The Economy Enters the D-Zone

Issue 73

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox:

Today’s Bullets:

Let’s define ‘default’

Tripping Covenants

Defaults lead to…?

Assume the position

Inspirational Tweet(s):

We’ve been hearing (and talking) about rising interest rates and the eventual onset of debt defaults, as a result. It appears the time is now upon us, and the outlook seems pretty ominous.

But just how bad is it, really, how much worse can (and will) it get, and what can we do about it as investors?

Super important questions at this point in the economic cycle, and ones we will tackle here today, nice and easy, as always.

So, grab your favorite mug of coffee and settle in for this Sunday’s Informationist.

Join the Informationist community to get access to subscriber-only posts and the full archive + ask questions and participate in the comments with other awesome 🧠 subscribers!

Partner spot

With an overwhelming stream of AI threads and newsletters, I’ve cut mine down to a few, and I personally like the clean and simple delivery of AI Tool Report.

You can check it out yourself for free, right here:

🤕 Let’s define ‘default’

First things first, let’s be sure we’re talking the same language and are all on the same page here. For the credit uninitiated, the terms can seem confusing when just tossed around by Wall Street nonchalantly.

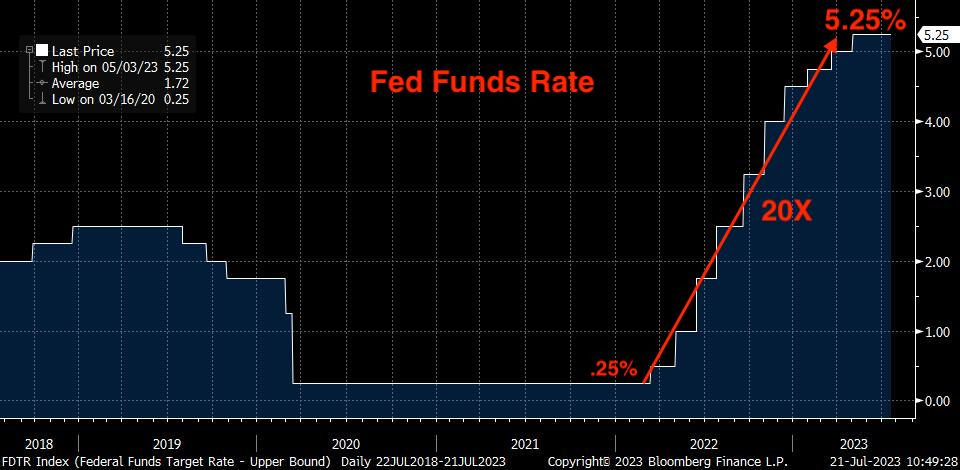

As we’ve been watching, the Fed has raised their target rate in a meteoric fashion, taking the overnight benchmark from 0.25% to 5.25% in a little over a year.

That’s not just a 5% rise in rates, that’s over 20X hike from the ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) level of 25bps.

Whoa.

Remember: The Fed sets the Fed Funds rate, this informs the overnight rate (annual rate at which banks lend to each other for short term borrowing), and this informs what rate banks are willing to lend to corporate or consumer borrowers.

Does this mean companies borrowing costs are now 21X higher than last year?

Not exactly.

We will keep it super simple here, but let’s walk through an example for illustration.

Let’s say a company has been borrowing money on a floating rate line of credit to leverage their business, allowing them to create more inventory and hence expand sales and faster, etc.

Say their earnings are $100,000.

Let’s then say that the rate the company was borrowing $1 million at last year was 6%, for an annual cost of $60,000.

Which means their earnings, net of interest, was $40,000.

But now, with the rise in Fed Funds, and hence the rise in bank lending rates, their new cost of capital may be closer to 12%, or $120,000. Especially because their debt coverage ratio (a company’s earnings divided by its interest costs) was so low.

Which makes their earnings?

Negative $20,000.

So, unless the company can find another place to borrow money or somehow sell more stuff faster or at a higher price, they have no choice but to fail to make payments on their debt. They just don’t have the money.

So they default on the debt. Simple as that.

But is it?

😬 Tripping Covenants

Also known as a technical default, when a company trips a covenant, it has violated a term or condition of the loan other than the payment obligation.

These covenants are put in place by lenders to signal potential liquidity or cash management problems at a company—to give the lenders a heads-up.

