Stock Buybacks: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Issue LIV

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox:

Today’s Bullets:

What are Buybacks?

The Good

The Bad

The Ugly

Inspirational Tweet:

With Senators Warren and Sanders calling stock buybacks “nothing more than manipulation” and “stock fluff and buff” (whatever that means), Warren Buffet swiped back, defending his and other companies moves as perfectly good business practice.

But what exactly are stock buybacks, and are they good for companies and shareholders, or just the executives who execute them?

Let’s dig into the good, the bad, and the ugly sides of stock buybacks today, nice and easy as always, shall we?

Equivalent to a weekly double espresso, join to get access to all 🧠Informationist posts + the entire archive of articles

🤨 What are Buybacks?

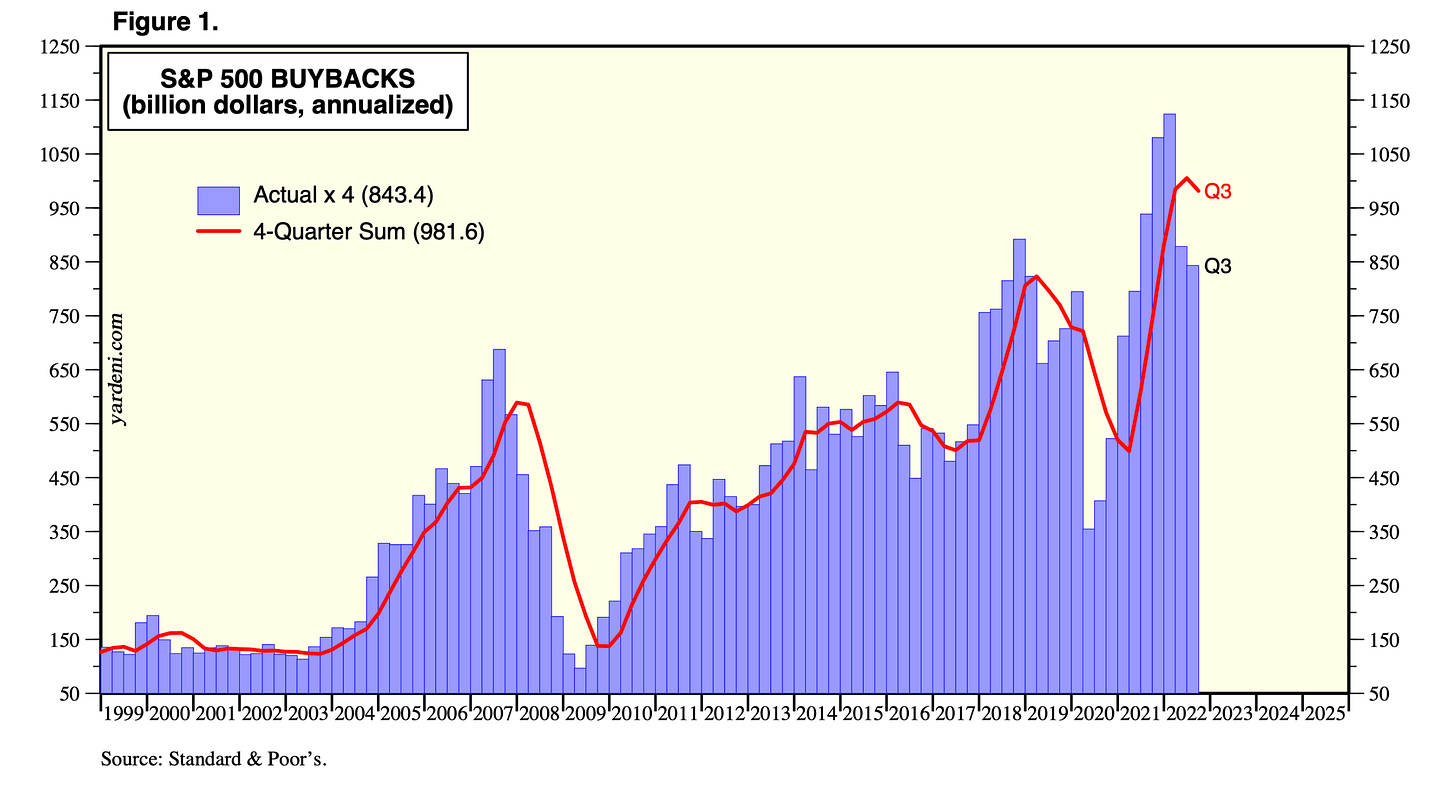

We’ve been hearing quite a bit about share buybacks recently, and for good reason. According to the Wall Street Journal’s calculations, companies are on pace to buy back a record-sized $1 trillion+ of their own stock this year, even outpacing last year’s share buyback bonanza.

For instance, Chevron recently approved a buyback of up to $75 billion, Goldman Sachs announced one for up to $30 billion, and Facebook’s Meta announced a $40 billion authorization.

But at the same time, Goldman and Meta also announced layoffs of over 14,000 employees.

Huh?

Why would these companies use earnings to buy back their own shares instead of keeping their employees and paying them instead? Makes no sense, right?

Or does it?

We’ll get to that. But first, let’s cover how it works, mechanically.

At a regularly or specially scheduled meeting of a company’s board of directors, the board members discuss various ways to optimize their company’s business in order to boost their stock price and thereby please shareholders.

But there is a shortcut to last part, boosting the stock price and pleasing shareholders.

See, if they have the money in their treasury from earnings or they can borrow at a rate that it makes sense for the company’s balance sheet, they can do what we call share buybacks.

Put simply, the board approves a buyback of up to a certain amount its own company’s stock in the publicly traded market. The company uses a broker, like JP Morgan or Citigroup, and gives them parameters to enter the open market (NYSE or NASDAQ) and physically buy the shares at certain prices.

