💡The Fed's Cutting Rates, Why Are Mortgages Still Expensive?

Issue 196

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

The 10-Year Treasury Sets The Mark

Term Premium Awakens

The Treasury’s $10 Trillion Problem

Investment Implications (And What to Do About It)

Inspirational Tweet:

If you’ve been following the news lately, you’ve likely heard real estate brokers and some politicians proclaim, “If the Fed cuts rates, mortgages will get cheaper!”

Except the Fed did cut rates and mortgages are still expensive.

As are car loans and credit card rates.

So what gives?

See, there’s something the talking heads on TV don’t tell you. When the Federal Reserve cuts rates, they’re cutting the overnight rate—the rate banks charge each other for one-day loans.

Your mortgage? Your car loan? Your credit card?

Those may or may not respond to that overnight rate at all, as we are seeing now.

But why is this happening? What’s driving the disconnect? And what can you do about it?

All good questions, and ones we will answer—along with some others—nice and easy as always, here today.

So, pour yourself a big cup of coffee and settle into your favorite seat for a look into the great Fed rate-cut illusion with this Sunday’s Informationist.

Partner spot

Bitcoin in 2025: A Year in Review—A shifting landscape in law, liquidity, and legacy

Was 2025 just underwhelming, or did bitcoin quietly lay the groundwork for an extended bull run?

On December 17 at 1 PM CST, Conner Brown, James Lavish, and Preston Pysh join Unchained for a high-signal breakdown of the forces that defined bitcoin this year.

They’ll cover:

How 2025’s macro and liquidity shifts reshaped bitcoin’s market footing

The policy developments in Washington that carried the most weight

What this year’s inflection points reveal about bitcoin’s long-term direction

If you want clarity on what 2025 really meant for bitcoin—and how to think about the road ahead—this is the event.

Wednesday, Dec 17 at 1 PM CST — online, free to attend.

🤫 The 10-Year Treasury Sets The Mark

Let’s start with the basics, because understanding this is crucial to understanding why Powell’s rate cuts aren’t helping you at all.

The Federal Funds Rate is what the Fed directly controls. It’s the overnight rate, or the rate banks charge each other for very short-term loans, typically hours to days.

Great for bankers. Great for hedge funds doing overnight repo (borrowing dollars against their US Treasuries) trades.

Not so relevant for you.

Because when you borrow money for years or decades, like a mortgage or car loan, lenders need compensation for duration risk. I.e., the risk that inflation, fiscal chaos, or some other disaster eats into their returns over that longer period of time.

The 10-Year Treasury is where that risk gets priced.

And here’s the critical point that the TV talking heads forget to explain: the Fed does not control the long end of the yield curve through the Fed Funds Rate.

Bond investors do.

The Fed can set the overnight rate wherever it wants. But the 10-Year yield? That’s determined by millions of investors around the world making bets about inflation, government debt, and economic risk over the next decade.

And right now, those investors are demanding more compensation. Not less.

Take a look at this chart to see what I mean:

Starting in September 2024, the Fed began its rate-cutting cycle. You can see the blue stepped line clearly marching downward—50 basis points in September, 25 in November, 25 in December. The Fed has cut a full 100 basis points.

Now look at the white line. That’s the 10-Year yield.

It did the exact opposite.

When the Fed started cutting in September, the 10-Year was sitting around 3.6%. By January, it had climbed to nearly 4.8%.

The Fed cut 100 basis points. The 10-Year rose over 100 basis points.

That’s not supposed to happen. In a normal easing cycle, long-term rates fall along with short-term rates. That’s kind of the whole point of cutting rates, to ease financial conditions across the entire economy.

But we’re not in a normal easing cycle.

And what does this mean for you?

Take a look at this chart of the 30-Year Fixed Mortgage Rate this fall:

The Fed cut rates in September 2025. They cut again in November. And again in December.

And the 30-Year mortgage? It’s sitting at 6.31%. Barely moved. In fact, look at December—after the latest Fed cut, mortgage rates didn’t budge at all.

So much for relief.

