💡 The Fed's Favorite Lie: "This Isn't QE"

Issue 190

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

Why We’re Talking About This Again (And What Twitter Gets Wrong)

September 2019: What Broke and Why It Mattered

QE vs “Not QE”: Why the Semantic Debate Matters (But Also Doesn’t)

The Standing Repo Facility: A Ceiling, Not a Cure

Powell’s Warning & What’s Coming Next

Inspirational Tweet:

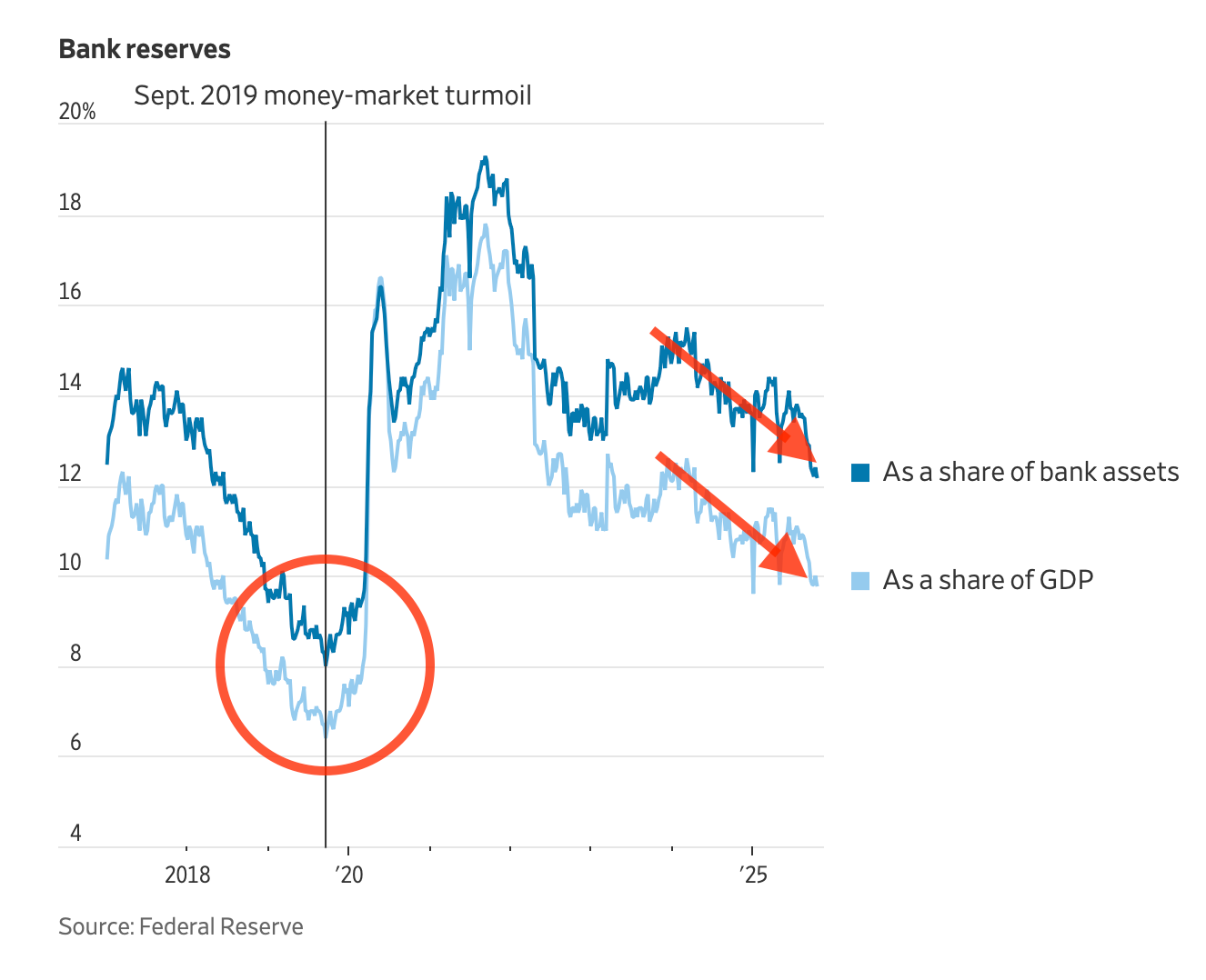

Two weeks ago, we talked about how quantitative tightening (QT) was ending and the Fed would have no choice but to expand the balance sheet again soon (QE).

