Can a Treasury Auction Fail?

Issue 111

✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🫶 If this email was forwarded to you, then you have awesome friends, click below to join!

👉 And you can always check out the archives to read more of The Informationist.

Today's Bullets:

Auction Terms and Basics

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Total Fail

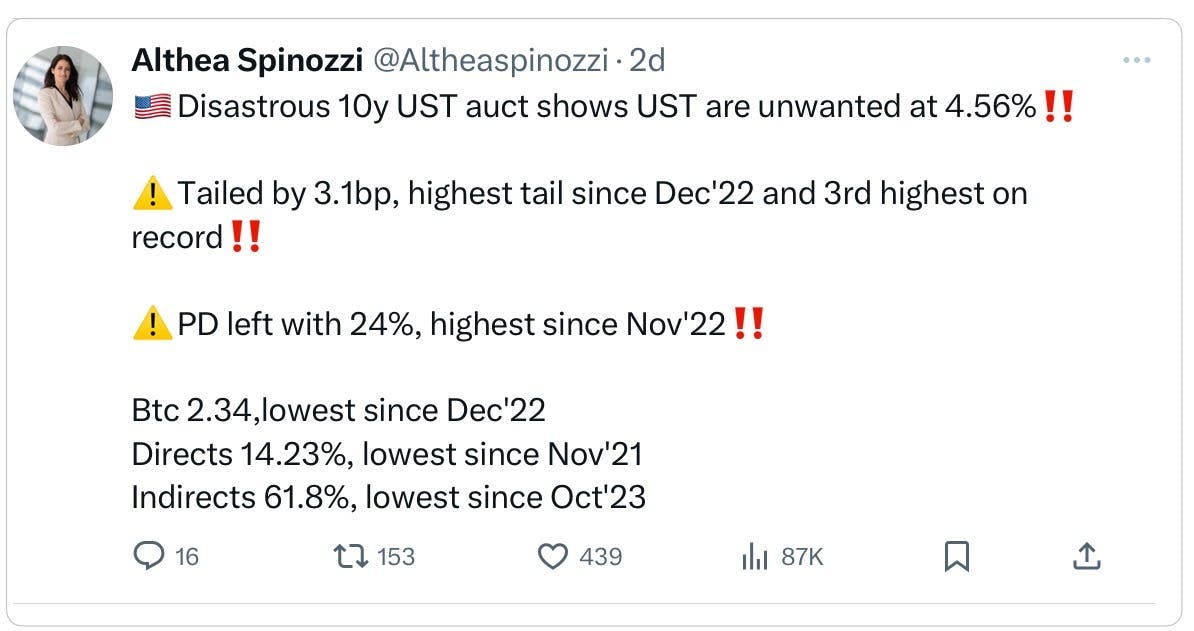

Inspirational Tweet:

Huge tail! Low BTC! Primary Dealers hit with 24% of the auction! Disastrous!

Is this true? Was last week’s 10YR US Treasury auction an all-out disaster? Or is it just Twitter/X hyperbole? Doom porn, as the kids now call it.

Fair and important questions in this day and age, especially with current the economic uncertainty out there.

Spoiler Alert: I don’t consider Althea a doom and gloom attention seeker, and this post is (mostly) spot on. But that said, and most importantly for our purposes here at The Informationist, you may be sitting here wondering…

What does it all mean? And…how do you read auction results to know for yourself?

Well, we are going to answer all that and more here today, riffing off an older issue posted last year, with some important updates.

Why?

Quite simply, and to reiterate, it is super important and well worth a re-visit or initial understanding of how Treasury auctions work. But have no fear, we keep it simple and clear around here, with the main goal of making you smarter.

So, grab your favorite cup of coffee, settle into a comfortable seat, and let’s get bond busy with The Informationist.

👋 Auction Terms and Basics

What we’re talking about here today are auctions hosted by the US Treasury to sell bonds in order to finance the public debt.

Treasuries are named according to their term (length of maturity):

Treasury Bills (T-Bills) have terms shorter than 1 year

Treasury Notes (Notes) mature anywhere from 2 to 10 years

Treasury Bonds (just Bonds) typically have maturities of 20 to 30 years

and then there are Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) and Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) with various maturities

*Some slang clarification. These can all be referred to as *Treasury Bonds*, but traders never refer to anything longer than 10-year maturity as a *Bill* or *Note*.

