💡 The Truth About Tulip Mania and Bitcoin

Issue 195

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

The Great Tulip Myth

A Parade of Fads

The Anatomy of a Real Bubble

Why Bitcoin Refuses to Die

Inspirational Tweet:

It seems there is not a day that goes by without a news pundit, investment expert, or even PhD economist sounding the alarm, calling Bitcoin nothing more than a tulip.

They are referring, of course, to the famous rise and fall of tulips back in 17th century Amsterdam. The famous and spectacular speculative bubble that burst to the detriment of many investors and, well, speculators.

So let’s talk about tulips.

Not the oversimplified version you learned in economics class. Not the cautionary morality tale about Dutch greed. Let’s talk about what actually happened all those years ago.

And once you understand what tulipmania really was, you’ll understand why comparing Bitcoin to tulips may not actually make much sense at all.

Or does it?

Well, we are going to answer that and a while lot more, nice and easy as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a big cup of coffee, and settle into your favorite seat for a short but powerful history lesson about bubbles with this Sunday’s Informationist.

Partner spot

Bitcoin in 2025: A Year in Review—A shifting landscape in law, liquidity, and legacy

Was 2025 just underwhelming, or did bitcoin quietly lay the groundwork for an extended bull run?

On December 17 at 1 PM CST, Conner Brown, James Lavish, and Preston Pysh join Unchained for a high-signal breakdown of the forces that defined bitcoin this year.

They’ll cover:

How 2025’s macro and liquidity shifts reshaped bitcoin’s market footing

The policy developments in Washington that carried the most weight

What this year’s inflection points reveal about bitcoin’s long-term direction

If you want clarity on what 2025 really meant for bitcoin—and how to think about the road ahead—this is the event.

Wednesday, Dec 17 at 1 PM CST — online, free to attend.

🌷 The Great Tulip Myth

Tulipmania.

It’s hard to be an investor these days without hearing some sort of reference to this extraordinary event.

Thing is, it’s been embellished and twisted a bit to make the story seem nothing short of fantastical. Legendary, in fact. But it’s not exactly true.

Let me show you what I mean.

Here’s the story you’ve probably heard: In the 1630s, the Dutch went absolutely insane for tulip bulbs. Prices skyrocketed. A single bulb could buy a house. Peasants mortgaged their homes. And then one day in February 1637, the market crashed, destroying the Dutch economy and leaving thousands bankrupt.

