LDIs and the UK Pension Meltdown

Issue XXXVII

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox:

Today’s Bullets:

Pension funds

LDIs and leverage

London, we have a problem

Where does this leave the UK?

Inspirational Tweet:

You’ve heard the term LDI and seen in the news how they nearly took down the entire UK pension fund system. But what is an LDI, and how did they cause an emergency that forced the Bank of England to save their pension funds?

Let’s get it all sorted out nice and easy, as always, as we answer these questions and more for you here today.

🤑 Pension funds

First of all, a pension fund or scheme, as they’re called in the UK, is an investment vehicle that pays an income to its members when they retire. This is money that the fund effectively owes its members. The total amount owed is set up as a long series of payments that can stretch far into the future.

To put it simply, these future payments are liabilities to the fund.

Hence, the fund will project a schedule of aggregated monthly or annual payments the fund is expected to have to make over its lifetime. By assembling necessary member data (employees who are owed the future salary payments), such as years worked, average salary, rate of accrual and age, the fund’s actuary calculates the estimated cashflow projections for the lifetime of the fund.

In the example created by BMO below, each bar represents how much must be paid for every year over the life of an example fund. You can see liabilities peak in about 30 and 35 years, when the fund will need to provide the highest amount of annual payments.

Bottom line, the fund needs to project these payments and then find a way to create enough growth and income in their investments in order to meet these expected obligations. Two factors that are major contributors to this estimate are interest rates and inflation.

Higher interest rates mean that the fund can assume a higher rate of return on investments to meet these obligations, lower rates mean they must assume a lower rate of return.

The discount rate.

However, the discount rate is adjusted by inflation to create a real discount rate. And higher inflation means a lower real discount rate (or a lower assumed return on their investments).

You see where we are going with all this, right?

Exactly.

With perpetually low interest rates this past decade, pension funds have had a difficult time generating enough return on its investments to meet the expected future payments to the pension members.

Enter leveraged Liability Driven Investments or LDIs for short.

🤫 LDIs and leverage

Liability Driven Investments are not necessarily problematic in and of themselves. As stated above, pension fund managers have estimated future liabilities. They must find a way to meet these.

In essence, an LDI has two basic objectives:

First, the LDI is meant to generate returns from opportunities available in the market, such as equity or debt investments. The second objective is to manage or minimize risks from investments. These risks can be changes to interest rates or fluctuations is currencies, if investments are global, etc.

To minimize risks like these, an LDI will have a hedging component to neutralize that effect on the portfolio. How do they do this?

Swaps and derivatives.

I.e., the fund swaps a variable interest rate for a fixed interest rate or exposure to a foreign currency to a denomination in the fund’s native currency.

Simple, right?

Well, that is unless interest rates and expected returns from bonds remain ultra low, and risk management only allows a maximum allocation to higher return (higher risk) securities for the fund.

See, with ultra low, and/or falling interest rates over the past decade (or more), many funds were struggling to keep up with the necessary returns to fund their future obligations (liabilities). Bond investments, while super consistent and stable during those years, offered anemic returns for funds. This meant funds had to either raise their allocations to higher-risk equities or other risk assets, or employ other tactics to solve this liability math problem.

Enter leverage.

By employing leverage on the lowest perceived risk assets of their portfolio, bond investments, funds were able to generate multiples of returns that they would normally receive from those bond investments.

How:

Buy bonds using swaps and derivatives → post a fraction of underlying investment as collateral → receive return that is multiples of a non-leveraged investment

A fantastic strategy, up until it isn’t.

😱 London, we have a problem

Like we said, all was seemingly going fine for UK pension funds employing the above leveraged LDI strategy. They had their estimated obligations or liabilities, they had their expected return on available assets, and they used LDIs to hedge out certain risks then leverage up those investments to generate enough return to meet their obligations.

But then a few developments began to impact this strategy quite negatively.