The spread between the 10-Year and Fed Funds is now at its widest level since November 2022.

What does that mean

It means the bond market is sending a very clear message: We don’t believe you, Jay.

But why? Why are bond investors refusing to follow the Fed’s lead?

😤 Term Premium Awakens

The answer comes down to something called the term premium.

This is the extra yield investors require to lock up their money in long-term bonds instead of rolling over short-term bills (Translated: Short Term Bills mature quickly, often in days or weeks, and so an investor most keep buying them over and over to stay invested, aka rolling over).

And so, think of the extra yield required as a “risk fee” for duration (longer investment period).

Normally, if investors believe inflation will stay low and the government will manage its finances responsibly, they don’t need much extra compensation. Term premium stays low or even negative—meaning investors are actually paying for the privilege of locking in rates.

But make not mistake: that era is over.

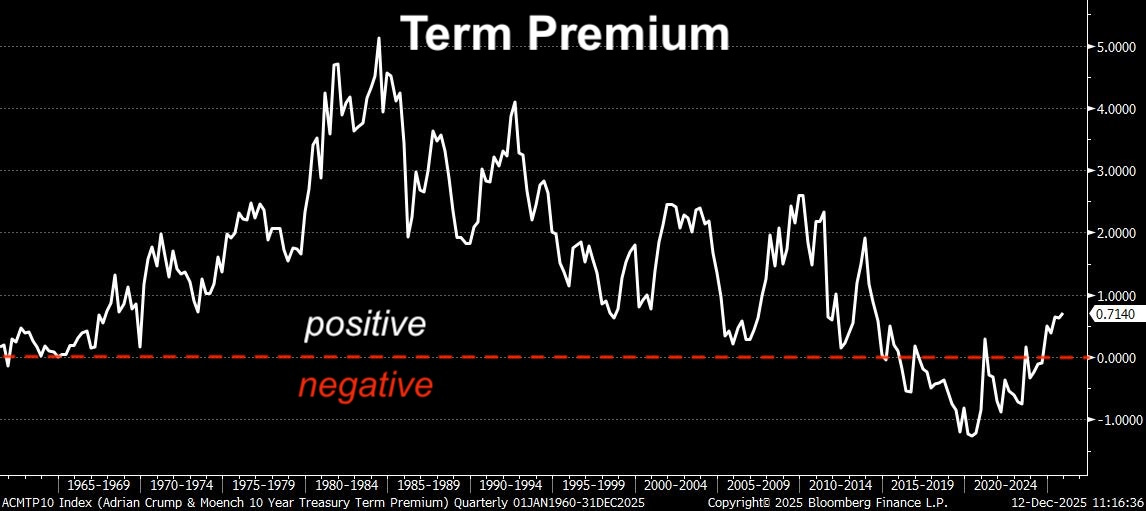

Take a look at this chart:

This is the Adrian, Crump, and Moench Term Premium model from the New York Fed. It’s the gold standard for measuring this.

You can see the term premium peaked at over 5% in the early 1980s—when inflation was raging and Volcker was jacking rates to the moon. Then it went on a 40-year slide, eventually going negative in the mid-2010s through 2020.

Wait, you may be asking, why did it go negative?

Good question, and the answer is: Quantitative Easing. The Fed was buying trillions in long-term bonds, artificially suppressing yields. Investors didn’t need extra compensation because the Fed was their backstop.