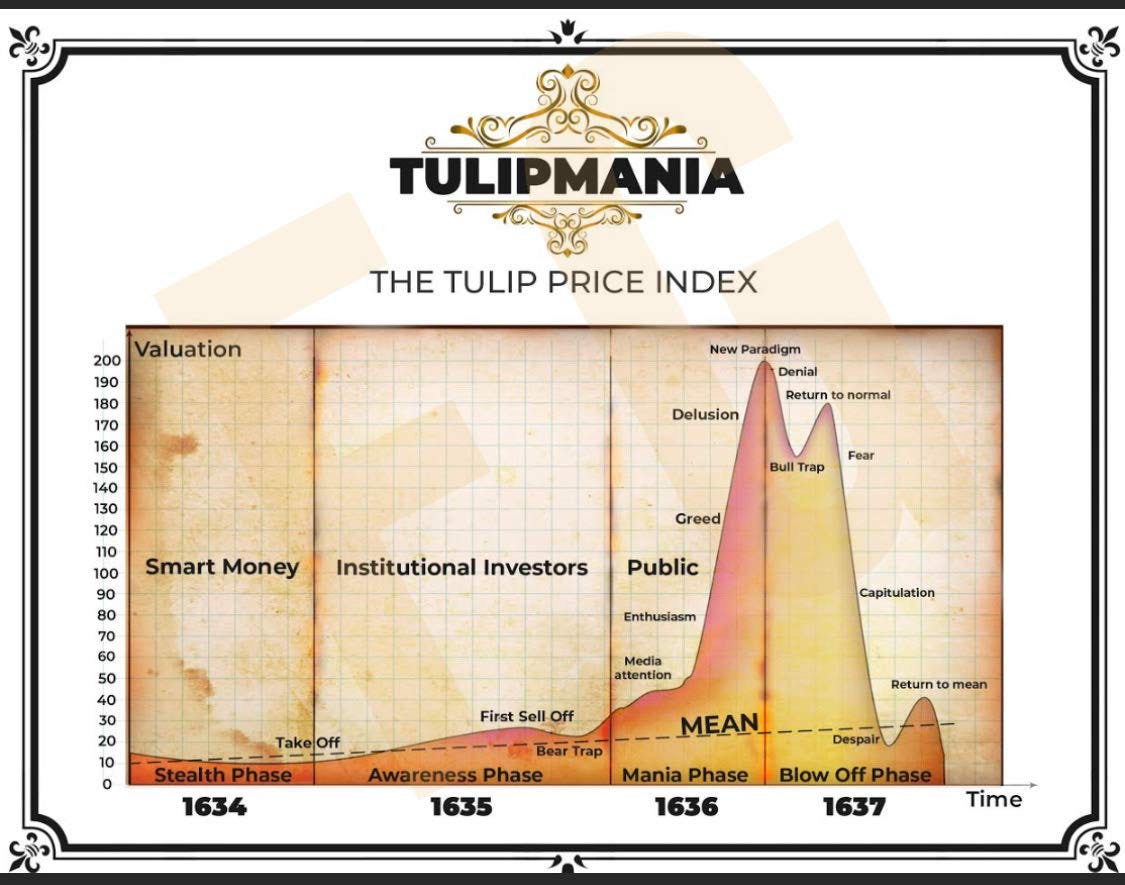

A chart like this may accompany the story:

This shows a stylized version of a price index reconstructed by the late Earl Thompson, a UCLA economist who studied the tulipmania extensively.

Mapped onto the classic bubble template, complete with “Smart Money,” “Institutional Investors,” and the “Public” piling in at the top, the price spike from late 1636 into early 1637 looks absolutely parabolic.

According to Thompson’s data, tulip contracts rose by roughly 20-fold between early November 1636 and February 3, 1637, then collapsed back to about their November level by May

A drawdown of roughly 95% from the peak.

For one coveted variety, the Switsers bulb, prices jumped on the order of twelve-fold between late December 1636 and early February 1637. Yes, just 5 weeks.

On February 3, 1637, prices collapsed. And by May, they were back near where they had started.

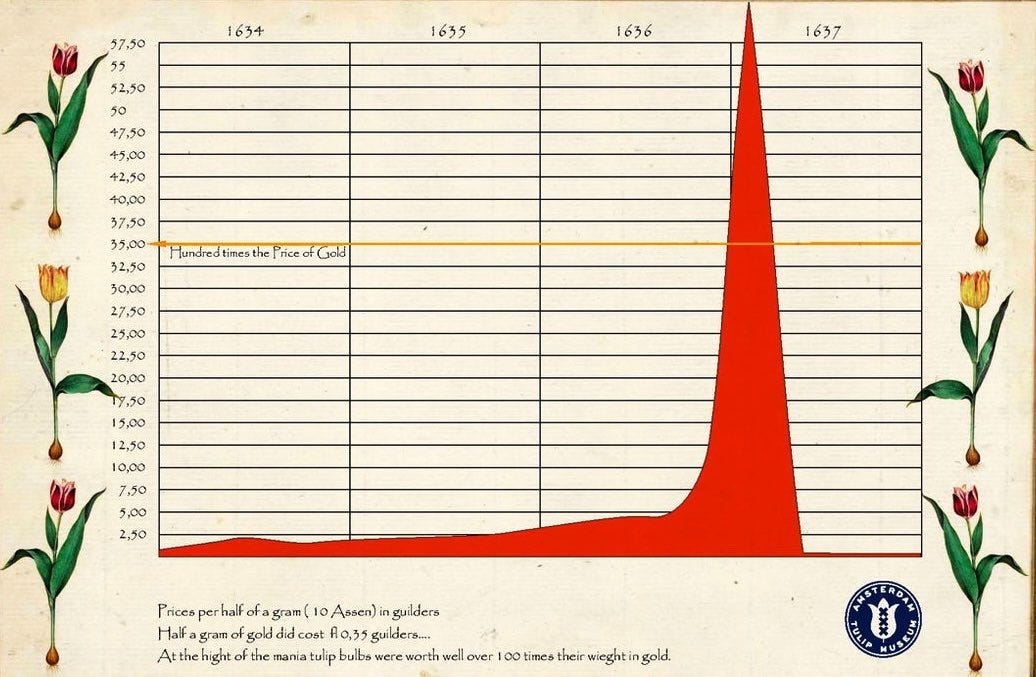

Here’s another visualization from the Amsterdam Tulip Museum that puts the mania in even starker terms:

