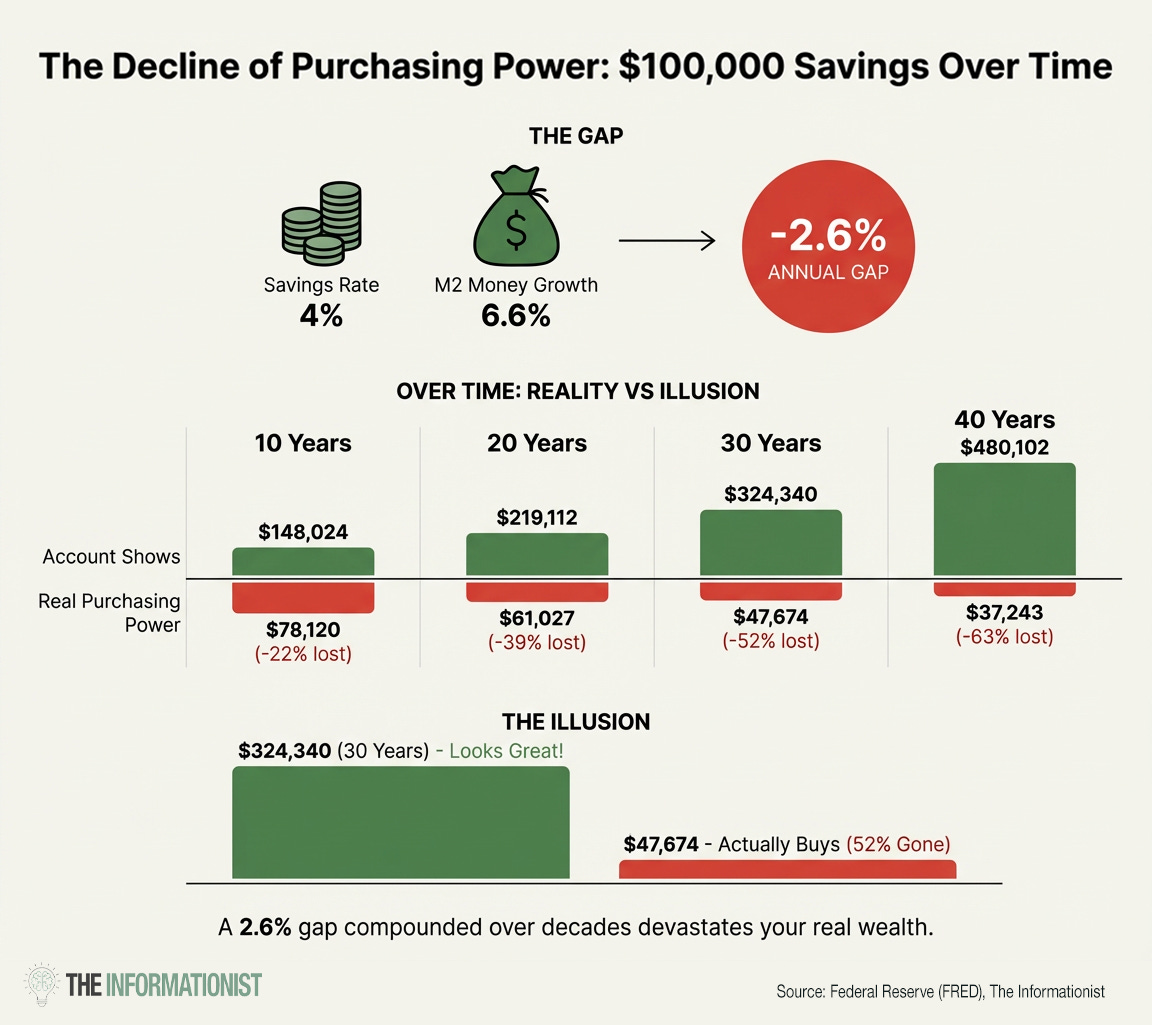

The M2 money supply has grown at roughly 6.6% annually since 1971. Your savings account? About 4% if you’re lucky. Maybe 5% in a high-yield account.

You’re not keeping up. You’re falling behind. Every year.

This is why the price of everything feels like it keeps getting further out of reach. It’s not that houses and healthcare and education got 31 times better. It’s that there are 31 times more dollars chasing them.

About the math and incentives, the US has a few limited options:

Option 1: Austerity. Slash spending. Raise taxes. Run budget surpluses for decades. Pay down the debt the old-fashioned way.