Low and behold, this week, Powell confirmed it. QT ends December 1st.

But here’s the thing. My inbox and replies exploded with confusion, arguments, and frankly, a lot of misinformation about what this means.

“Powell would never do QE at these rate levels!”

“The SRF prevents another 2019!”

“You’re fear-mongering about something that won’t happen!”

So today, we’re going deeper. Not because I love talking about repo markets (who does, amiright?), but because understanding what happened in September 2019 is the key to understanding what’s about to happen in 2026.

We’re going to clear up the confusion between “QE, not QE,” open market operations, and bank reserve management. We’re going to look at exactly what broke in 2019 and why. And we’re going to unpack and decipher what Powell actually said this week, word for word, so you can see for yourself what’s coming.

But have no fear, because we are going to do it nice and easy, as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a big cup of coffee and settle into your favorite seat for a trip down Fed Memory Lane with this Sunday’s Informationist.

Partner spot

Is the fiat retirement system sinking? With markets uncertain, layoffs on the rise, and monetary policy shifting, it might be time to rethink how you protect your long-term savings.

In this special session, Mark Moss and Unchained’s Jeff Vandrew cover:

Why the “illusion of wealth” hides the true weakness of fiat-based retirement accounts

Why bitcoin’s scarcity and growth curve make it the cheat code for retirement planning

How rolling an old 401(k) into a bitcoin IRA could offer tax advantages and help build generational wealth

Learn how bitcoin can protect your purchasing power, strengthen your retirement plan, and offer a level of sovereignty no other retirement asset can.

Online and free to join!

🔥 September 2019: What Broke and Why It Mattered

Let’s start by setting the all-too-important scene of September 2019.

Donald Trump is president. Brexit is dominating headlines. And absolutely nobody has heard the word “coronavirus” unless they’re a virologist.

The economy? Buzzing along. Unemployment below 4%. Stock market near all-time highs. The Fed had been gradually raising rates and shrinking its balance sheet through Quantitative Tightening (QT) since 2017.

Everything was downright peachy.