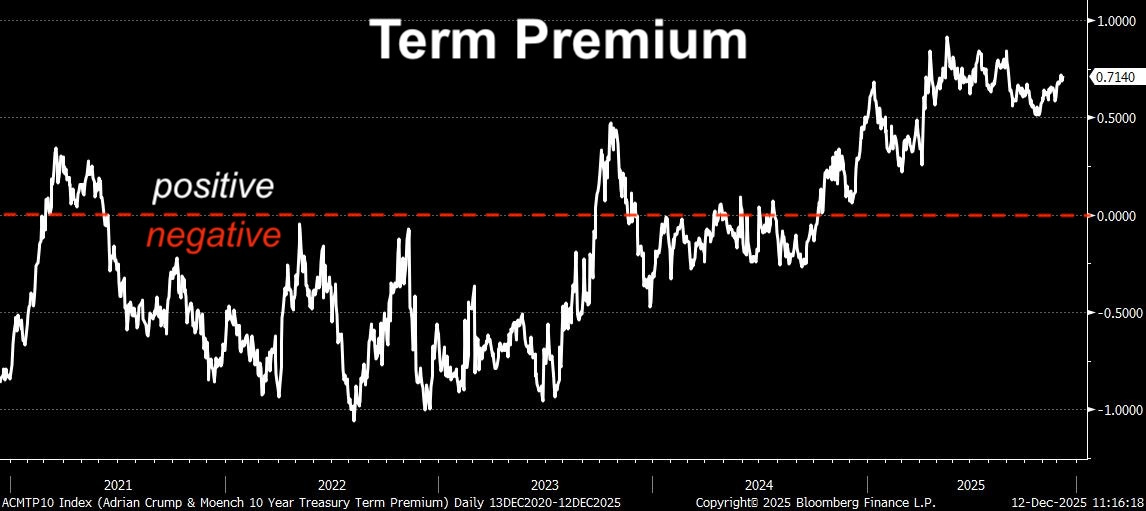

But look at what’s happened since 2020:

The term premium has gone from minus 1.2% in 2020 to plus 0.71% today.

That’s a 190 basis point swing.

This explains most of the “mystery” of why the 10-Year hasn’t followed the Fed down. Investors are demanding more compensation to hold long-term government debt. Not less.

But why are investors suddenly demanding more compensation?

Two main reasons: inflation expectations and fiscal dominance.

On Inflation

When the Fed cuts rates while inflation remains above target, bond investors get nervous. Lower rates typically stimulate the economy and can reignite inflationary pressures.

But it’s not just rate cuts that have investors concerned.

On December 1st, the Fed officially ended Quantitative Tightening. And just this month, they announced they’re resuming bond purchases, $40 billion in T-Bills to start, with an ongoing program of around $20 billion per month after that.

Now, you’ll hear plenty of debate on Twitter about whether this is “traditional QE” or “reserve management” or “Not-QE QE” or whatever term makes the Fed feel better about itself.

Let’s be honest here, shall we? Something the Fed seems to struggle with lately.

That fact is, the term they use is merely semantics. Or perhaps purposeful obfuscation is a better description.

Here’s what matters: The Fed is expanding the money supply. Period.

When the Fed buys bonds, they create new dollars out of thin air to do it. That’s literally how it works. Whether you call it QE or reserve management or “liquidity support” doesn’t change the mechanics. More dollars chasing the same goods and assets equals inflation.

Bond investors see this and realize: They’re cutting rates AND printing money? Inflation isn’t dead, they’re fueling it.

On Fiscal Dominance

This is quite honestly the bigger issue. Fiscal dominance occurs when government debt levels become so large that monetary policy becomes subordinate to fiscal policy. The Fed can no longer act independently because the government’s borrowing needs overwhelm everything else.

I know many have heard this from m before, but for those who are new around here or who haven’t heard me talk about the debt spiral, it’s simple:

The US now has $38.5 trillion in debt. Annual deficits are running $2 trillion. Interest payments alone are approaching $1 trillion per year. There’s no political will to cut spending, none. And the Treasury has to refinance roughly a third of that debt every single year.

And here’s the best part: Why do you think the Fed just announced they’re buying T-Bills again?

It’s not because the economy needs stimulus. It’s because the Treasury needs help.

The Fed has become the Treasury’s backstop. Its enabler. Its co-dependent partner in fiscal recklessness. This is fiscal dominance in action. The Fed subordinating its inflation mandate to the government’s borrowing needs.

And if we are pointing the finger here, it isn’t at the Treasury either, as they’re just charged with managing the government’s wildly out of control budget.

The true villain here is Congress, the body that spends all this money.

In any case, bond investors see this and think: The Fed isn’t independent anymore. They’re just printing money to help the government run deficits. And we’re going to demand higher yields to compensate for the inflation that’s coming.

