The US Twin Deficit Syndrome

Issue 86

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox:

Today's Bullets:

What are the Twin Deficits?

Twin Deficit Hypothesis

A Third Deficit?

What's Ahead

Inspirational Tweet:

We've been hearing a lot about the bond market lately, particularly how yields are risingdespite the Fed futures falling (showing expectations of the Fed lowering rates next year). Just last week, The Informationist newsletter was all about Bond Vigilantes.

You know, the ones who have wrested control of the bond market from the Fed.

But what does this have to do with Twin Deficits?

I mean, what exactly are these deficits, and why do they even matter?

If these questions make your eyes glaze over in confusion, then you're about startle awake. Because we're going to unpack the Twin Deficit Hypothesis for you, nice and easy as always, today. In terms you will understand and may just frighten you.

So, grab your favorite mug of coffee, and settle in for a Sunday reckoning with The Informationist.

👥 What are the Twin Deficits?

First things first, what the heck are these Twin Deficits we're talking about?

Well, the first deficit may be obvious to you, especially if you've been following me for a while. This has to do with fiscal policy. I.e., government spending.

And if you have been following me, you know all about how the US runs large, perpetual deficits, and this policy has thrust us into what is called a debt spiral.

If you have somehow escaped this idea, I wrote all about it over a year ago, and you can find that here:

The long and short of it, and what we are focused on here today, is the part about spending. We spend way more than we make (produce).

The fiscal deficit.

The second deficit we're talking about is all about the balance of trade and payments.

Our Current Account.

There are two main components of the current account. The trade balance is imports vs exports and the balance of payments is income on foreign investments vs payments to foreigners on UST investments.

Let's first look at the trade balance.

A positive trade balance indicates a trade surplus (exports > imports), while a negative trade balance indicates a trade deficit (exports < imports).

When a country's imports increase, it's spending more on foreign goods and services.

This can be due to a stronger currency, strengthening economy, or perhaps domestic production not meeting demand (think: energy).

When a country's exports decrease, it means the country is not earning as much from its overseas sales.

This could be due to less competitive prices (think: stronger currency), or lower demand for the country's goods/services abroad (think: energy agreements elsewhere).

And so, put simply, if total imports exceed total exports, it is called a trade deficit.

Taking that one step further, we then add in the balance of income vs payments abroad. For instance, when a country pays more in interest on its own bonds than it receives from owning foreign bonds, this creates a negative balance of payments.

And so, bringing it all together, we add up the trade balance and the balance of payments to determine if a country is operating in a surplus or deficit.

Care to guess how the US is operating?

No surprise, even after we net out services and income surpluses, we are running a deficit of $212B this past quarter.

OK, so now we know the US is operating in both a fiscal deficit and a current account deficit.

But what does this mean, and how is it both affected by and affecting the bond market?

🧐 Twin Deficit Hypothesis

Put simply, the Twin Deficit Hypothesis concludes that there is a connection between a nation's fiscal (budget) deficit and its current account (trade) deficit.

Let's walk through it.

As we noted above, when a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it runs a fiscaldeficit. To finance this deficit, it borrows money (issues bonds).

This increased borrowing can lead to higher interest rates as investors demand higher yield for the risk of persistent, long-term inflation (i.e., bond vigilantes have entered the chat).

Incidentally, if you have not read about the Bond Viglantes yet, I wrote all about them last week in The Informationist, and you can find that here:

Bond Vigilantes: They're Back

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week. 🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

Back to the Twin Deficits.

Higher interest rates will attract foreign investment, leading to an appreciation of the country's currency. This is called interest rate parity, where investors sell their own bonds and currency and buy foreign currency to then buy foreign bonds that have higher yields.

A stronger currency can make foreign goods cheaper, potentially increasing consumer spending on imports.

You see where this is all going, right?

Exactly.

Then as imports rise (and if exports stay the same or decrease), a trade deficit can occur, or in the case of the US, it simply widens

In this way, the two deficits remain tethered.

fiscal deficits → leads to more debt → leads to higher interest rates → leads to stronger currency → leads to more foreign investment, less foreign buying of domestic goods & more domestic buying of foreign goods → leads to higher current account deficits

So, in this way, the fiscal deficit (government spending) and the current account deficit (trade balance) move together, creating what is called Twin Deficits.

But wait. Here in the US, it gets even better.

😨 A Third Deficit?

Within these two deficits is embedded a third deficit, which just exacerbates the other two.

Some of you may have already guessed what it is.

And although the Fed calls it a 'deferred asset' on its books, in reality, it is a massive and growing liability.