Simple as that.

But going back to the why they would do this, this is where it can get a bit more complicated.

😇 The Good

The simple and often main reason that a company buys back its own stock is to boost the valuation of their shares.

A move like this typically happens when shares are depressed or have had a recent sell off, and the company believes their stock is undervalued in the market. What they are trying to do is boost the stock price by raising the company’s earnings per share (EPS).

It’s possibly the simplest form of financial engineering, and here’s how the math works:

Say Company Z has 100 million shares outstanding and generates $300 million in profits for the year. This means that the company’s earnings per share is $3.

$300 million / 100 million = $3 per share

Now let’s say that Company Z uses some of the cash on its balance sheet to buy back 10 million shares. If the company once again earns the same $300 million, the new EPS calculation is:

$300 million / 90 million = $3.33 per share

By reducing the shares outstanding, they have effectively raised their EPS.

Simple as that.

Taking it a step further, if the market typically attaches a 20X multiple on the shares of Company Z in the market, then the stock would have been trading at $60 before the buyback, but after the buyback, the stock would trade at $66.67.

20 X $3.00 = $60

20 X $3.33 = $66.67

See how that works?

Company Z used its cash to buy stock, and as a result, boosted the price per share for the shareholders. Not a bad deal, eh?

Especially when compared to issuing a larger or special dividend to shareholders instead.

Why?

Dividends are taxed as ordinary income when received. And so, buybacks can delay capital gains taxes until the shareholder actually sells their shares and doesn’t hit them with ordinary tax on a dividend.

OK, all sounds good so far, but as you’ve probably already guessed, there’s more to all this buyback business…

😨 The Bad

As suggested above, sometimes companies issue debt (borrow money) in order to engineer their stock higher. Back to the tax angle, one benefit of this move is that the interest on the loan is tax-deductible.

This is called financing a repurchase and can appear to be brilliant, and absolutely was for many companies that were able to borrow large sums of cash at near-zero interest rates and use it to retire some of their own stock.