Covenants often have to do with a company's financial ratios, like its debt-to-equity or interest coverage, or maybe a clause that restricts the company from taking certain actions, such as acquiring new debt or selling key assets without the lender's approval or consent.

In a period of rising interest rates, covenants can become even more important, as higher interest rates might make it more challenging for a company to meet its financial targets, increasing the risk of tripping a covenant.

And when a company trips a covenant, it is in technical default on the obligation and the lender has the right to take action.

Actions can be things like demanding immediate full repayment of a loan or perhaps adjustment of the interest rate.

In reality, when a company trips a covenant, they typically ask the lender to waive or amend the terms of the breach, and if unsuccessful, they will then enter negotiations with the lender to find what is called a ‘cure’.

Cures can be raising capital, selling assets, reducing costs, or other actions to improve its financial ratios, or simply reversing any actions that violated the loan's terms. If the technical default is not resolved, it would likely lead to a payment default.

This, of course, often leads straight to bankruptcy.

But before digging into that, let’s take the market’s default temperature.

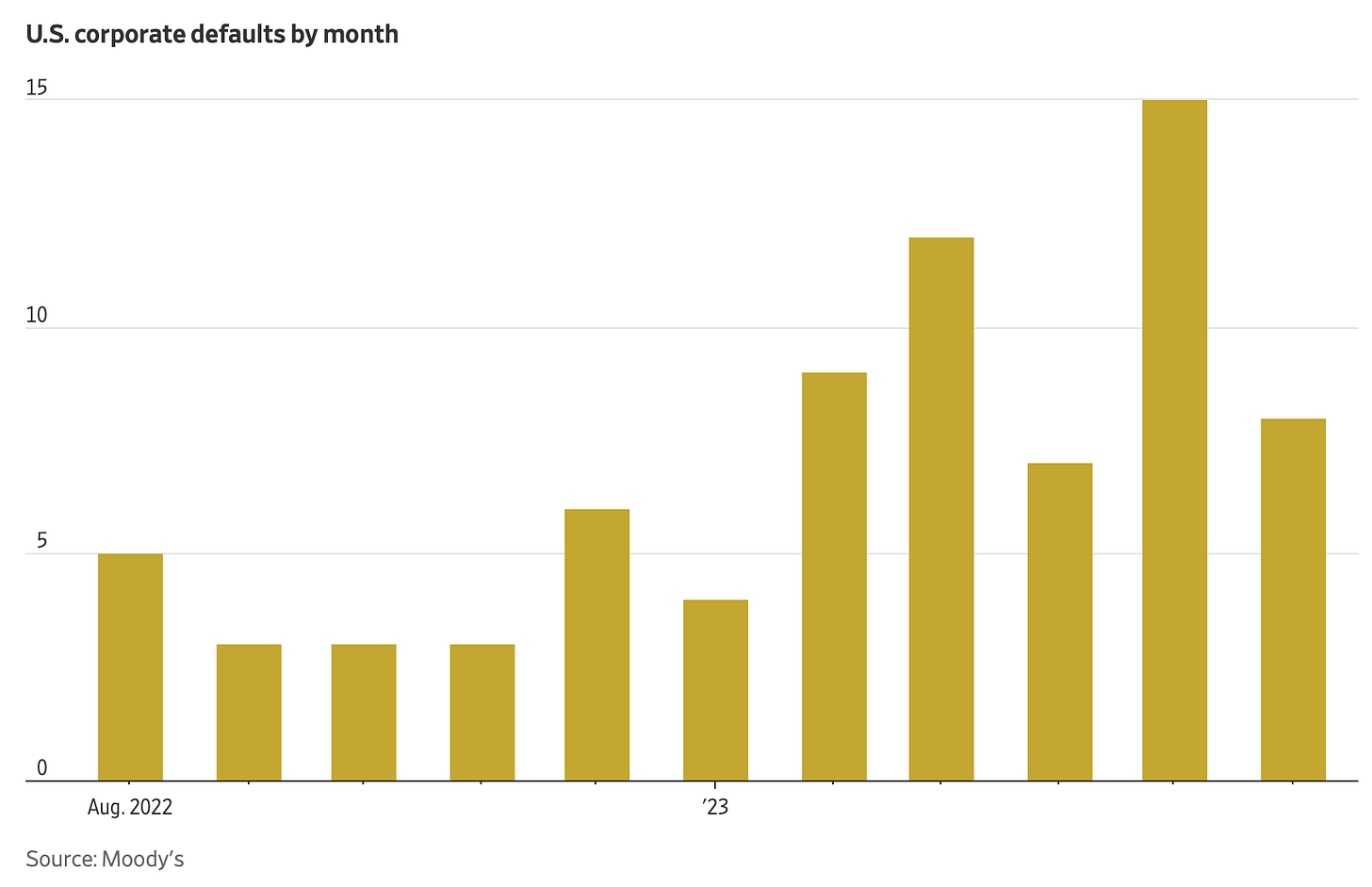

Well, through June, the US has seen fifty-five defaults. That’s about 50% more defaults thus far this year versus a total of thirty-six defaults in all of 2022.

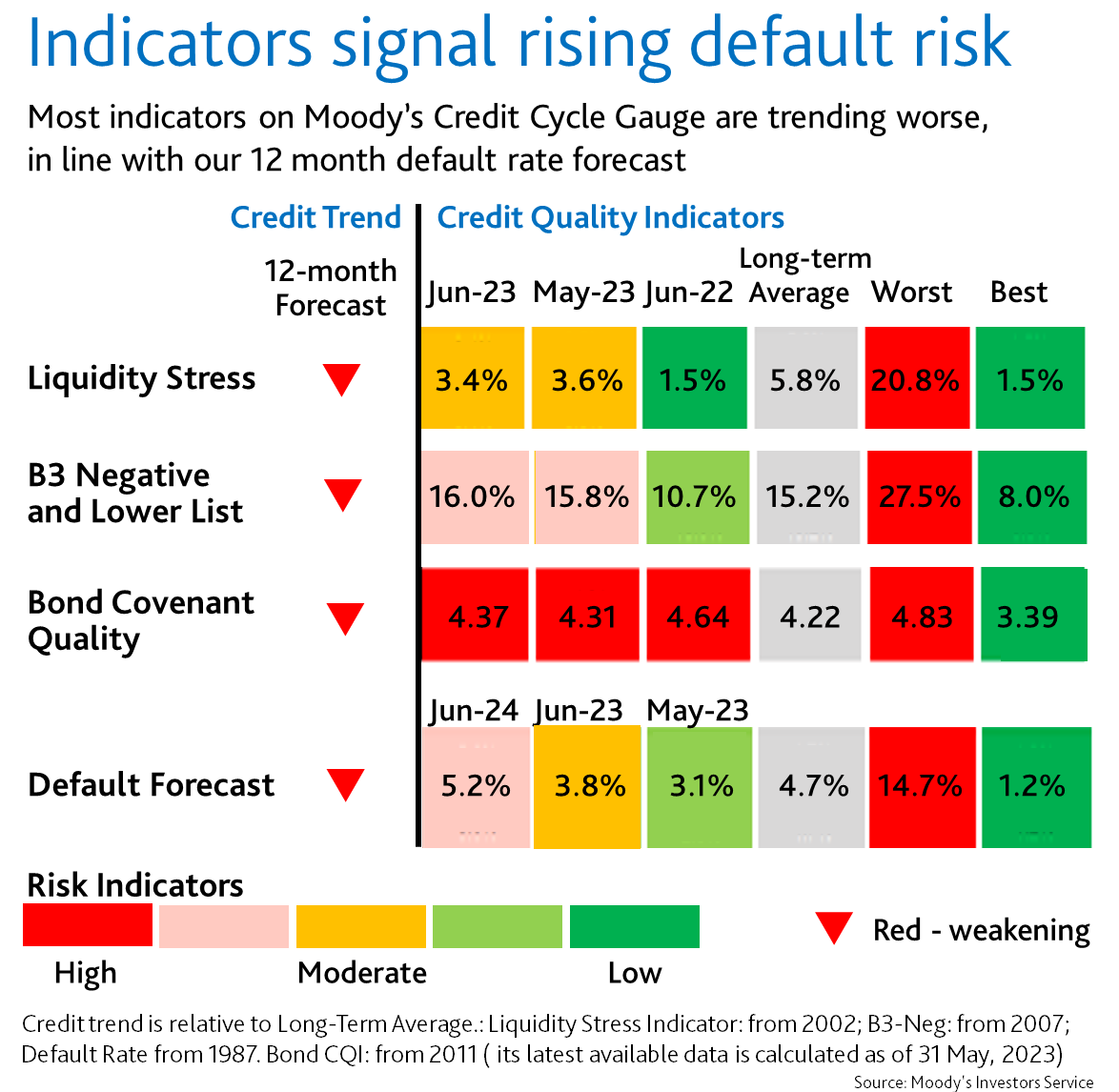

As of now, Moody’s is forecasting the default rate for 2023 to reach 4.7%.

