💡 When Will The Fed *Fully* Pivot?

Issue 131

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

QT vs QE

Current Fed Stance

When End QT?

When Cowbell?

Inspirational Note (*from Nostr):

Now that the Fed has all but declared that the fight against inflation is over, many investors have begun to turn to the next question:

When will the Fed stop selling assets off its own balance sheet?

They ask this question because the Fed selling these assets is known as quantitative tightening, and this is a form of removing liquidity from markets.

The opposite of easing, it somewhat counteracts the effects of the Fed lowering interest rates.

So, why would they continue this QT, when—oh when—will they stop? And, of course, why should you care?

Good and important questions, and ones we will answer, nice and easy as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a nice big cup of coffee and settle into a comfortable chair for a graphic-heavy issue of this Sunday’s Informationist.

🤨 QT vs QE

First things first, and really quickly, let’s review QE and QT.

As you may recall, the Fed has two main tools in its money manipulation toolbox. One is raising and lowering interest rates, and the other is buying and selling assets in the open market.

Raising and lowering interest rates affects the cost of capital for individuals and businesses and can affect the amount of leverage and liquidity in the system.

Higher rates tend to slow the economy down and vice versa.

And the Fed buying and selling assets in the open market will either add liquidity to, or remove it from, the system.

When the Fed buys assets, such as US Treasuries or mortgage backed securities (MBOs) in the open market, this is known as quantitative easing (QE) and it adds liquidity—or money—to the overall financial system that was not there before.

And conversely, when the Fed sells assets, those same US Treasuries or MBOs that it previously bought in the open market, this is known as quantitative tightening (QT) and it removes liquidity from the overall financial system.

Remember, the massive splash of liquidity that the Fed added to the markets in the Great Quantitative Easing of 2020 was so powerful that it created massive inflation that the Fed has been dealing with ever since.

And so, they have been trying to peel some of those assets off their balance sheet methodically over the last two years through QT.

We’ll get to just how much they have been able to sell and how successful the QT has been in a minute.

But let’s review the Fed’s current stance.

🧐 Current Fed Stance

As we said, lots of chatter and high expectations now for the Fed to start lowering interest rates, starting on September 18th.

And why not? Inflation is way down from its peak of 9.1%, right?

I mean, job well done, let’s crack open the bubbly and caviar.

Just look at the chart.

Wait, you may be saying, that chart shows the latest readings of 2.6% and 2.9%, that’s not 2%!

You would be correct. And so, it seems that the Fed has decided that the progress toward 2% is significant enough to declare victory.

Close enough for government work, anyway.

I mean, Chairman Powell as much as said so in his last appearance, during the Fed’s annual economic policy symposium. You know, the one that takes place in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, with the snow dusted Teton peaks in the background.

What a life for these appointed officials, eh? Champagne and caviar, indeed.

In any case, he said, “After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.”

Powell, the inflation slayer.

Of course, his comments then immediately turned to unemployment, as he said, “Today, the labor market has cooled considerably from its formerly overheated state.”

and…

“The upside risks to inflation have diminished. And the downside risks to employment have increased.”

and finally,

“The time has come for policy to adjust.”

*Boom* The Powell Pivot is on.

Partial pivot, that is…but what is he seeing that has him spooked on the labor market?

First, we had a pretty dismal last reading of the unemployment rate. At 4.3%, and rising, Powell is now concerned that the rate begins to spike, as we have seen in past recessions.

And his concern, a small one right now, will grown exponentially once the rate jumps over 5% (red dotted line).

Part of the reason for this is the measure of unemployment acceleration, known as the Sahm Rule. Once this is tripped, we are headed into or already in a recession. And we just tripped it, as many of you who follow me already know.

You can see here that (as the rule states), the rate (calculated as an average of the last 3 months) has risen more than .5% from the lowest point in the last year.

Sahm Rule tripped. Recession imminent?

Finally, we had a huge revision to the jobs created number, which took the original estimated number (already revised lower once) down from 2.9 million jobs created in 2024 to 2.1 million. A 28% revision lower. 😨

Perfect timing, as Powell was given this data the day before the Jackson Hole boondogg—er, I mean, symposium, giving Powell plenty of air cover for talks of a September cut.

And so, we are all but assured at least a 25bp cut in a few weeks. But what are the odds we get a larger cut, like 50bps, and when will the Fed stop the QT side of the money manipulation policy?

🤔 When End QT?