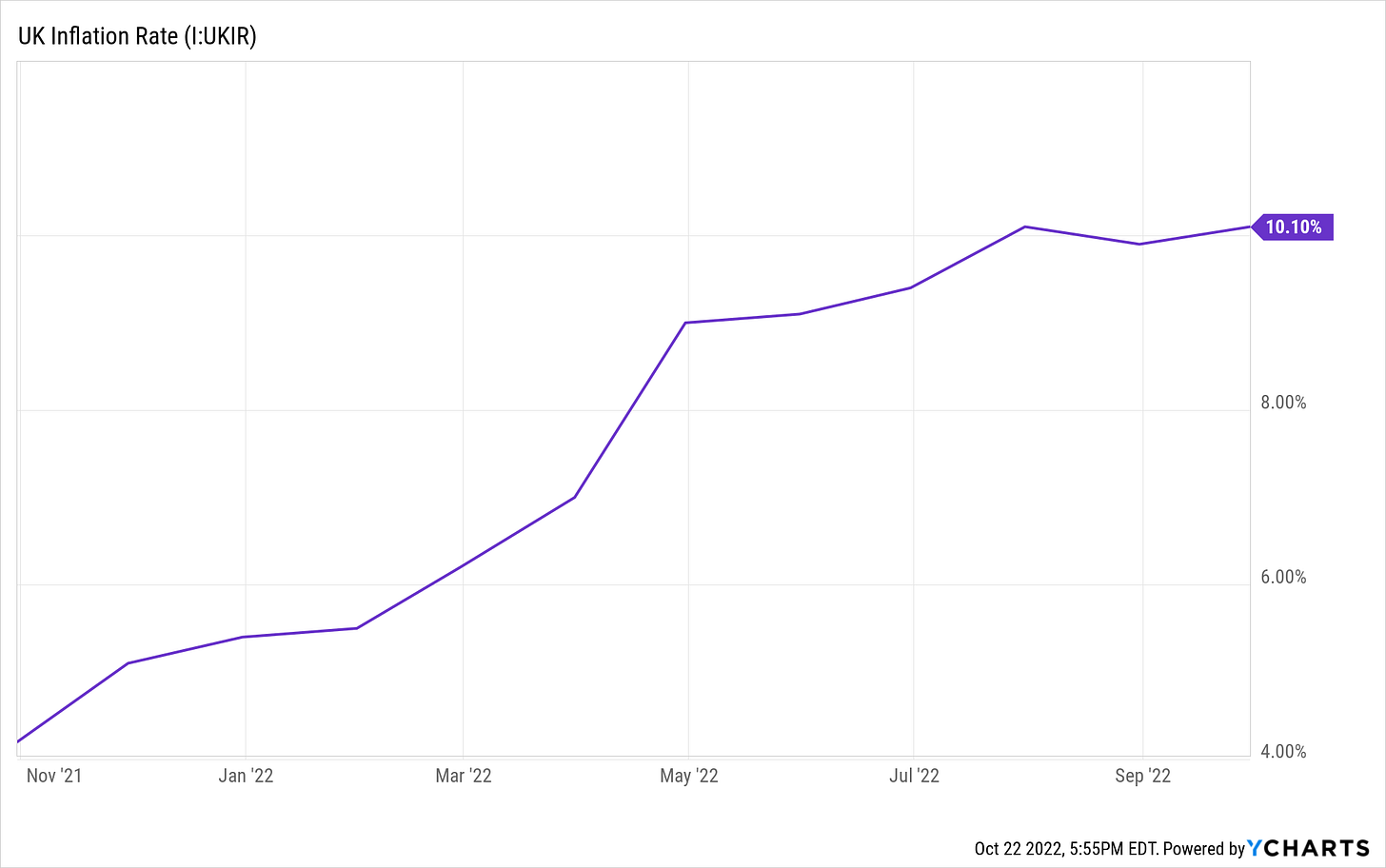

First, inflation has been through the roof for the UK, reaching 10% at the last measure and raising the bar significantly on UK pension schemes (funds) to generate returns to match the now severely elevated obligations, while only being offered seriously negative real returns by bonds.

The Bank of England, in response, began to raise interest rates.

Then everything suddenly went sideways for the UK.

First, newly appointed Finance Minister Kwasi Kwarteng announced a massive surprise tax cut, including cutting the top rate of income tax, as part of the biggest package of tax cuts in 50 years.

The British pound and UK gilts (government bonds), already under pressure, crashed almost instantly.

The gilts, in particular, became problematic for UK pension schemes, as when they collapsed in value, they pushed through levels that generated margin calls by the banks who had extended all that leverage to them.

Remember, when you make an investment using leverage and the investment falls enough in value, you are obligated to send more money (collateral) to keep the position. Otherwise, the lender will sell the position to protect their own invested capital in the swap.

You got it.

The over-levered pensions almost immediately received margin calls, and some of them sold positions in gilts to generate cash to meet those calls. And it all snowballed in a single day. With many funds selling at once, gilt prices fell, yields were pushed even higher, and this in turn increased the collateral payments they already needed to make.

These dominoes started to cascade and threatened a meltdown of epic proportions.

And so, while at the same time they are raising interest rates to tame inflation, the Bank of England stepped in to buy UK gilts and save the market before it went nuclear.

This is the same as putting more cash into the system, and whether through emergency measure or not, it is essentially a form of QE. Meanwhile, the situation also forced the BOE to delay planned bond sales off their balance sheet.

So much for QT and tightening to fight inflation.

And the result? Prime Minister Liz Truss fired Finance Minister Kwasi Kwarteng, and then, amidst the turmoil and just six days later, resigned herself.

*Note: markets really dislike complete and massive surprises.

🤭 Where does this leave the UK?

And now, as you can see, the UK sits in a tenuous position.

Not politically, they’ll fill those gaps with more fiat-driven, closed minded lifers.

What I mean is, the BOE is in a battle against rising and stubborn inflation. At over 10%, this threatens serious negative impacts to the economy. If the BOE can’t tame inflation, it could just spiral out of control.

Meanwhile, the pound and gilts, while stabilized, are still showing signs of weakness, particularly in the liquidity of gilts.

And if we circle back around to the original Twitter post from Dylan above, this all demonstrates just how fragile our entire system built upon mountains of debt has become.

With these massive amounts of debt on sovereign balance sheets and central banks raising rates in response to rising and stubborn inflation, we are starting to see the results of relentless over-manipulation.

Re: the comment quoted in Dylan’s post: “Next in line could be the European sovereign bond markets,” it is undeniable that the cracks are beginning to show. And just like LDIs and UK pension schemes, Europe has a major imbalance of debt (liabilities) and revenues.

Namely Germany and Italy, today.

I’ve written about these issues recently, and if you want a bit more detail of what may be ahead, you can find much more in this recent Informationist article:

For the TL;DR crowd, I believe Europe has deep financial problems structurally, and will ultimately break up over them within the decade.

So, be careful out there, investors, and don’t be afraid of holding some cash and owning hard monies like gold and Bitcoin to weather the storms and capitalize on the eventuality of further and exponential expansion of the global fiat money supply.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about LDIs, the UK pension scheme system, and the challenges the UK and BOE are currently facing.

Before leaving, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest. And if you want daily financial insights and commentary, you can always find me on Twitter!

✌️Talk soon!

James