However two things: if the company doesn’t have a good credit rating or interest rates are high, the debt payments can drain the cash reserves of the company. This is problematic for a company that is struggling to remain profitable and is using this type of tactic as a last resort move to keep its stock stable or boost it.

Secondly, credit ratings agencies do not look favorably at companies taking on debt in order to engineer their shares higher with stock repurchases. They often downgrade the company’s credit rating in response.

Look at what has happened to Bed Bath and Beyond. Over the last decade, BBBY spent billions in share buybacks, yet those same shares have fallen over 97% since then.

Now, BBBY owes about $2 billion to debt holders, unlikely to ever be paid back and shares a headed to worthless.

Think of what they could have done with all that money to bolster and invest in the business instead. They may actually not be bankrupt.

More on the Bad side, in a new development, President Biden’s so-called Inflation Reduction Act now levies a 1% excise tax on all share buybacks worth over $1 million. So, what was once seen as a tax efficient move is now not as attractive.

And remember, when a company uses its cash to buy back its own stock, it’s not just financial maneuvering to increase shareholder value, there is also an opportunity cost of using of that cash.

After all, the company could have invested in the business itself instead:

It could have bought equipment or other assets or funded research and development in their technology,

It could have been used to grow the company’s business rather than just shrink its shareholder base,

It could have been used to pay employees to be sure they retain their talent and mid-level executives.

Yeah, about that.

Upper executive pay packages (think C-Suite, you know, CEO, CFO, COO, etc…), structured by the board of directors, are usually closely tied to earnings and stock performance.

These are called Incentive Compensation Plans or ICPs.

These ICPs can be in the form of cash bonuses paid out at different stock price and/or EPS levels, and/or straight stock or stock option awards that depend on similar levels.

*Note: You can find these numbers in company filings, often in summary tables, with additional details about the packages in the footnotes. I will warn you though, sometimes they are fairly obscured.

In other words, the board of directors may vote to initiate a stock buyback knowing all too well that this could trigger a windfall of a stock or cash bonus for the CEO or other executives.

Whether intentional or ignorant, the board may be buying back stock with company cash and handing a nice fat—but not obvious to most shareholders—bonus to the executives.

And they can do this without having to approve any new pay packages or bonuses, but rather through simple internal financial engineering. And the vast majority of shareholders would never pick up on it.

Slick, indeed.