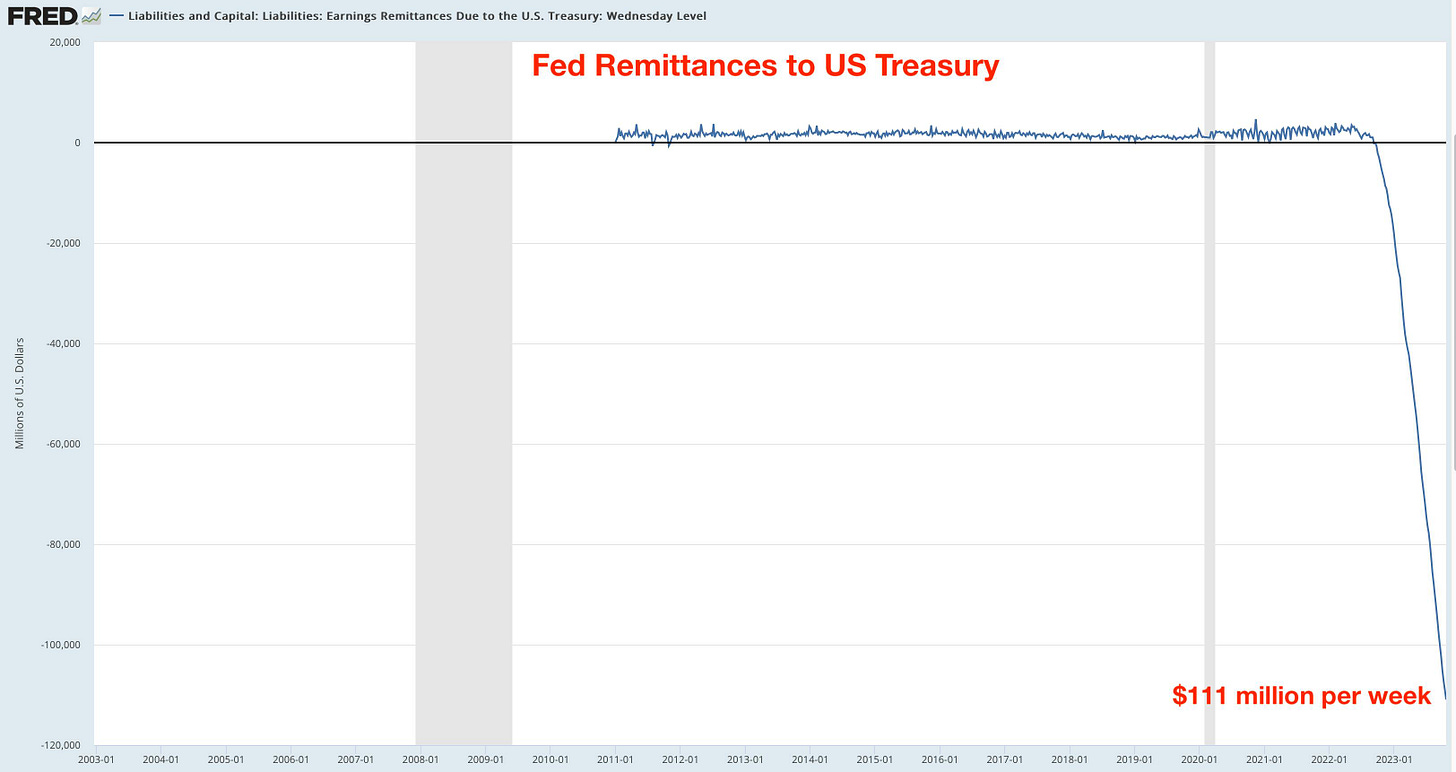

That's right. The Fed Remittences.

See, the Fed is supposed to be remitting its profits back up to the Treasury. This helps to lower the fiscal deficits and lessen the burden of debt.

But the Fed is in the Red.

Because, due to the effects of QE 2020, the Fed has been running massive deficits itself.

How?

The Fed printed money and essentially handed it to large banks, buying low interest USTs from them and putting them on their own balance sheet. The banks then took all this excess cash and now has it parked at the Fed in the Reverse Repo Facility as well as higher yielding short-term rates on Reserves. So the net/net effect is the Fed is paying a whole lot more interest on those reserves and that facility than it is making on the bonds it holds on its own balance sheet.

So they are running a loss.

How big of a loss?

Would you believe $111 million per week?

And the losses are piling up so fast, they are expected to add up to total over $134 billionby the end of 2023.

When you then consider that Fed Remittances were running at about a positive $110 billion in 2021, that is a difference of nearly a quarter trillion dollars.

And can you guess where that difference will be made up?

Bingo.

Just add it to the United States Treasury Mastercard account.

Pile on that debt, baby. And don't worry, we're good for it.

No, really.😬

🤑 What's Ahead

Well, seeing how rapidly we are piling on debt, having borrowed another $2.1 trillion in the last three months, there is little question the borrowing is not slowing down anytime soon.

Add to the fact that investors have woken up to this reality, (Bond Vigilantes are back) their demand for higher yield is only adding to the deficit, due to higher interest costs.

Fiscal Deficit grows.

Higher interest rates are also leading to a stronger US dollar.

Current Account Deficit grows.

Higher interest rates means Fed Remittances are in further deficit.

Fiscal Deficit grows.

And this is all before we even enter a recession.

When that happens, tax revenues shrink, unemployment and other entitlements rise, and—you guessed it—the fiscal deficit widens even more.

The Triple Deficit.

I do believe that when the pain gets big enough, the deficits grow large enough, the Treasury and Fed will have little choice but to activate their Twin Superpowers and press that magic money printer button again.

Then they will buy UST debt to keep interest rates from spinning up and out of control—and hence, the debt spiral 🌀— saving the bond market. At least on its face.

But, in reality, crushing the real rates with massive, unprecedented inflation to come.

So be wary, very wary, in your own portfolios and exposures.

Many of you already know that I am.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about the Twin Deficit Hypothesis and are ready to start incorporating some of this knowledge in your own investment process.

If you enjoyed this newsletter and found it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️