That’s the base case.

But…Moody's "severely pessimistic” scenario has the global default rate reaching 14.7%, which is higher than the peak in the 2008 financial crisis.

An unlikely scenario that would mean an unemployment rate of 8% and significant economic downturn.

Bottom line: We are officially entering the default period, or what I like to call the D-Zone of the economy.

Let’s dig further.

One of the leading indicators of potential defaults is the SOFR-OIS spread.

Say what?

Let’s break this apart. SOFR stands for Secured Overnight Funding Rate, and this is simply the average rate that banks charge each other to borrow overnight (or a few days). And OIS is the Overnight Index Swap rate, which is a fixed rate that the banks can charge each other, using derivatives.

So, SOFR is floating (or variable), and OIS is fixed.

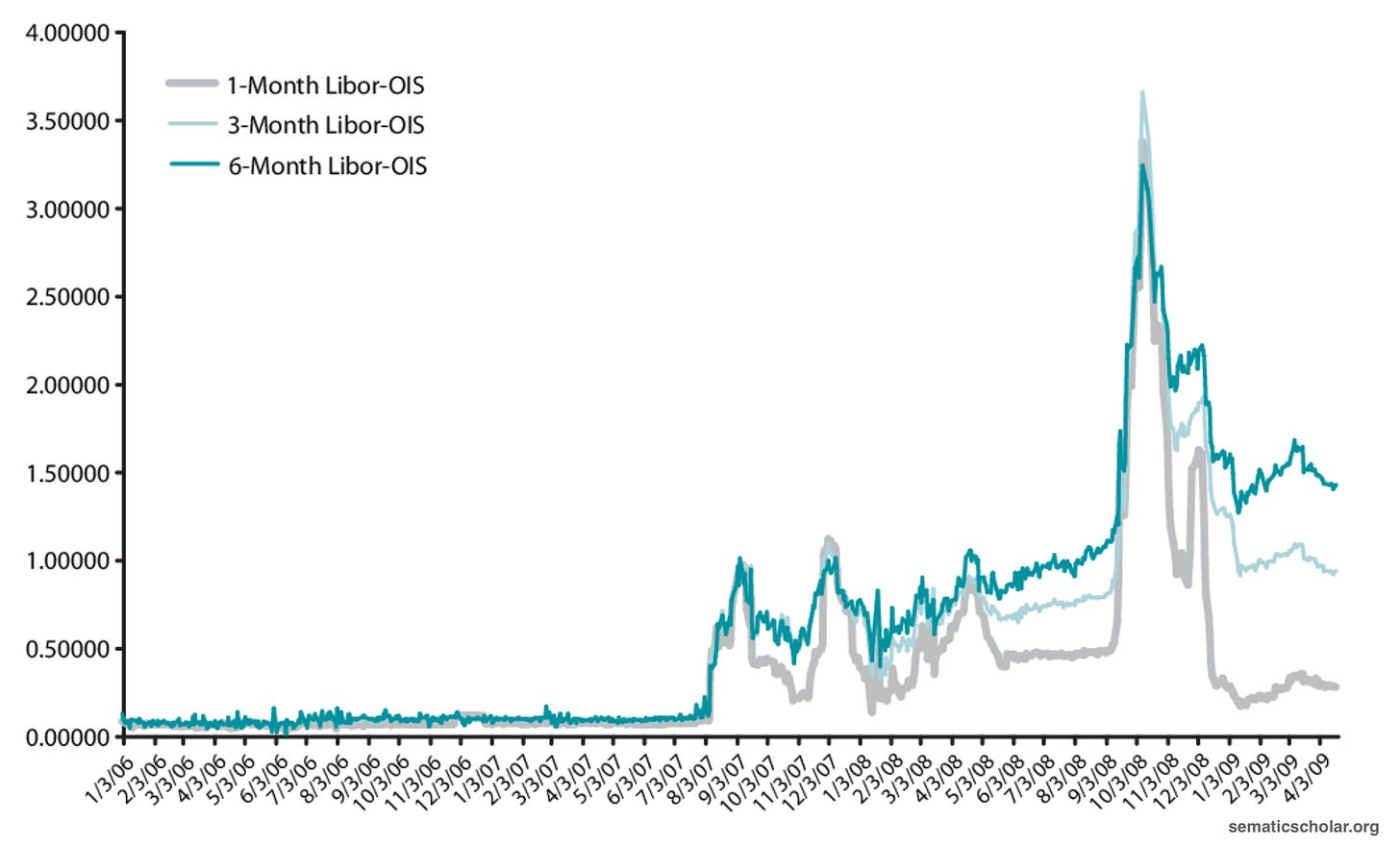