This would require cutting Social Security, Medicare, defense, and virtually every government program simultaneously while raising taxes on everyone. It would be brutally painful. It would cause a severe recession. And it would require politicians to tell voters they’re getting less while paying more.

When one party wants $1.5 trillion for defense and the other is fighting for endless healthcare subsidies? When the debt ceiling debate becomes a hostage negotiation every two years?

Yeah, not happening.

Option 2: Raise Taxes. This is the one that sounds reasonable until you do the math.

The federal government currently collects about $5 trillion per year in revenue. We’re running deficits of $2 trillion or more. To close that gap through taxes alone, you’d need to increase revenue by 40%.

But here’s the problem: when you raise taxes significantly, you don’t just collect more money. You change behavior. Businesses invest less. Entrepreneurs take fewer risks. Capital flows to lower-tax jurisdictions. High earners restructure, relocate, or retire early. The tax base itself shrinks.

This isn’t theory. France tried a 75% top tax rate in 2012. The result? Wealthy citizens fled to Belgium and Switzerland, revenues disappointed, and they abandoned it within two years.

And we’re watching it happen in real time right here at home.

California and New York are experiencing capital flight just from the threat of new tax policies. Hedge funds are relocating to Florida and Texas. Tech founders are moving to Miami and Austin. High-net-worth individuals are restructuring their residency before the tax bills even pass. The mere possibility of higher taxes is enough to send productive capital running for the exits.

These aren’t hypotheticals. These are moving trucks.

And even if you could squeeze more revenue out of the economy without killing productivity, you’d still need Congress to agree on who pays. Tax the rich? They have lobbyists, accountants, and private jets to Florida. Tax corporations? They pass it to consumers or move headquarters offshore. Tax the middle class? Good luck winning reelection.

The reality is that federal tax revenue has averaged around 17-18% of GDP for decades, regardless of the top marginal rate. Whether the top rate was 90% in the 1950s or 37% today, the government collects roughly the same share of the economy. It’s called Hauser’s Law, and it suggests there’s a natural ceiling to how much you can extract through taxation.

So even in the best case, raising taxes might nibble at the edges of the deficit. It won’t solve a $2 trillion annual hole. And it certainly won’t touch $38 trillion in accumulated debt.

Not happening.

Option 3: Default. The US government simply refuses to pay its debts. Treasury bonds become worthless. The dollar collapses. Global financial system implodes. Every pension fund, bank, and foreign government holding US debt gets wiped out. Civilization-ending stuff.

Definitely not happening.

Option 4: Debasement (aka the Soft Default). Create new money to service the old debts. Let inflation quietly shrink the real value of what you owe. The debt stays the same in nominal terms, but the dollars it’s denominated in become worth less and less.

This is the only option that doesn’t require political courage.

This is the only option that doesn’t show up clearly on anyone’s bill.

This is the only option that lets politicians keep spending while appearing to “manage” the debt.

Which option do you think they’ll choose?

They’ll print. They always print. They have to print.

This isn’t cynicism. It’s a reinforcing pattern.

Every major economy in history that has wound itself into this position has eventually chosen debasement. Not because they wanted to. Because it was the only door that wasn’t barricaded shut.

The Fed will insist that they’re committed to price stability. They’ll raise rates and publicly condemn inflation. And when the next crisis hits (and it will), they’ll print trillions more. They did it in 2008. They did it in 2020. They’ll do it again.

It’s not a conspiracy. It’s an incentive structure. The people making these decisions don’t suffer the consequences. They own assets. They’re on the right side of the Cantillon Effect. They’ll be fine.

The question is: will you?

Because here’s what happens if you do nothing.

If you keep your savings in dollars, in a bank account earning 2, 3 or even 4% while the money supply grows at 6.6%, you’re losing ground every year. Not dramatically. Not in a way that shows up on a statement. Just slowly, invisibly, like a leak you don’t notice until the basement is flooded.

Here’s an illustration of the effects of a 2.6% gap between interest on savings and money expansion:

The result of compounding that effect over decades is simply devastating.

As for the wage-productivity gap we started with…

That’s not mere history to be studied. It’s still happening. It’s happening to you right now. Every year your paycheck buys a little less house, a little less education, a little less healthcare, a little less retirement.

And it is not an accident. That’s the system working as designed.

💰 What the Wealthy Already Know

Here’s something that honestly took me years to understand. Even being on Wall Street and in the ,middle of the money making machine.

I cut myself some slack because my parents (who were from extremely poor neighborhoods in NYC) never talked about money or investing. They were not taught about the system themselves. And so, it took me a few years being around all those people, who were taught it (by their wealthy parents and friends) and did understand the game, to catch up.