The bond vigilantes, dormant for decades while the Fed ran QE and suppressed yields, are sleeping no more.

And it’s the Fed who has jarred them awake.

💣 The Treasury’s $10 Trillion Problem

OK, but why specifically does the Treasury need the Fed’s help?

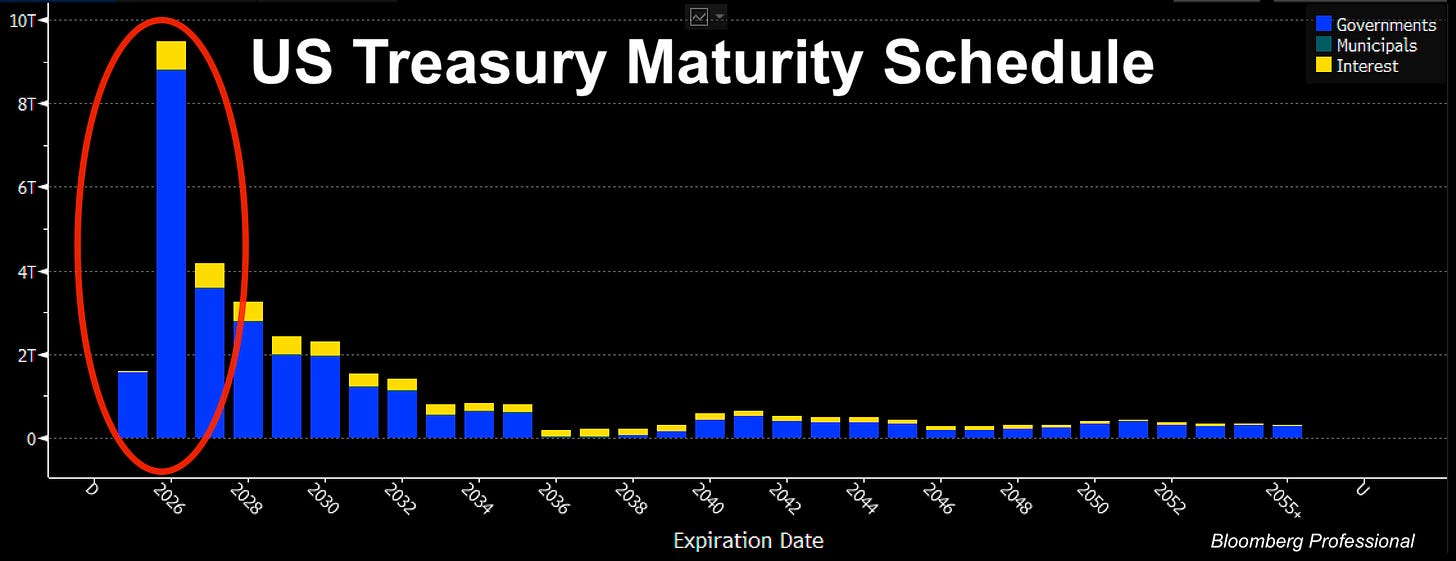

Take a look at this chart:

See that 2026 bar? With the 2025 debt maturing, the US Treasury will have over $10 trillion in debt maturing in 2026 alone. That’s about a third of all marketable Treasury debt.

In. One. Year.

Here’s the problem.

For years now, the Treasury has been playing a dangerous game. When rates were near zero during COVID, the smart move would have been to “term out” the debt, i.e., issue lots of long-term bonds and lock in low rates for decades.

Did Janet Yellen do that?

Nah. Instead, she leaned heavily on short-term T-Bills.

Why? Because T-Bills are easy to sell. Money market funds gobble them up. There’s always demand. And it made the interest expense look lower in the short term.

Brilliant financial engineering. World-class can kicking. Or…absolute idiocy. 🤡

Because T-Bills mature fast. Weeks to months. That means the Treasury has to constantly refinance. And when rates are higher (like now), that refinancing costs more.