In normal periods, these rates follow each other pretty closely. But in times of stress, like the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, the spread between them widens (banks offering fixed rates want a higher rate to compensate for increased risks of default).

Like so (*note: SOFR used to be LIBOR, and we can get into that another day):

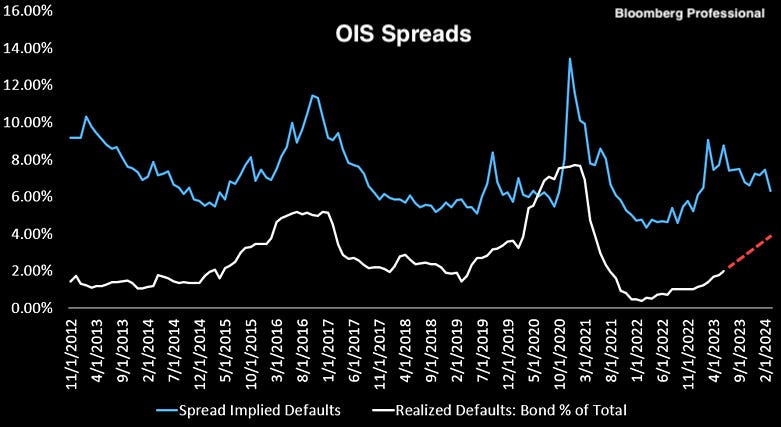

Looking at today’s spreads, Bloomberg is predicting an upturn in defaults, using OIS spreads as an indicator:

Taking it a step further, we can look at high yield bond OAS spreads.

In essence, this shows the difference in yield between bonds rated BB or lower (i.e., high-yield or junk bonds) and the ‘supposedly risk-free’ US Treasury bonds.

As you can see, high yields are hanging in there quite well, but things can escalate quickly.

Bringing it all together:

higher spreads → higher pressure on low quality borrowers → higher default rates → more bankruptcies → possible contagion → severe economic downturn

Next stop: bankruptcies.

😨 Defaults lead to…?