In hindsight, the lesson was so simple: Rich people don’t get rich by earning more dollars. They get rich by owning things that go up when dollars go down.

Read that again.

This is the secret hiding in plain sight. The wealthy don’t save in cash. They save in assets. Stocks, real estate, businesses, land, gold. Anything that absorbs the new money rather than being diluted by it.

They’re not smarter than you. They just understand the game.

When the Fed prints, asset prices rise. When asset prices rise, owners get richer. When owners get richer relative to workers, the gap widens. It’s not complicated. It’s just not taught.

If you’ve been reading The Informationist for a while, you’ve heard me talk about this before. I’ve written about the debasement trade. I’ve quoted Ray Dalio’s “cash is trash” thesis more times than I can count. I’ve pounded the table on gold, on Bitcoin, on positioning for what’s coming.

So, I’m not going to repeat all of that today.

But I do want to say something about this particular moment, because I think it matters.

Right now, gold is trading at all-time highs of $4,500 and silver has ripped to the nosebleed level of $80 per ounce. Central banks around the world are accumulating gold at a pace we haven’t seen in decades. The market is telling you something.

Meanwhile, Bitcoin is lagging. The Magnificent 7 tech stocks are hovering at all-time highs. And the Fed is signaling uncertainty about rate cuts in 2026.

What do you do with that?

Here’s my honest answer: I don’t know exactly what happens next. Neither does anyone else.

Maybe the stock market corrects 20% this year and drags Bitcoin down with it. Maybe inflation spikes again and the Fed reverses course. Maybe we get a soft landing and everything grinds higher.

I’ve been doing this for over 30 years, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that short-term predictions are a fool’s game.

But here’s what I do know.

The debt isn’t going away. The deficits aren’t shrinking. The incentives haven’t changed. Whether it’s this year or next year or five years from now, the trajectory is the same: more money creation, more debasement, more wealth transfer from savers to owners.

That’s not a prediction. It’s simple arithmetic.

So I don’t try to time it. I position for it.

I own gold because it’s been a store of value for 5,000 years and central banks are buying it hand over fist. I own Bitcoin because it’s the first digitally scarce asset in history, and over the long arc, it has tracked money supply expansion almost perfectly. I own real estate because property absorbs inflation and generates income in depreciating dollars. I own equities because businesses reprice their goods and services as the currency weakens.

Do these assets go down sometimes? Absolutely. Bitcoin could drop 40% tomorrow in a risk-off selloff. Gold and silver can and likely will be volatile. Real estate is illiquid. None of this is a straight line.

But that’s exactly why this is about discipline, not prediction.

The point isn’t to catch every move. The point is to be positioned correctly for the long game. To own things that benefit from debasement rather than being destroyed by it. To stop thinking like a saver and start thinking like an owner.

Dalio calls it the “beautiful deleveraging” (when it works) or the “ugly deleveraging” (when it doesn’t). Either way, the playbook is the same: you don’t want to be holding the currency. You want to be holding the assets.

I don’t know what the Fed will do this year. I don’t know if Trump’s $1.5 trillion defense budget passes or if the ACA subsidies get extended or if we have another debt ceiling crisis. I don’t know which party will control Congress after the midterms.

But I know the direction.

More debt. More deficits. More printing. More debasement.

So, let me bring this full circle.

We started with a simple question: what happened in 1971?

Now you know.

Nixon severed the dollar’s link to gold, removing the constraint on money creation. The government and Fed gained the ability to print without limit. That new money flowed to asset owners first, inflating their wealth, while wages stagnated in real terms. The productivity gains were real. The wage gains were an illusion.

This wasn’t a bug. It was a feature. And it’s still running.

The gap between productivity and wages isn’t closing. The debt isn’t shrinking. The printing isn’t stopping. Gold at $4,500 tells you everything you need to know about what the market thinks is coming.

You can be angry about this. I was, for a long time. But anger doesn’t pay the bills. Understanding does.

So take what you’ve learned today. Look at your own balance sheet. Ask yourself: am I positioned like an owner, or like someone hoping the system will be fair?

Because the system isn’t fair. It never was.

But now you know the rules.

And now you can play the system, too.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little smarter knowing what happened in 1971 and why it still matters today.

If this piece helped you see things differently, share it with someone you care about. A friend, a family member, a coworker who’s frustrated that they’re working harder and falling behind. Sometimes the most valuable thing you can give someone is clarity.

And as always, feel free to hit reply and let me know what you think.

Talk soon.

James ✌️

Great stuff James. Should be taught in schools.

Love the new graphics