It’s like having an adjustable-rate mortgage on $10 trillion. Fine when rates are low. Disastrous when they’re not.

The Treasury’s weighted average interest rate on debt has climbed from 2.3% five years ago to over 3.3% today. Net interest payments are now $1 trillion per year. More than we spend on defense.

And so, now the Treasury faces a choice.

Option 1: Keep rolling short-term debt and pray rates come down.

Option 2: Start issuing more long-term bonds to “term out” the debt and reduce rollover risk.

Here’s the catch with Option 2: If they issue more long-term bonds, they’re flooding the market with supply. But:

more supply at the same demand = lower prices = higher yields

They’re trapped.

Some of you may be asking: What if the Fed does Yield Curve Control, like Japan has done for so long? Can’t they just force long-term rates lower?

Good question.

And the answer is yes—technically, they can. Under Yield Curve Control (YCC), the Fed would commit to capping the 10-Year yield at some target level, say, 2%. Any time the yield rises above that target, the Fed steps in and buys bonds to push it back down.

But think about what’s actually happening here. The Fed becomes a bond trader themselves, actively manipulating the market and artificially suppressing rates.

And how do they buy all those bonds?

By printing even more money.

So yes, YCC can push long-term rates lower. But it does so by massively expanding the money supply. And what happens when you massively expand the money supply?

More inflation.

This is the trap. The Fed can either:

Let bond investors set rates (and watch yields rise), or

Suppress rates through YCC (and create even more inflation)

There’s no free lunch here. Either way, the purchasing power of your dollars gets eroded. In scenario one, you pay higher interest rates. In scenario two, you pay through the silent tax of inflation eating away at your savings.

Japan has been doing YCC for years, and what do they have to show for it? A currency that has lost over 50% of its value against the dollar since 2012. Last year, the yen hit 40-year lows.

YCC isn’t a solution. It’s just choosing which way you want to get squeezed.

The bond market sees all of this. The vigilantes understand the math. The Fed is trapped, the Treasury is trapped, and there’s no way out that doesn’t involve debasing the currency.

And that’s exactly why they’re demanding higher yields.

🏰 Investment Implications (And What to Do About It)

So what does all this mean for everyday Americans?

For borrowers: Rate relief isn’t coming yet. Even if the Fed cuts another 100 basis points, your mortgage rate, car loan rate, and credit card rate are tied to the 10-Year, not Fed Funds. And the 10-Year isn’t going down until the market believes inflation is truly dead and fiscal sanity has returned.

Neither seems likely. In fact, fiscal insanity seems to be accelerating.

That said, high inflation makes dollars cheaper when you are paying back those loans.

For savers: High rates on short-term instruments like money markets and T-Bills may persist even as the Fed cuts. Enjoy the yield while it lasts, but understand that inflation does eat away at your real returns.

For investors: This is where we can make up some ground, if done properly.

