💡SLR: Why Banks are Warning The Fed

Issue 168

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today’s Bullets:

The SLR and its History

ISDA and its Recommendation

What it All Means for Banks

Inspirational Tweet:

The SLR or Supplementary Leverage Ratio sounds like yet another boring banking detail that pretty much nobody but financial super-geeks would or should care about.

Nothing could be further than the truth.

Because the SLR underpins not just bank holdings, but the sheer amount of US Treasuries that the US government may be able to float in the near future.

How?

Well, ratios and regulations can be confusing, but have no fear, we will unpack the SLR and much more—all super simply as always—today.

So, pour yourself a nice big cup of coffee and settle into your favorite comfortable chair for a peek behind the bank regulation curtain today with The Informationist.

Partner spot

America's Most Secure Mobile Service

Really quickly and before we start, I cannot stress this enough. If you’re not protecting yourself from cyber attacks and SIM-swaps, you’re at serious personal risk these days. After seeing four of my colleagues go through the nightmare of SIM-swaps (someone literally taking control of your phone from afar)—identities stolen, bank accounts compromised, emails hijacked, social media held for ransom—I knew I was at risk, too.

So, I switched to a service called Efani, and it was super easy and seamless. It feels just like being with Verizon or AT&T, but I can rest easy knowing that my phone is ultra-secure. My colleagues learned the hard way, but now we’re all on Efani, and I couldn’t be happier. I honestly wouldn’t share this with you if I didn’t completely believe in the service myself. Whether you use Efani or something else, please don’t wait until it’s too late to protect yourself.

And if you choose Efani by using the link below, you get $99 OFF.

The Efani SAFE plan is a bespoke cybersecurity-focused mobile service protecting high-risk individuals against mobile hacks, providing best in class protection with 11-layers of proprietary authentication backed with $5M Insurance Coverage. Don’t wait. Protect yourself today.

🤓 The SLR and its History

The Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) is one of the most impactful regulations in the post-2008 Great Financial Crisis banking world.

Designed as a simple capital measure to prevent too much leverage, the SLR has become a central choke point in the financial system’s ability to absorb US Treasuries, manage reserves, and act as a liquidity shock absorber.

In a world where the US is issuing trillions in additional debt each year, the Fed is reducing its balance sheet, and the primary dealer system is under stress—the SLR is at the heart of whether banks can absorb the much needed liquidity.

But what exactly is this SLR?

In the most basic terms, the SLR is a calculation of leverage that includes all assets on a bank’s balance sheet.

Problem is, the SLR doesn’t care what kind of asset a bank holds, it just counts it all as risky.

Here’s the formula:

SLR = Tier 1 Capital / Total Leverage Exposure

Where:

Tier 1 Capital = Bank’s common equity and retained earnings.

and Total Leverage Exposure includes:

All on-balance-sheet assets (Treasuries, loans, reserves, cash, etc.)

Off-balance-sheet exposures (letters of credit, undrawn loan commitments)

Derivative exposures

Repo and reverse repo agreements

The minimum required SLR is:

3% for most large institutions

5% for G-SIBs (Globally Systemically Important Banks, aka too big to fail)

6% for their insured depository subsidiaries

That may sound manageable, but for a trillion-dollar balance sheet, every 1% requires $10 billion in equity capital—not something most banks can just conjure overnight.

So, where did the SLR come from, and why?

In essence, the Global Financial Crisis (2008) exposed massive blind spots in the banking system’s capital framework. Before the crisis, banks simply piled on assets that looked “safe” under risk-weighted frameworks—think AAA-rated mortgage-backed securities.

But when those collapsed, capital buffers were exposed as entirely inadequate.

In response, Basel III (a set of global banking rules created by international regulators and named after the Swiss city where the rules were developed) introduced the SLR to ensure that banks couldn’t avoid leverage constraints by somehow gaming the risk-weighting system.

A little Basel history:

2010–2013: Basel Committee proposes and refines the SLR

2014: US banks begin reporting SLR publicly

2018: SLR becomes binding for G-SIBs, who must meet higher thresholds

The idea was perhaps too simple: even if a bank holds supposedly super safe assets (i.e., US Treasuries), it still needs real equity to back those positions.