This chart shows tulip prices in guilders per half-gram of bulb weight.

See that orange line? The one that is labeled “hundred times the price of gold”?

Right. Using the numbers from the chart, we can calculate that at the peak, tulips reached roughly 160× their weight in gold.

So yes, the price spike was real. The mania was real. For a brief moment, some tulip bulbs really did trade for more than their weight in gold.

But then look at what happens next.

In the data, prices shoot up once, crash, and then sit back near their pre-mania levels. They never come close to the 1637 spike again. That’s the visual signature of a classic bubble:

One dramatic spike, one catastrophic crash, and then… nothing.

Burn that image into your memory, because we’re going to come back to it.

But here’s the thing about tulipmania: while the price chart is broadly accurate, almost everything else you’ve heard about it is wrong.

The economic devastation? The mass bankruptcies? The destroyed fortunes?

Well. It turns out that none of that actually happened.

The Truth

The tulipmania narrative we know today comes primarily from a book written over 200 years after the fact, Charles Mackay’s 1841 Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Mackay was a Scottish journalist with a gift for colorful storytelling and a moral axe to grind about the dangers of speculation.

Surprise, surprise, Mackay wasn’t a historian.

No, for his research, he leaned heavily on satirical pamphlets written by Dutch moralists who wanted to mock speculators, not document accurate prices. Turns out, those pamphlets spun wild tales of chimney sweeps and servants gambling away their life savings and claimed the crash ruined the Dutch economy. For the next 180 years, economists and pundits repeated his stories without ever checking the primary sources.

It seems ironic that one of the key mantras of Bitcoiners is, Don’t Trust, Verify.

In any case, in 2007, a historian named Anne Goldgar did something radical: she went to the Dutch archives and looked at the original records.

I know. Groundbreaking journalism. The likes we don’t ever see in modern mainstream media.

And what she found was remarkable.

First, let’s talk about who was actually trading tulips.

According to Mackay, everyone from nobles to chimney sweeps was swept up in the mania.

Goldgar found something very different.

In years of digging through notarial records, court cases, wills and account books, she identified only about 350 people involved in tulip trading in the 1630s, and they were overwhelmingly wealthy merchants and skilled artisans, exactly the sort of people you’d expect to speculate in luxury goods. No evidence of peasants or chimney sweeps risking their livelihoods.

And those legendary prices?

Goldgar found only 37 individuals who paid more than 300 guilders for a tulip bulb, roughly a year’s wages for a skilled craftsman. The most expensive tulip receipt she found was for 5,000 guilders, about what a nice Amsterdam house would have cost at the time.

Yes, 5,000 guilders was an absurd price. But it was paid for the rarest bulbs, and it was a major outlier.

Economist Peter Garber, who compiled data on 161 bulb sales across 39 varieties, shows that his highest price observations largely come from a single charity auction in Alkmaar on February 5, 1637, held to benefit the children of a deceased tulip dealer, what both he and the Amsterdam Tulip Museum point to being the peak of the mania.

And Garber makes another useful comparison: in the 1980s, a prototype lily bulb reportedly sold for the equivalent of about $480,000 at contemporary exchange rates. Collectors have always been willing to pay crazy money for rare botanical specimens.

That doesn’t mean there was a “lily bubble.”

The “Crash” That Wasn’t

Here’s where the story takes an interesting turn.

The popular narrative says the crash in early February 1637 bankrupted thousands and wrecked the Dutch economy.

Goldgar’s archival research tells a different story.

