💡 US Debt Downgraded Again: Are Treasuries Becoming Junk?

Issue 166

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

Credit Ratings Simplified

A Fistful of Debt History

Moody’s: The Last Believer

CDS Check: Are US Bonds Headed for Default?

Inspirational Tweet:

Well, well, well. There it is. The last ratings agency to do so, Moody’s has downgraded US Debt, removing the Treasury’s final claim to AAA-status.

Ouch.

But truly, is anyone surprised?

Like Kobeissi points out above, US financial metrics have been consistently sliding, weakening US Treasuries’ status.

But what does this all really mean? Will anyone care? Will it impact potential buyers?

And are US Treasuries headed for Junk status?

Fair questions, and ones we will answer (along with many more), quickly and easily as always.

So pour yourself a nice big cup of coffee, and settle into your favorite seat for a peek into Sovereign Debt credit ratings with this Sunday’s Informationist.

🤓 Credit Ratings Simplified

If you’ve been following me on Twitter/X or reading The Informationist for a while, you likely know most of this. But for those of you who are new around here, let’s take a moment to quickly review exactly what a bond rating is and what it means.

In the simplest terms, a credit rating is a risk score—i.e., measures of how likely a borrower is to repay its debt on time and in full.

That borrower might be a person applying for a car loan, a company asking for a bank loan…or a nation issuing trillions in Treasury bonds. The concept is the same for each of them.

A poor credit score can negatively impact your ability to borrow money, i.e., get a car loan, mortgage, or a credit card.

Companies face a similar challenge, in that a poor rating can affect their ability to issue bonds (borrow money) at attractive rates to maximize profits (or sometimes, to just keep operating).

higher credit = lower perceived risk = lower borrowing cost.

For individuals, we have the FICO score, as determined by Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion. For companies and governments, we have credit ratings issued by three primary credit rating agencies:

S&P Global Ratings

Moody’s Investors Service

Fitch Ratings

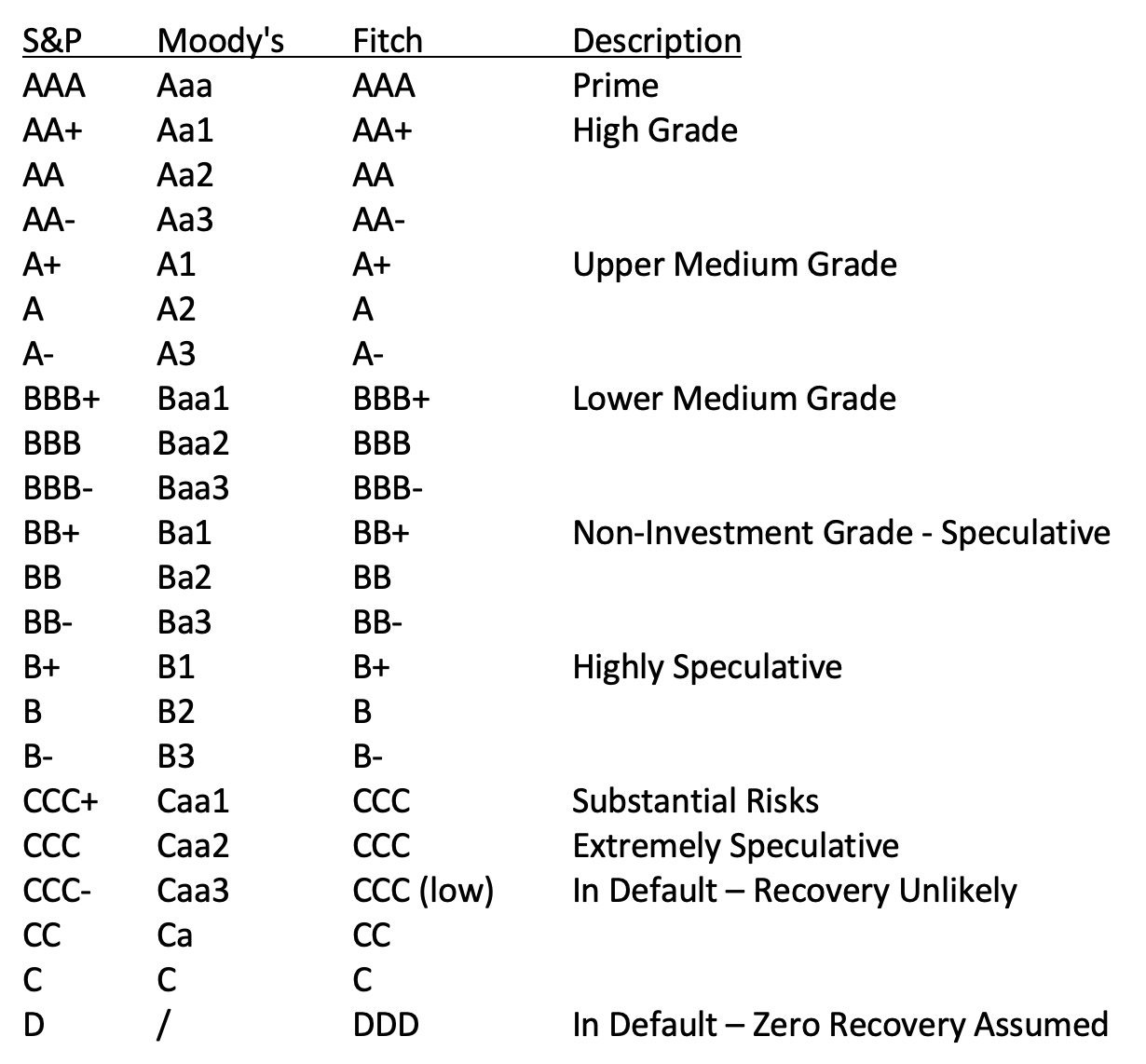

Each one assigns ratings on its own letter-based scale, but they broadly align. At the top of each scale is a designation like AAA (S&P/Fitch) or Aaa (Moody’s), meaning “essentially no risk.” As ratings fall, so does perceived creditworthiness — until you hit the “junk” zone.

The two most important categories above are:

Investment Grade: AAA down to BBB- (or Aaa to Baa3 for Moody’s)

Speculative (Junk): BB+ and below (or Ba1 and below)

And this distinction matters. A lot.

Why?

Many pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance companies are prohibited from holding non-investment grade bonds. So, a downgrade below that line can cause a re-balancing to lower exposure and risk and can even trigger forced selling.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, though, let’s be clear: The US is still far from that line.

That said, once you start slipping, the slope gets steeper.

And now you may be asking, how the heck do these agencies determine a credit rating for a country?

The answer is, credit rating determinations are intricate and complicated, and the formulas used by the agencies can be quite different for various entities and companies being rated.

For instance, a bank rating may rely heavily on debt to equity ratios, book values, and quality of deposits, while a technology company rating may focus on book to sales ratios and inventory turns.