Make you wonder how safe US Treasuries really are, doesn't it? 🤔

And so, the SLR now clashes with monetary policy and real-world market dynamics.

Why?

Because as far as the SLR is concerned, banks reserves and US Treasuries are just as risky as a mortgage-backed security or even shares of NVIDIA. 🤡

Example: JPMorgan in 2021

JPM’s deposits ballooned during the COVID crisis, as The Fed flooded the system with liquidity. But that meant more bank reserves at the Fed, which counted against SLR capacity.

CEO Jamie Dimon warned:

“We’ve stopped taking certain deposits not because we don’t want them, but because we can’t hold the capital.”

That’s back-ass-ward: banks should welcome all deposits and be rewarded for holding safe assets—not punished.

And so, in March 2020, the US Treasury market—the deepest and most important market in the world—simply broke down. Bid-ask spreads widened, bond prices fell as investors sold to raise cash, and banks did not step in to buy.

Why? Their SLRs were maxed out.

Even though they had capital and wanted to provide liquidity, doing so would have triggered regulatory penalties or forced them to raise new equity.

The Fed had to step in with:

Over $1.5 trillion in repo operations (lending dollars for USTs)

A temporary SLR exemption (removing USTs and reserves from the denominator)

A return to massive QE to absorb the onslaught of US Treasury issuance

The temporary exemption ended in March 2021, under pressure from lawmakers who were worried of a repeat of the GFC someday.

And the Big 6 Banks have been under pressure ever since.