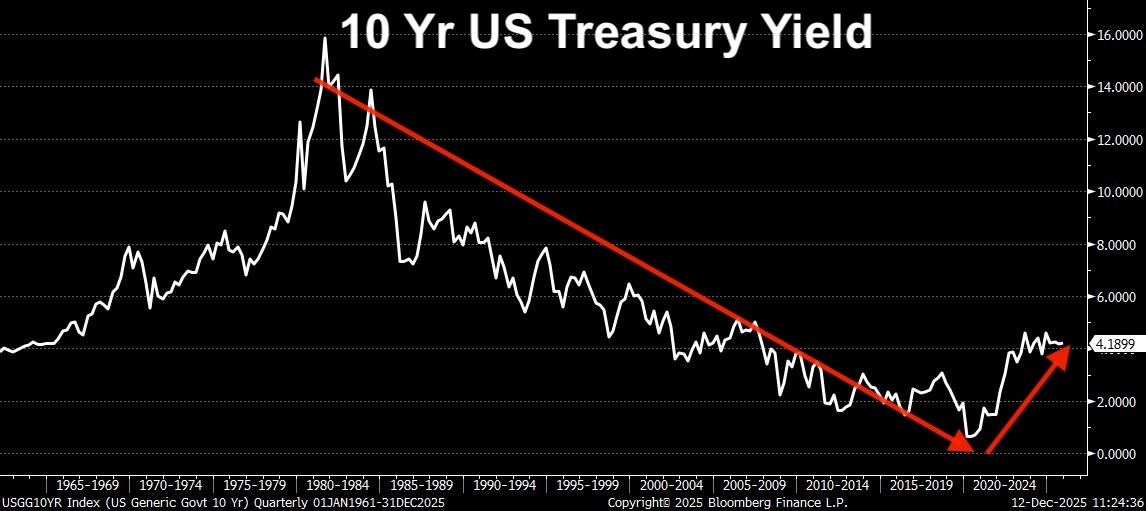

Take a look at this long-term chart of the 10-Year yield:

See those red arrows? For 40 years, from 1981 to 2020, the 10-Year yield was in a relentless downtrend. From over 15% at the peak of Volcker’s 1980s inflation fight, it fell and fell and fell, eventually bottoming below 1% during COVID.

Every time yields spiked, they made a lower high. Every time they fell, they made a lower low. It was the greatest bond bull market in history.

That trend has now broken.

Look at the right side of the chart. The 10-Year isn’t making lower highs anymore. It’s making higher highs. The 40-year downtrend line has been decisively cracked.

This isn’t a blip. This is a regime change.

We’ve gone from a world of structurally falling rates to a world of structurally rising rates. From a world where the Fed controlled the narrative to a world where bond investors are taking back control.

What works in a world of higher, stickier rates, persistent deficits, and a Fed that’s printing money to help the Treasury stay afloat?

Hard assets.

When governments run deficits they can’t afford and central banks print money to finance them, currencies get debased. It’s the only way out of the debt trap.

They won’t default. They’ll inflate.

The United States has three options:

Default (won’t happen)

Austerity (politically impossible)

Debasement (the only option)

They will choose door #3. They always do. In fact, with the Fed’s new T-Bill purchase program, they’re already choosing it.

Gold has protected wealth through every currency debasement in thousands of years of being a store of value. It doesn’t produce cash flows. It doesn’t have earnings. It just maintains purchasing power while fiat currencies march toward zero.

Bitcoin is this generation’s digital hard money, it’s more portable, more divisible, more verifiable, and absolutely scarce. Its monetary policy can’t be changed by any government, any central bank, any emergency. There will only ever be 21 million.

Though it is volatile as it is yet in its adoption phase, it is a long-term store of value.

Was about real estate? They’re not making more land, and desirable zip codes always find demand.

Bottom line: the 10-Year yield rising while the Fed cuts isn’t a bug. It’s a feature. The market is telling you that the future has more inflation, more debt, and more money printing than the Fed wants to admit.

So I personally own hard assets as a large percentage of my portfolio.

Gold and Bitcoin.

Mostly Bitcoin.

Because I personally don’t trust the Fed.

I don’t trust the Treasury.

And I don’t trust the incentive system we have in place for our so-called leaders.

I trust math. And I trust scarcity.

And you should too.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about the disconnect between Fed Funds and the 10-Year, why the term premium matters, why the Fed just started buying bonds again, and what it all means for you and your money.

If you enjoy The Informationist and find it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️

Investing in Gold should include the gold miners although I would stick with A1 jurisdictions (US, Canada and Australia). Yes there are mining risks but well managed miners provide a multiple to the price of gold.

James, totally onboard with your thesis seems almost bullet proof in the long run; however, I came across this video by Elon Musk (I know it's probably an AI simulation and not really Elon but the ideas are still valid IMO) I'd be interested in your thoughts, perhaps a good spring board for the next issue of the informationist. Here's the link: https://youtu.be/-I5sUnz1J7M?si=-UUZCEDCVioxIJx7 and here's another one that resonates with me as much as your work does: https://youtu.be/WVkWu2lg4Bw?si=JBR9IOdIZ_D55mSL Again, would be interested on your take. Thanks for preaching the sound money gospel, god knows we need it to reach as many people as possible.