In the thousands of pages she combed through, she found fewer than six people who appear to have run into serious financial trouble during those years, and it’s not clear tulips were the main cause. “I found not a single bankrupt” whose ruin could be pinned on tulipmania, she writes and has repeated in interviews.

So how can prices crash 90–95% without a wave of bankruptcies?

Well, one crucial detail that the popular story leaves out: most of the peak-season trading wasn’t for actual bulbs. It was for contracts.

A Key Detail

During the winter of 1636–37, the tulip trade largely took place in taverns on the basis of contracts for future delivery. Bulbs were in the ground; if you dug them up in mid-winter, you killed the plant. So traders did what traders always do when they want to speculate on something they can’t move around easily: they wrote contracts.

These were effectively futures (and, as some economists point out, often functioned like options): promises to buy or sell bulbs at a specified price when the bulbs could be lifted from the soil in the summer.

When prices collapsed in early February, buyers suddenly had no incentive to honor those contracts at the old, sky-high prices. Courts were reluctant to enforce them. After a period of wrangling, local authorities adopted a compromise: in Haarlem and other cities, buyers could cancel their tulip contracts by paying a fixed fee, ultimately about 3.5% of the original price.

In other words, a speculator who had agreed to buy a 1,000-guilder bulb could walk away for 35 guilders.

Because most of the late-stage mania was in these forward-style contracts, and many of those were defaulted or settled for a tiny fraction of their notional value, relatively little of the face-melting price action ever turned into realized cash losses.

Sellers were left holding bulbs worth far less than they’d hoped to receive, but they hadn’t actually banked the giant profits in the first place, they had mostly lost out on hypothetical gains.

A Speculative Episode, Not an Economic Crisis

So where does that leave us? Was tulipmania a speculative bubble?

By reasonable definitions, yes: prices in certain contracts rose far above any plausible fundamental value and then crashed.

But it was a tightly contained bubble:

It involved a few hundred wealthy traders, not “the population, even to its lowest dregs.”

It lasted only a few months at peak intensity (roughly December 1636–February 1637).

The Dutch Republic’s broader economy, then the richest in Europe, showed no sign of a crisis tied to tulips. The Dutch continued to enjoy the world’s highest per-capita incomes and remained a leading commercial and financial power for decades afterward.

Tulipmania was a vivid and somewhat embarrassing episode that became a moral fable. And that fable has been weaponized ever since by people who want to dismiss any asset they simply don’t understand.

Including Bitcoin.

🧸 A Parade of Fads

Before we get to Bitcoin, let’s be clear about something: real speculative manias do happen. Assets with no intrinsic value do get bid up to absurd prices. And when those bubbles pop, they stay popped.

Let’s look at a few examples from history:

The Mississippi Bubble (1719-1720). John Law was a Scottish gambler who convinced the French government to let him run their entire financial system. His scheme was clever: consolidate France’s crushing war debts into shares of the Mississippi Company, which supposedly held monopoly rights to the riches of French Louisiana.

Law printed money. He propped up share prices with buybacks. He promised dividends from gold mines that didn’t exist. The stock rose 20x in a single year. French nobles sold their estates to buy shares. When Law finally ran out of tricks in 1720, the bubble collapsed. The shares became worthless. The French economy was devastated for a generation. Law fled the country in disgrace.

The Mississippi Company never recovered. Not once. Not ever.

The South Sea Bubble (1720). Across the English Channel, the South Sea Company was running an eerily similar scheme—swapping government debt for company shares, bribing members of Parliament, and watching the stock price soar from £100 to over £1,000 in mere months.

The company’s actual business—trading slaves and goods with Spanish America—was a sideshow. The real product was financial engineering. Directors lent money to speculators so they could buy more shares. They closed the transfer books to prevent selling. They convinced Parliament to ban competing joint-stock companies.

When it collapsed in the fall of 1720, it took down half the British aristocracy. But the company itself limped on as a boring debt-holding vehicle until the 1850s. The stock? It crashed back to £100 and never recovered its highs. Not once. Not ever.

Cabbage Patch Kids (1983). These dolls triggered actual riots, including a store manager in Pennsylvania who used a baseball bat to defend himself from a mob., and a woman who broke her arm in a stampede. Dolls that retailed for $25 sold for $500 on the black market.