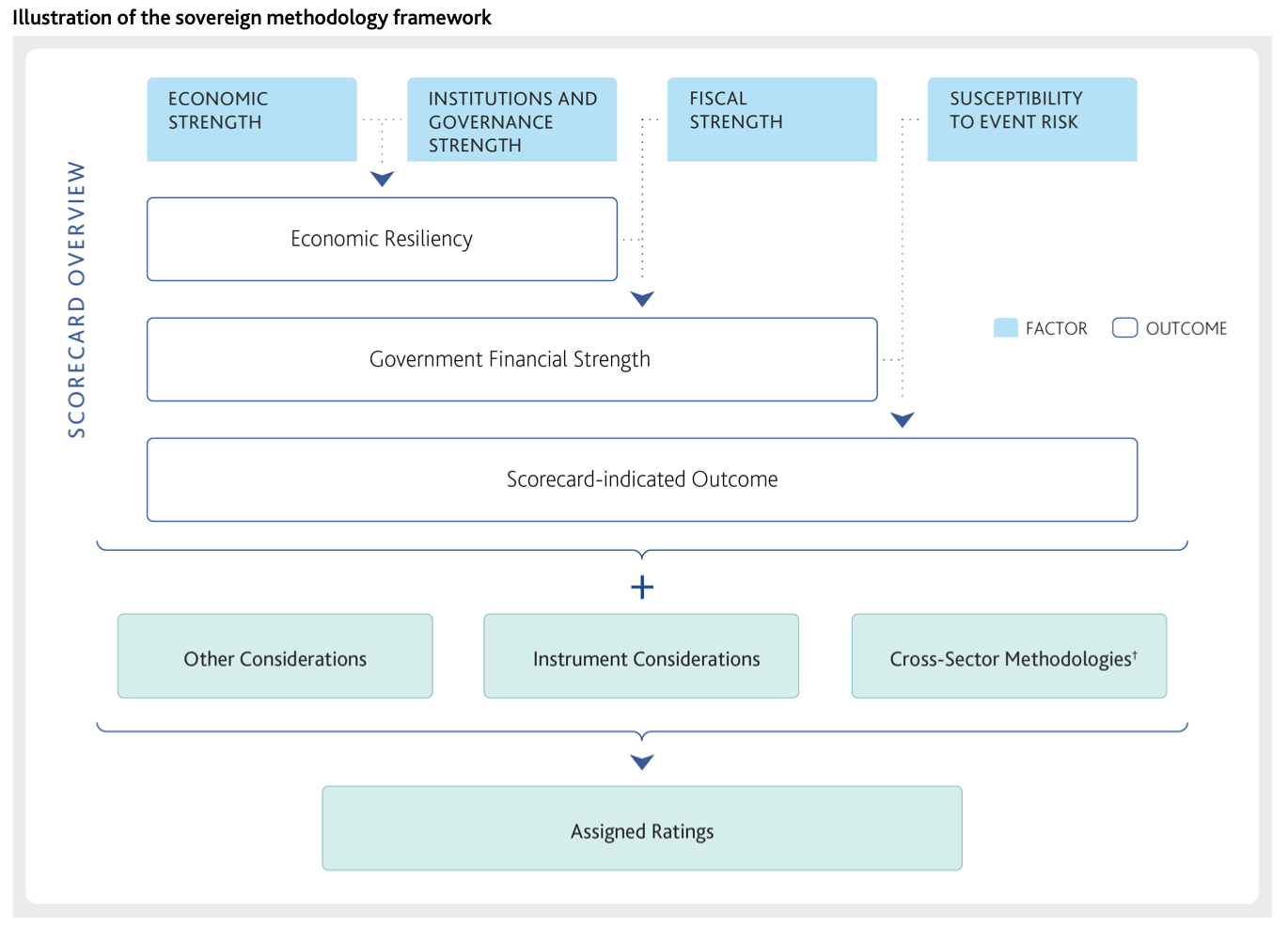

As you can imagine, the process for sovereigns is bit more subjective. For instance, here’s a table showing the process Moody’s uses to rate sovereign debt:

What do we see?

Moody’s sovereign credit ratings are driven by four main factors:

Economic Strength

Institutions and Governance Strength

Fiscal Strength

Susceptibility to Event Risk

These inputs feed into two key outcomes:

Economic Resiliency (based on economic and institutional strength)

Government Financial Strength (based on fiscal metrics and risk exposure)

The result is a scorecard-indicated outcome, which Moody’s then adjusts using subjective analysis before assigning a sovereign rating that reflects Moody’s holistic view of a nation’s creditworthiness.

Nothing like a bit of subjectiveness in scoring, you know, giving a grade on ‘feels’ or a ‘vibe’.

Problem is, these letters can matter.

A lot.

They often make the difference between the ability for a company (or country) to issue debt at a rate that is sustainable for that entity’s income and balance sheet.

Getting back to the US here, let’s see where Treasury ratings have been and then perhaps where they are headed from here.

✊ A Fistful of Debt History

It’s no secret that the US has long been considered one of the world's most creditworthy countries, with top ratings from the major agencies. In fact, the US enjoyed a Prime rating from all three agencies throughout the 20th and into the 21st century.

This changed, however, after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, when massive money printing and debt expansion caused increased scrutiny of national economies and the sheer amount if debt they were issuing.

Miraculously, the US still maintained its AAA rating.

(remember that subjective component to the ratings? 🤡)

And the US hung onto its AAA-rating by a thread, right up until the 2011 debt ceiling crisis.

See, per usual, federal debt had been approaching the ceiling, although in 2011, that ceiling was just $14.3 trillion.

Let’s take a peek at what happened and just how far we have come since then (😱):