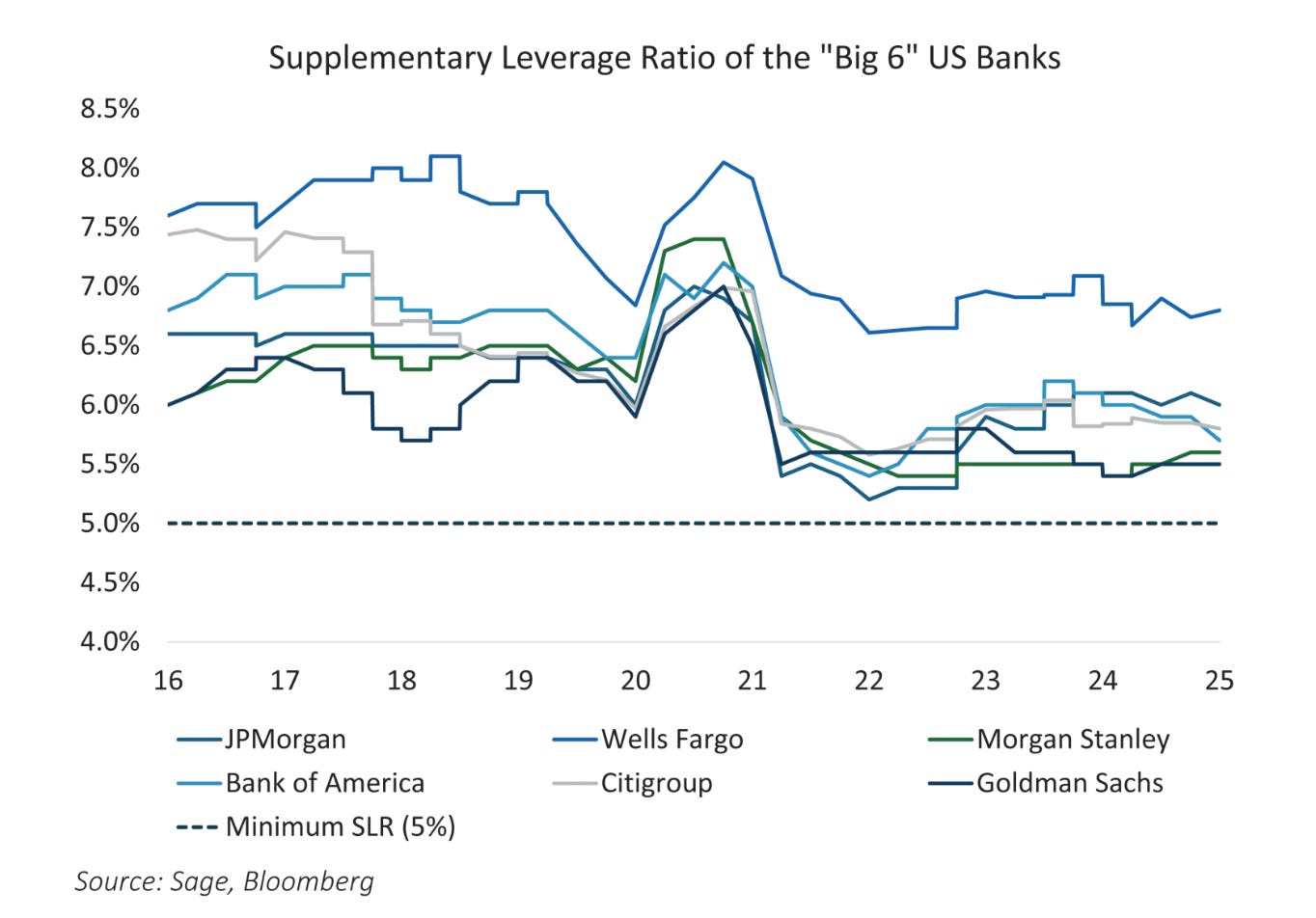

What we see here is how the SLR at the six major US banks fell during 2020–2021 — when assets like reserves and USTs ballooned—and then when the exemption ended, it reintroduced pressure on balance sheets.

Banks reacted by reducing market-making, tightening repo lending, and positioning much more defensively.

And this has created something of a problem not just for banks, but for the Fed and the US Treasury itself.

Which is exactly what ISDA and bank leaders are now trying to fix.

🔍 ISDA and its Recommendation

Here's the thing.

As US debt issuance continues to grow (regardless of what the DOGE commission seeks to accomplish—akin to removing a few deck chairs off the Titanic), the Fed continues to reduce its balance sheet through QT, and liquidity in the Treasury market becomes more fragile, the banking system is being asked to absorb a growing burden.

But now, banks aren’t positioned to respond—not because they don’t have the capital, but because of how capital rules are structured.

As a result, the SLR is drawing renewed scrutiny, especially from ISDA, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

You may now be asking, what is ISDA?

I’ve written all about ISDA before, but for those new around here or if you need a refresher, let’s quickly recap.

Founded in 1985, ISDA rapidly became the global standard-setter for the derivatives market, developing the ISDA Master Agreement, a legal framework that governs trillions of dollars in swaps and derivatives.

Today, ISDA represents over 1,000 member institutions across 79 countries, including:

Global banks

Central counterparties (CCPs)

Asset managers

Insurance firms

Law firms

Technology vendors

In short: ISDA is where regulators and market participants meet. ISDA writes the legal language that governs market plumbing. They comment on every major capital, liquidity, margin, and trading rule.

And while ISDA doesn’t write law, regulators listen to their recommendations—because they reflect not just banks’ interests, but the operational and legal structure of the financial system itself.

Why does this matter?

One year ago, in March 2024, ISDA submitted a formal letter to The Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the FDIC, urging a specific change to capital requirements:

Exclude US Treasuries from the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR)

They wrote:

“While the leverage ratio is intended as a non-risk-based backstop to risk-weighted capital measures, its current calibration and broad scope reduce banks’ capacity to act as intermediaries — especially in the US Treasury market — during periods of market stress.”

ISDA noted several problems:

SLR disincentivizes banks from holding Treasuries, despite their supposedly risk-less nature

In March 2020, the Treasury market froze partly because SLR rules prevented banks from stepping in to buy

Temporary relief granted by the Fed during COVID worked — exempting Treasuries and reserves helped stabilize markets — but that expired in March 2021

They added:

“A more risk-sensitive leverage framework is essential for promoting market resiliency and financial stability.”

Jamie Dimon enters the chat.

Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, Dimon has been a huge critic of the SLR, and in his 2024 annual letter to shareholders, he said:

“Current capital and liquidity requirements, including the SLR, are overly conservative and constrain our ability to serve clients and support markets.”

He continued:

“We should not penalize banks for holding cash and US Treasuries—the safest and most liquid assets in the world.”

Dimon has warned that JPMorgan may limit deposit-taking, reduce market-making, and pull back from repo operations if balance sheet capacity continues to be constrained by SLR rules.