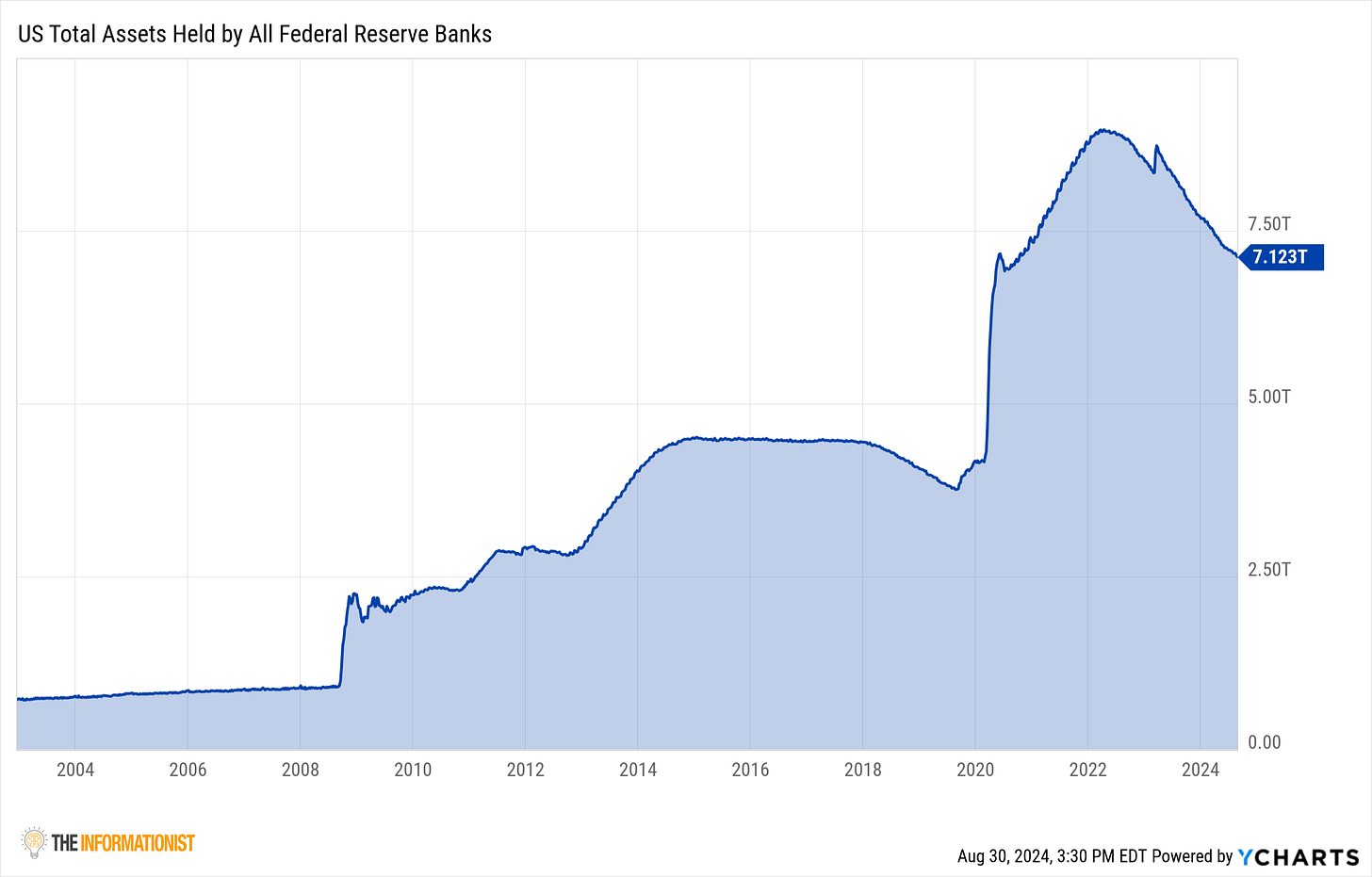

Thing is, after adding just under $5 trillion to their balance sheet, the Fed has struggled to peel this off over the last two years.

It’s only sold $1.8 trillion worth and still has over $7.1 trillion on its balance sheet.

And just last meeting, the rate at which the Fed has been letting these bonds run off the sheets (i.e., expire without replacing them) was reduced from $60 billion per month to a mere $25 billion per month.

It would take 24 years at that rate to get back to zero.

So, what are they going to do?