Until Monday, September 17, 2019, that is…

The Day the Plumbing Broke

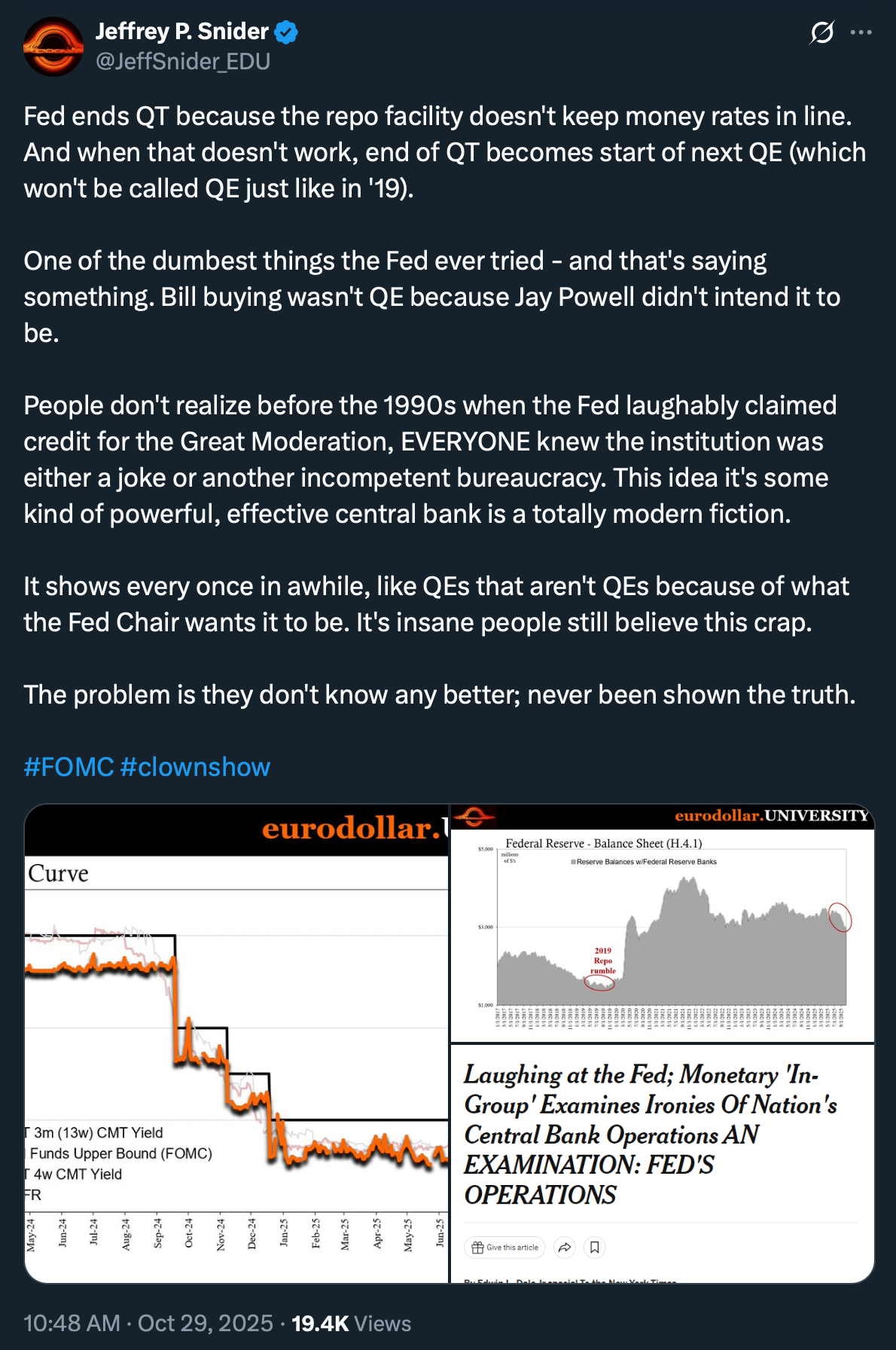

That morning, something broke in the obscure world of overnight lending markets. A super important interest rate called SOFR (the Secured Overnight Financing Rate) suddenly spiked higher.

This is the rate that banks and financial firms charge each other to borrow money. See, one bank sends US Treasuries to another bank, and that bank sends cash to the first one in return. The rate charged for that ‘secured loan’ is the SOFR.

Think of it like this.

You need some cash, say $100, to pay a medical bill. You have a Visa gift card with $100 on it (solid collateral). You ask your friend for a loan of $100 in exchange for the Visa card. Then once you get your next paycheck, you send the friend $100 you owe them plus a small tip for the gesture (this is the equivalent of the SOFR rate), and he gives you back your collateral (the Visa gift card).

Pretty simple, and usually a straightforward and easy (read: cheap) transaction among financial firms.

Not that day, though.

See that spike there? Some reports said that the rates went even higher intraday, like up to 9% or 10%.

For context, this would be like your variable mortgage rate suddenly tripling overnight.

Furthermore, the Effective Federal Funds Rate (the Fed’s own target rate) breached the top of its target range for the first time in over a decade.

The overnight lending market, the plumbing that keeps the entire financial system liquid and functioning, simply seized up.

Banks were desperate for cash.