And it’s not just Dimon—Brian Moynihan (BofA), Jane Fraser (Citi), and Goldman Sachs execs have all echoed similar concerns recently.

Put it this way, when CEOs of G-SIBs begin shaping the narrative, regulators listen (read: heel)—especially when they back it with hard data and system-level arguments.

So why does the Fed care?

Because the Fed needs banks to act as liquidity providers, especially in Treasury and repo markets, and the SLR makes that nearly impossible in times of stress—because every dollar of Treasuries or reserves eats into a bank’s leverage capacity.

A 2022 Fed Staff Paper said:

“The SLR can become binding at precisely the wrong moment…When reserves and safe assets rise, it restricts balance sheet capacity rather than expanding it.”

That’s why:

In 2020, the Fed gave banks a temporary exemption from counting USTs and reserves in the SLR

But it let that exemption expire in March 2021 under political pressure—as DC geniuses like Elizabeth Warren argued that it was a “gift to Wall Street”

Now in 2024, with relentless deficits that lead to more Treasury debt issuance and continued QT, we’re right back where we started—but likely with much higher stakes.

To underscore the problem, ISDA cited the March 2020 Treasury market seizure, when:

Foreign holders dumped USTs for dollars

Bid-ask spreads in Treasuries widened dramatically

Banks didn’t step in—not because they didn’t want to, but because SLR caps prevented them from doing so

It took the Fed launching $1.5 trillion in repo operations and temporarily suspending the SLR rules to prevent an all-out US Treasury market meltdown.

To be clear: this wasn't a credit default event—it was a regulatory requirement failure.

And now ISDA and the banks are warning the Fed to not let it happen again.

They aren’t demanding a total rewrite of capital rules. They’re proposing a simple fix: Exclude US Treasuries from the SLR denominator.

This would:

Allow banks to absorb more Treasuries during crises

Improve repo market depth and Treasury auction stability

Reduce reliance on the Fed for emergency liquidity injections

Bottom line. ISDA’s recommendation is about removing a chokepoint that grinds the system to a halt right when liquidity is most needed.

And with Jamie Dimon and other industry leaders vocally backing the move, it’s rapidly gaining momentum.

The question now is whether the Fed, OCC, and FDIC are willing to not just listen, but revise the rule accordingly.

If they do, Treasury market resilience will improve.

If they don’t, then when the next shock arrives—this is a when, not an if, BTW—the Fed will ask itself a familiar question: why didn’t we address this sooner?

✍️ What it All Means for Banks

It's clear, the SLR is more than a technical constraint.

It's a macro-critical gatekeeper that shapes whether banks can handle liquidity needs and perform their role as shock absorbers in a system increasingly reliant on them.

But what does that actually mean for banks, Treasury markets, and the financial system going forward?

Let’s break it down.

Under current SLR rules, banks are penalized for holding:

US Treasuries, which are credit risk-free

Reserves at the Fed, which are literally cash

Repo exposures, which are short-term collateralized loans usually backed by US Treasuries

These are the most liquid, (supposedly) safest instruments in global finance—and yet they constrain a bank's ability to operate.

If USTs are excluded from the SLR denominator, banks immediately gain:

More capacity to absorb Treasury supply

More room to accept deposits

More freedom to engage in repo financing

This doesn’t just benefit banks—it stabilizes the core funding markets of the U.S. financial system.

What it means for the repo market.

Banks often pull back from repo lending during stress because repo trades use balance sheet space that counts against SLR

This can cause spikes in overnight rates, especially around quarter and year-end when banks try to manage optics for regulatory filings

During periods of Treasury issuance surges or volatility (like the March 2023 SVB panic), this constraint exacerbates instability

Removing Treasuries from the SLR could:

Deepen repo liquidity

Reduce reliance on Fed facilities like the Standing Repo Facility (SRF)

Allow for more natural dealer intermediation without triggering bank penalties

And of course, most importantly, US Treasury market liquidity will likely dramatically improve.

How?