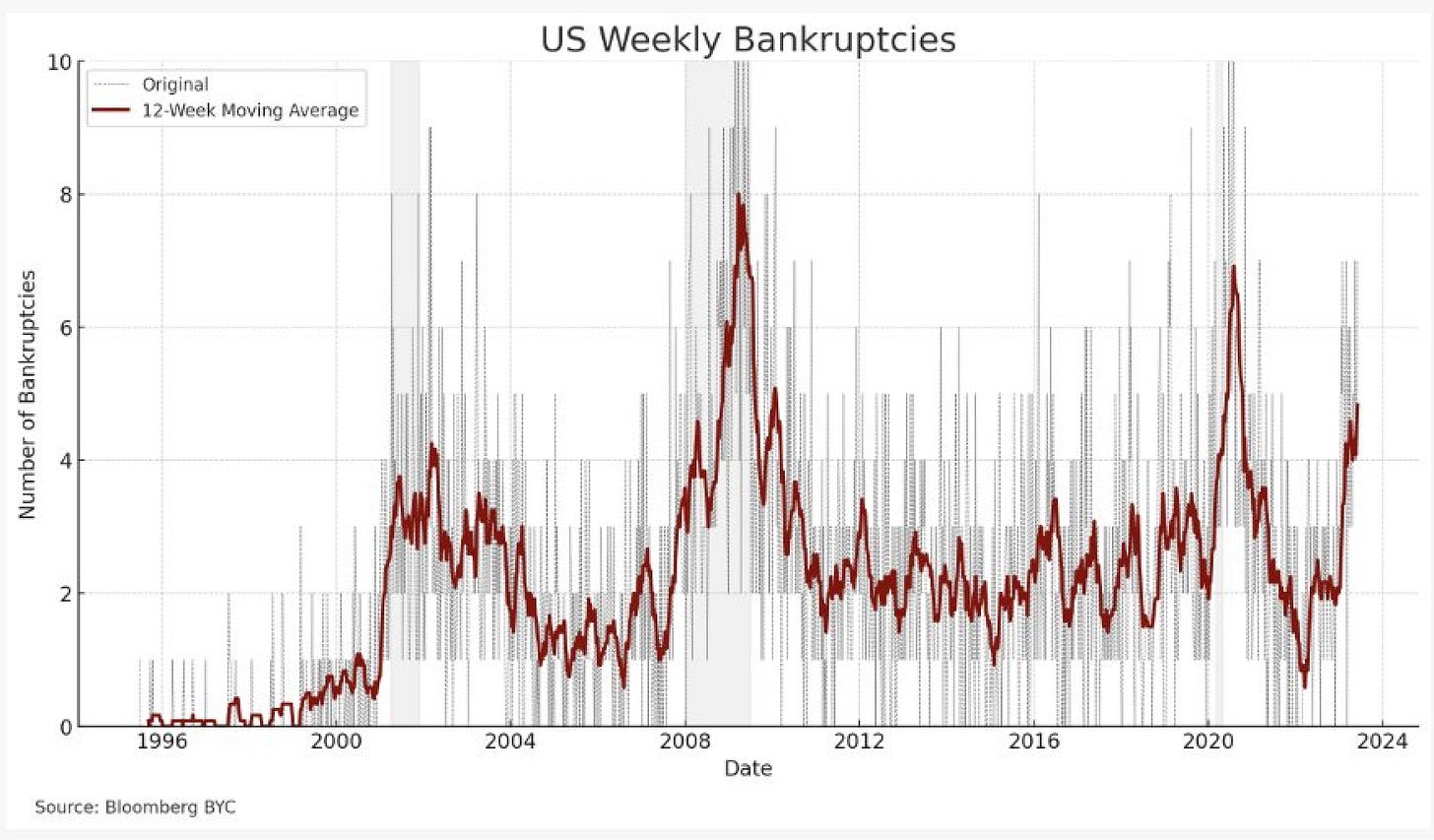

Again, we must not confuse defaults with bankruptcies. But we must acknowledge that many defaults lead to the restructuring or sometimes complete liquidation of companies.

And many companies go bankrupt without ever defaulting on any debt. Simply kaput.

So, how are we doing on this front?

Not so great.

And h/t to @MacroMicroMe for creating a nifty little chart that shows the 12-week moving average of bankruptcies, which helps smooth out short-term fluctuations:

Alarming, to say the least.

🧐 Assume the Position

Ok then, spreads are slowly trending higher, defaults are definitely creeping higher, and bankruptcies are on the rise.

Now what?

Well, the challenge here, IMO, is to first block out the noise (i.e., S&P and NASD driving to new highs on the back of seven AI-related equities), and check your own exposures carefully.

If you’re curious, I wrote all about the Magnificent Seven in a recent newsletter that you can find here:

But for now, looking at the rise of defaults and bankruptcies, we are clearly at risk of entering a cycle of considerable economic contraction. And tactical treatment of portfolio exposures is not just prudent, but a must at this point.

How do you do this?

Well, we are unfortunately at the upper limit for length on this email, and portfolio construction is beyond the scope of today’s subject.

But good news for paid subscribers: I’ve been working on a new feature and will be expanding quite a bit on this very subject in the near future. So, please stay tuned!

In the meantime, I can tell you that I still personally hold a large allocation to FDIC+ insured cash as well as short-term Treasuries and hard monies: gold, silver and Bitcoin.

I also have allocations to certain sector ETFs that I’ve been rotating as we enter this phase of the economy. But like I said, we will get much more into that soon!

That’s it for now. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about defaults and technical defaults and where the credit markets seem to be heading. Before leaving, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest.

And if you’re a paid subscriber, don’t forget to leave a comment or answer a comment in our awesome 🧠 Informationist community below!

Talk soon,

James✌️

Hi James - another great note; especially liked the breakdown of bond covenants and how they relate to defaults. Wishing you and your team a productive week ahead, thank you!

Reading from a dock in Keuka Lake, NY. The Informationist and cup of coffee is best enjoyed at the lake!

Lookin forward to the expanded content for paid subscribers.