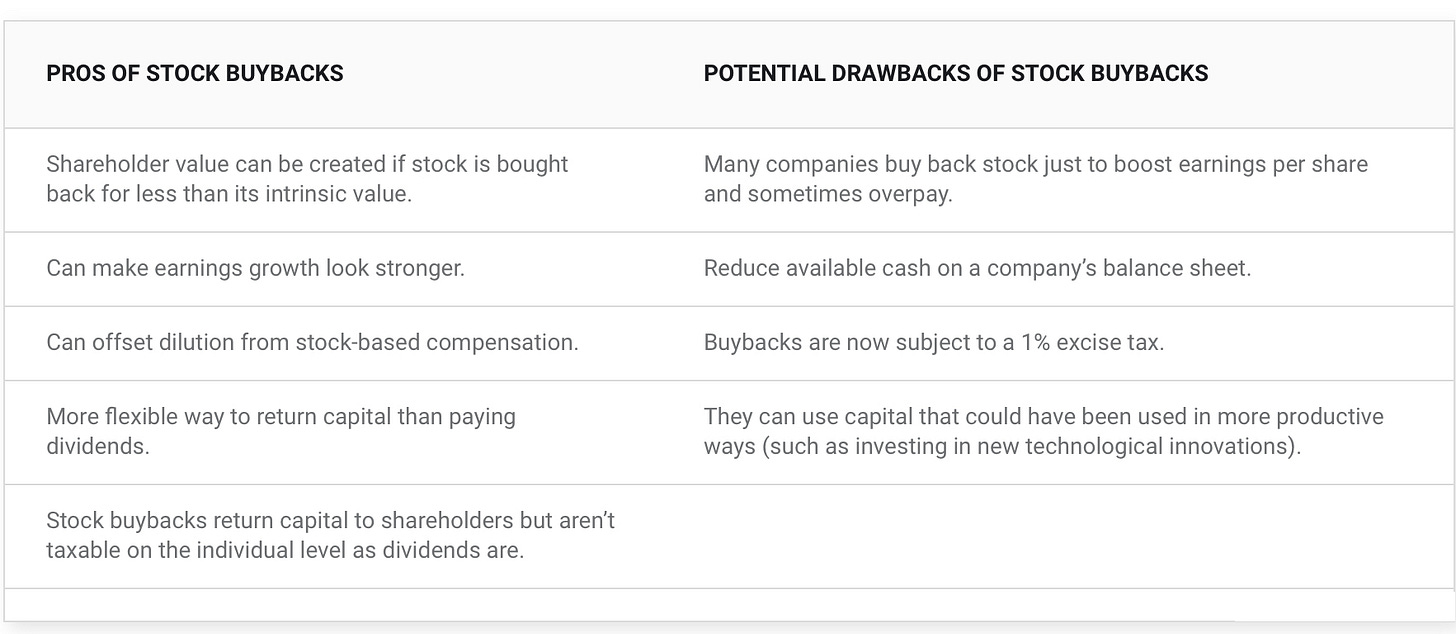

So, to recap the official pros and cons of stock buybacks:

Ah, but there is yet another angle we need to cover. And it’s ugly.

😈 The Ugly

Sometimes companies will approve and execute share buybacks, and instead of retiring those shares and boosting the stock price for shareholders, they keep them in the company treasury instead.

But, what’s the point of that?

Let’s turn back to those generous ICPs for some answers.

Remember, there are three main ways to reward executives that the board of directors believe deserve it:

They can award the executives a cash bonus, straight from earnings—obvious to pretty much everyone in and outside the boardroom, this opens the board up to serious scrutiny,

They can award stock options as incentive to drive performance higher, which at least has the appearance of executive incentives being aligned with shareholders’ interests, but is not quite as attractive to the executives themselves, it makes them work that much harder for it, and if the options are in-the-money (already worth something) it opens up the board to scrutiny again,

Or they can just award straight stock to the executive, diluting shareholders and making each share of stock worth less, and this would bring straight heat to the board from angry shareholders

See, if the board awards straight stock to the executives, then it has the effect of diluting shareholders ownership of the company. Going back to the example above, let’s stay that Company Z issues 10 million more shares instead of buying them back.

$300 million of earnings / 110 million shares = $2.73 EPS

Hmmm. Shareholders won’t like that.

So, what can the board of directors do instead?

Well, they can use the cash from earnings to institute a share buyback, stuff the company treasury with shares, then instead of retiring the shares and boosting the stock, they can turn around and hand those shares to the C-Suite in nice, big, fat bonuses.

They effectively used the company’s cash to buy shares and then handed them to the oh-so-deserving executives.

What a deal. And pretty much obscured to the general population of shareholders.

Ugly, indeed.

So, there you have it. If a company executes a well thought out and planned share buyback, it can be a great use of their cash, boosting the stock price and indirectly creating value—without triggering a tax event— for shareholders.

But sometimes this move comes with an opportunity cost.

Sometimes it’s done as a last resort, using expensive debt.

And sometimes it’s done to obscure huge windfalls of bonuses to C-level executives who are often golf and hunting and sailing buddies with the very members of the board who are engineering and approving the bonuses, obscuring a raid of the company treasury all for themselves.

And we wonder why so many of these executives own private jets and yachts.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about stock buybacks and the good, the bad, and the ugly uses of them.

Before leaving, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest. And if you’ve found The Informationist to be valuable, or just want to support the work I’m doing, consider subscribing. It would mean a ton to me. 🙏

✌️Talk soon,