By 9:30 AM on September 17th, the New York Fed announced emergency repo operations, offering to lend up to $75 billion overnight to calm the panic. Within weeks, the Fed announced they would start buying Treasury bills again.

Not to stimulate the economy. Not to fight a recession. But because they’d drained too much liquidity from the system and the financial plumbing had broken.

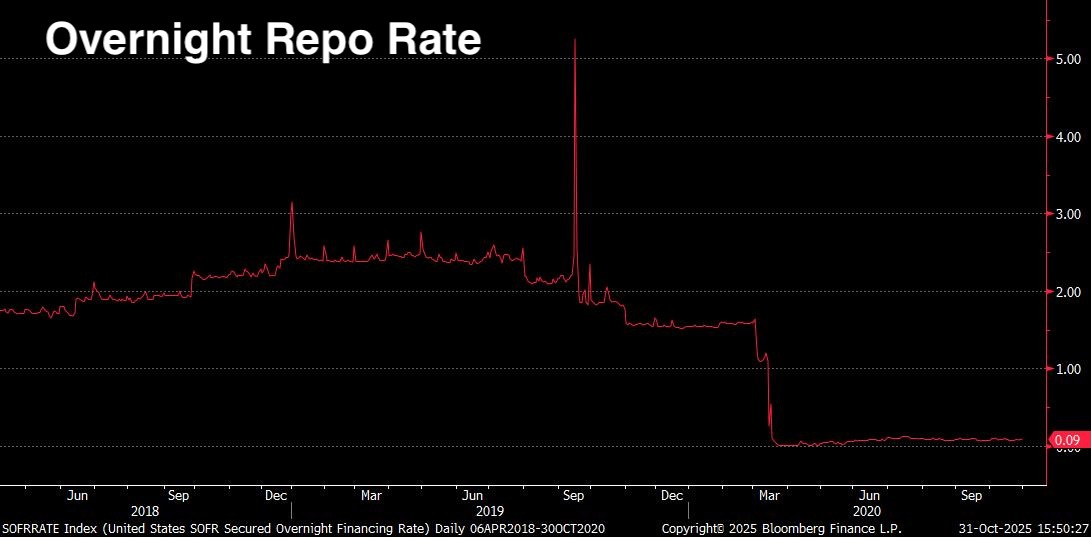

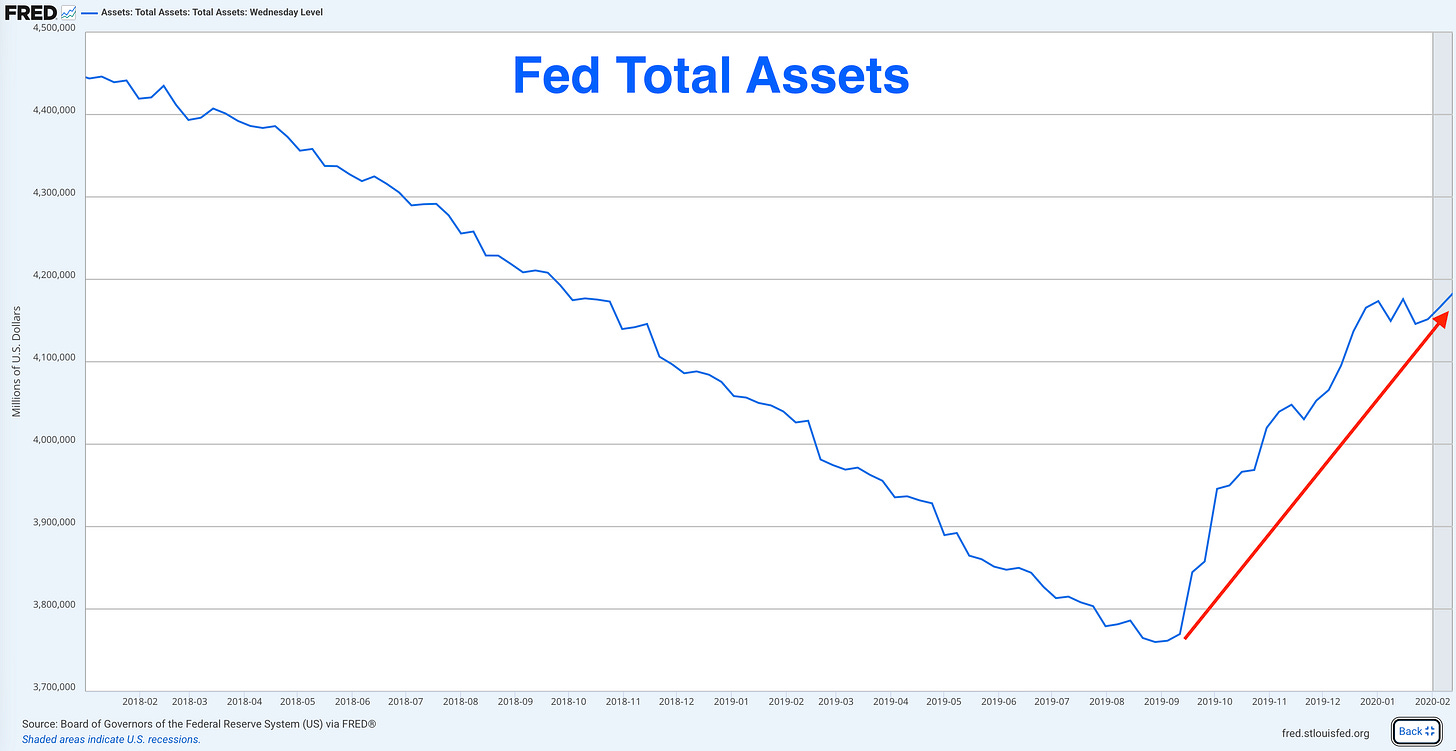

And you can see the Fed Balance Sheet started expanding again.

Two weeks ago, I warned you this was coming. We looked at the charts. We walked through the math. And I told you the Fed would have no choice but to stop QT and soon restart balance sheet expansion.

This week, Powell confirmed exactly that.

But to understand why this matters and what’s about to happen, we need to understand what actually went wrong in September 2019, and how it applies to today.

The Anatomy of a Liquidity Crisis

September 2019 wasn’t a random accident. It was the inevitable result of the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening experiment hitting that stealth brick wall called reality.

See, after the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned from under $1 trillion to over $4.5 trillion through multiple rounds of Quantitative Easing (The Fed buying US Treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities (aka MBS) in the open market).

By 2017, they decided it was time to shrink it back down through QT.

And so, each month, the Fed would let a certain amount of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities simply “roll off” its balance sheet. When securities matured, the Fed wouldn’t buy new ones to replace them.

This gradually drained reserves from the banking system.

By early September 2019, the Fed’s balance sheet had fallen from $4.5 trillion to about $3.7 trillion. Bank reserves (the cash that banks hold in their accounts at the Fed) had dropped to approximately $1.4 trillion.

Here’s the critical question the Fed was trying to answer: How low can reserves go before bad things happen?

And boy did they find out.

Simultaneous and Unfortunate Events

On September 16, 2019, two events collided:

1. Corporate Tax Payments

As many of you know, mid-September is a major corporate tax deadline. Companies withdraw reserves from the banking system to pay good ol’ Uncle Sam, temporarily draining enormous amounts of liquidity. An estimated $120+ billion was pulled from the system in the week leading up to September 17th.

2. Treasury Settlement

A large Treasury auction had just settled, requiring dealers to come up with approximately $54 billion to pay for the bonds they’d purchased.

On a normal day, this wouldn’t have been a problem. Banks would lend to each other in the overnight repo market, moving reserves around to wherever they were needed most.