With over $36 trillion in US debt outstanding—and over $2.5 trillion more issued each year—the Treasury market’s continued functioning is essential to:

Government funding (also known as relentless fiscal deficits)

Monetary policy implementation

Global ‘risk-free’ pricing

Yet multiple 100-year events (March 2020, Sept 2019 repo crisis, even the March 2023 regional bank fallout) have shown that the US Treasury market is not invincible.

Removing Treasuries from the SLR:

Increases bank willingness to bid at auctions

Reduces the need for the Fed to buy Treasuries indirectly (through QE or other silly acronyms like the BTFP, Bank Term Funding Program to save regional banks after Silicon Valley Bank collapsed)

Strengthens the public-private partnership at the heart of US debt financing, i.e. banks and hedge funds borrowing and lending around US Treasuries

Ok, so what about the banks themselves? How do they benefit from SLR changes?

For large institutions like JPMorgan, Bank of America, and Citi, SLR reform would:

Unlock hundreds of billions in balance sheet capacity

Reduce pressure to tiptoe around capital restrictions

Encourage additional UST market-making, repo lending, and primary dealer activity

Right now, banks are forced to play defensive regulation arbitrage:

They reject low-cost deposits to avoid more reserves

They rotate out of Treasuries to free up leverage headroom

They reduce secured lending to avoid capital penalties

In truth, this isn’t risk management. It’s capital inefficiency caused by a blunt tool.

And it makes the system less safe.

And what if regulators fail to act? What could happen?

I can think of a few things:

Market Fragility Increases

Treasury auctions eventually become more volatile. Bid-to-cover ratios decline. Liquidity dries up during periods of stress.The Fed Becomes the Buyer of Last Resort Again

Without balance sheet space in the private sector, the Fed may be forced to implement emergency and massive QE—reigniting unintended inflationary forces.Shadow Bank Substitution

If banks are constrained, non-banks (hedge funds, PE-backed credit firms) will likely step in—without the same regulatory oversight—which simply moves risk to the shadows.Global Spillover Effects

The US Treasury market is the foundation of global collateral. If its liquidity becomes unreliable, US dollar funding markets worldwide could seize up, as they did in 2008 and 2020.

There’s an ironic twist here.

If regulators exclude US Treasuries from the SLR—recognizing them as a special, systemic class of collateral—they effectively elevate Treasuries to a “super-sovereign” status within bank balance sheets.

That strengthens their role as:

The global store of value (SoV)

The ultimate collateral instrument

The core transmission mechanism for monetary policy

But it also raises a larger question: if US Treasuries are only liquid and safe when rules are changed to make them so, what does that say about their future role in a higher-debt, higher-rate world?

And what does it mean for true Store of Vale (SoV) assets like Bitcoin, which don’t rely on central bank carve-outs to function?

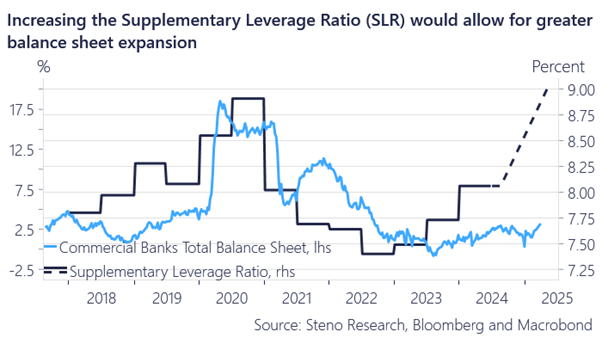

In the end, the removal of US Treasuries from the SLR effectively allows for banks to expand liquidity ad infinitum.

Remember: expansion of liquidity is rocket fuel for true SoV assets, like Bitcoin.

And Bitcoin is the ultimate long-term beneficiary of this new financial world structure: one where there is zero constraint on the expansion of liquidity.

And so, instead of having yet another shock to the US Treasury market and another blast of liquidity from the Fed’s money bazooka, we will see the constant and relentless expansion of money supply instead.

What a world to be in, if you own some Bitcoin.

The only asset that cannot be manipulated and debased. My personal asset of choice to own in this oh so Brave New World.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about the SLR and how it affects banks, the Fed, and you.

If you enjoyed this free version of The Informationist and found it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️

Nice tie into Bitcoin. I understood about 90% of your discussion but 100% understood it’s bullish for the coin! Thank you James!

Another great article, James... Nice work!