But these weren’t normal conditions. Because of years of QT, the total pool of reserves had shrunk dramatically. And here’s the critical insight: reserves weren’t just too low in aggregate. They were unevenly distributed.

Some banks were sitting on plenty of reserves. Others desperately needed more. But the system had become segmented.

Some of you may be asking, if the banks had US Treasuries as collateral, why wouldn’t other banks lend to them?

Why Banks Wouldn’t Lend

This is where post-2008 regulations created an unexpected problem.

After the financial crisis, regulators implemented strict requirements like the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) and Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). Basically, these rules made it expensive for banks to lend out reserves, even when other banks were willing to pay high rates to borrow them.

A bank with excess reserves could have lent them out at 9% overnight. An amazing return! But doing so would have increased their balance sheet size, requiring them to hold more capital under the SLR. Many banks decided it wasn’t worth the hassle for a one-day loan.

So even though some banks had plenty of reserves and others desperately needed them, the normal arbitrage mechanism that should have smoothed this out...didn’t work.

The result? A liquidity crisis in the most important short-term funding market in the world.

The Fed had been conducting QT at a pace of up to $50 billion per month, assuming the system could handle it. They were wrong.

The September 2019 crisis taught the Fed a critical lesson: there’s a floor to how low reserves can go before the financial system starts breaking.

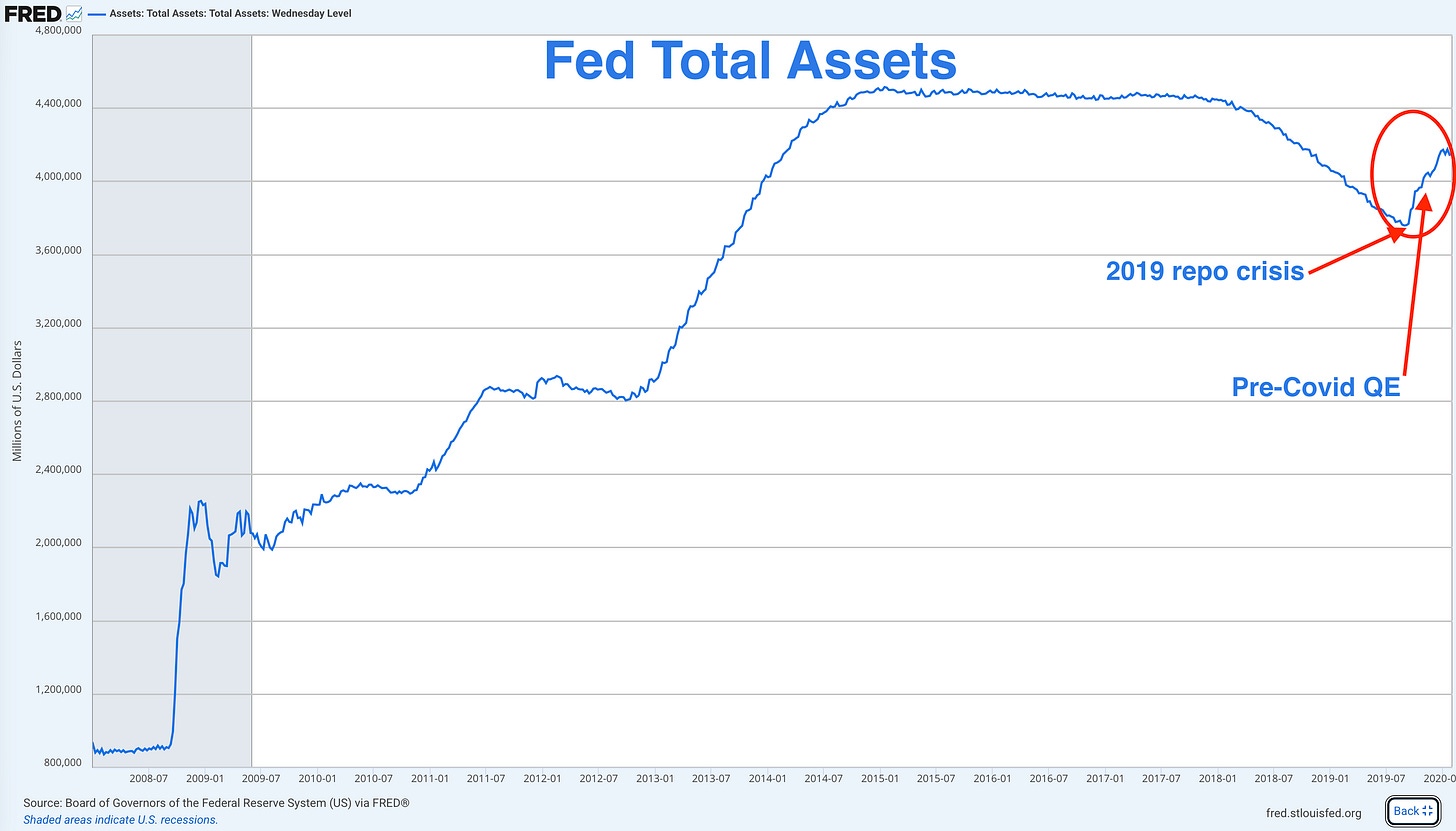

That floor is measured two ways:

Bank Reserves as a percentage of Total Bank Assets (dark blue line)

Bank Reserves as a percentage of US GDP (light blue line)

And as you can see in the chart above, we’re approaching the floor again.

🧐 QE vs “Not QE”: Why the Semantic Debate Matters (But Also Doesn’t)

Before we talk about what Powell said this week and what’s coming, we need to clear up some terminology. Because if you’re going to understand what the Fed is about to do, you need to understand the distinctions the Fed makes.

This is where a lot of the confusion comes from.

Open Market Operations (OMO)

These are temporary ‘repo’ operations where the Fed lends cash to banks overnight (or for a few weeks) against collateral. The banks have to pay it back. Think of it like the Fed writing a short-term loan.

In September 2019, the Fed conducted emergency OMOs:

Up to $75 billion overnight

14-day term repos for ~$30 billion

These operations roll off, they’re not permanent additions to reserves

OMOs don’t permanently expand the balance sheet. They’re liquidity management tools for temporary funding squeezes.

Standing Repo Facility (SRF)

This is essentially a permanent, pre-approved OMO that’s always available. Eligible institutions can tap it anytime at the posted rate (currently set at the top of the Fed’s target range).

The SRF was created in July 2021 specifically to prevent another September 2019 scenario. It’s a pressure relief valve.

But here’s the critical point: The SRF provides temporary funding that must be repaid daily. It technically does not add permanent reserves to the system.

If a bank borrows $1 billion from the SRF on Monday, they have to pay it back Tuesday morning. They can borrow again Tuesday, but it rolls off again Wednesday. This is fundamentally different from the Fed buying assets and permanently adding reserves.

Reserve Management / T-Bill Purchases

This is what the Fed did starting in October 2019. They bought short-term Treasury bills on the open market, paying for them by permanently crediting reserve accounts.

When the Fed buys a $1 billion T-bill:

They give the seller $1 billion in reserves (permanent)

The seller gives them the T-bill (which the Fed holds to maturity)

Those reserves stay in the system until the Fed actively removes them

This is balance sheet expansion. It does add permanent reserves. It does increase liquidity in the system.

From October 2019 through February 2020 (before Covid), the Fed’s balance sheet expanded by approximately $400 billion through T-bill purchases.

See?

Traditional Quantitative Easing (QE)

This is what most people think of as “QE.” The Fed buying long-duration Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to push down long-term interest rates and stimulate the economy.

Traditional QE:

Targets long-term rates (10-year, 30-year bonds)

Announced in conjunction with near-zero interest rates

Explicitly framed as “accommodation” or “stimulus”

What happened in 2008-2014 and again in 2020-2021

Why This Distinction Matters