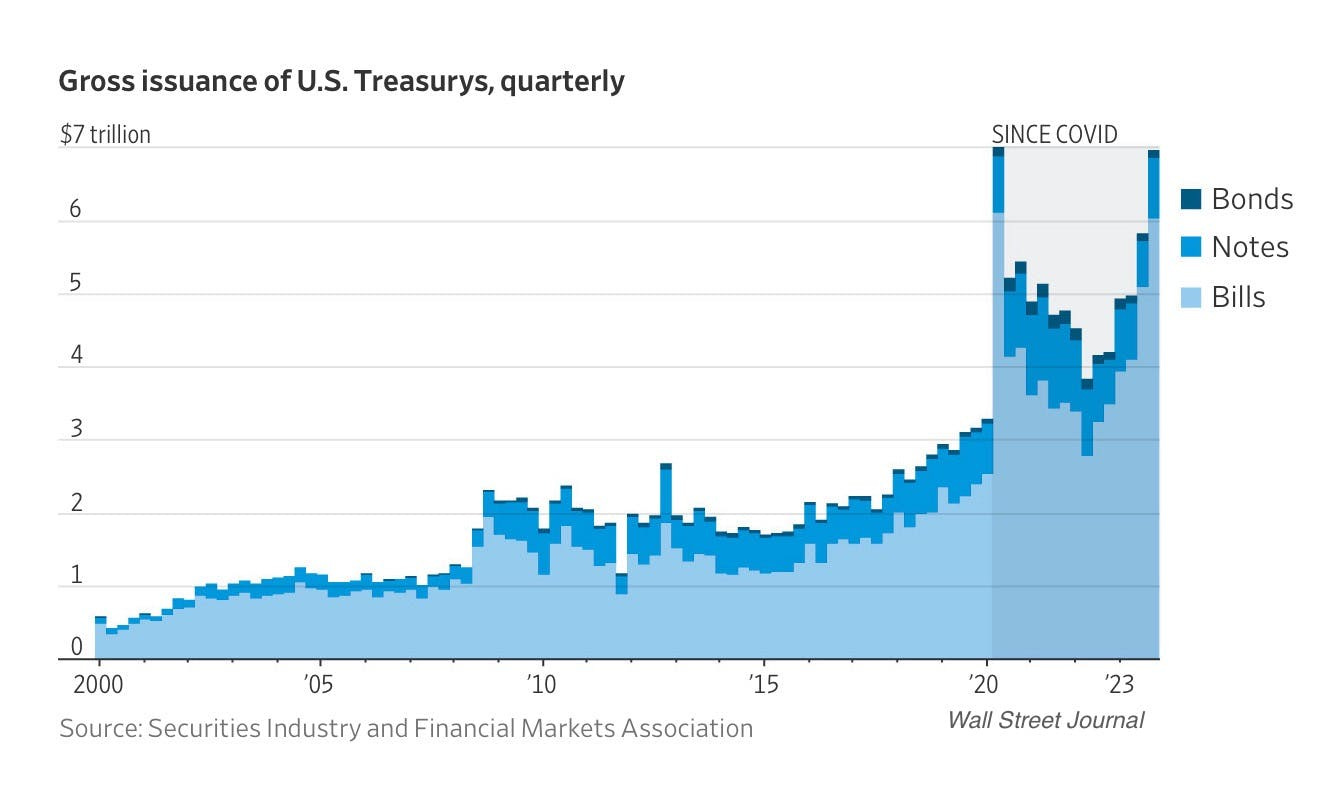

Treasury auctions occur pretty regularly, on a set schedule. About 300 public auctions are held each year, and as you can see here, the US Treasury auctioned about $22T of bonds in 2023.

And this number is only rising.

Big business. One with insatiable demand to keep this whole debt charade going.

See, because the US Government operates in a perpetual deficit (like many fiat-based countries), the Treasury must keep issuing bonds to keep up with the demand for spending.

After all, when a bond matures, we need to issue a new bond to pay off the principle owed To that old bond. This is kind of like opening a new Mastercard to pay off your Visa.

Neat trick.

So, let’s clear up a few terms and definitions (don’t worry, we’ll keep it easy), along with the general rules, so we can better understand what actually happens during an auction.

First, to participate directly in an auction, a bidder must have an established account. Institutions use TAAPS (Treasury Automated Auction Processing System) and individuals use a TreasuryDirect account.

Individuals can only place non-competitive bids, where they agree to accept whatever discount rate (yield) is set by the auction.

Institutions can place either non-competitive or competitive bids, where the bidder specifies an interest rate they are willing to accept.

Institutions can also trade in advance of an auction, and then settle with each other when the auction happens. This is called the when-issued market and is pretty important to our discussion, so we’ll talk more about that in a bit.

Back to the auction itself.

Once an auction begins, the Treasury first accepts all non-competitive bids and then conducts an auction for the remainder of the amount it is looking to raise. This is where competitive bidders are unsure whether they will be filled at their price or not.

The process is called a Dutch auction.

For example:

Let’s say the Treasury wants to raise $100 million in 10-year Notes with a 4% coupon.

Let’s also say it receives $10 million of non-competitive bids.

The Treasury first accepts all these non-competitive bids and reduces the amount left for the Dutch auction to $90 million.

If it then receives the following competitive bids:

$25 million at 3.88%

$20 million at 3.90%

$30 million at 4.0%

$30 million at 4.05%

$25 million at 4.12%

The bids with the lowest yield will be accepted first and then ascend up until the auction is filled. In this case, because the Treasury needs to raise $100 million total, after accepting the $10 million of non-competitive bids, it then accepts all competitivebids up to 4.0% ($75 million) and only $15 million of the 4.05% bids for a total of $90 million.

So, those who bid 4.05% would receive half of their orders filled.

At the end of the auction, all bidders receive the same yield at the highest accepted bid.

The High Yield.

In this case, $100 million of Treasuries were auctioned off at 4.05%.

On the face of it, this looks pretty bad, as the Treasury had to offer a higher yield to raise its target amount.

But how bad? And how can we tell?

Good questions and the answer—per usual with Wall Street—lies in the expectations of pricing. Let’s turn to the metrics of an auction next to find out how.

🧐 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Bid to Cover

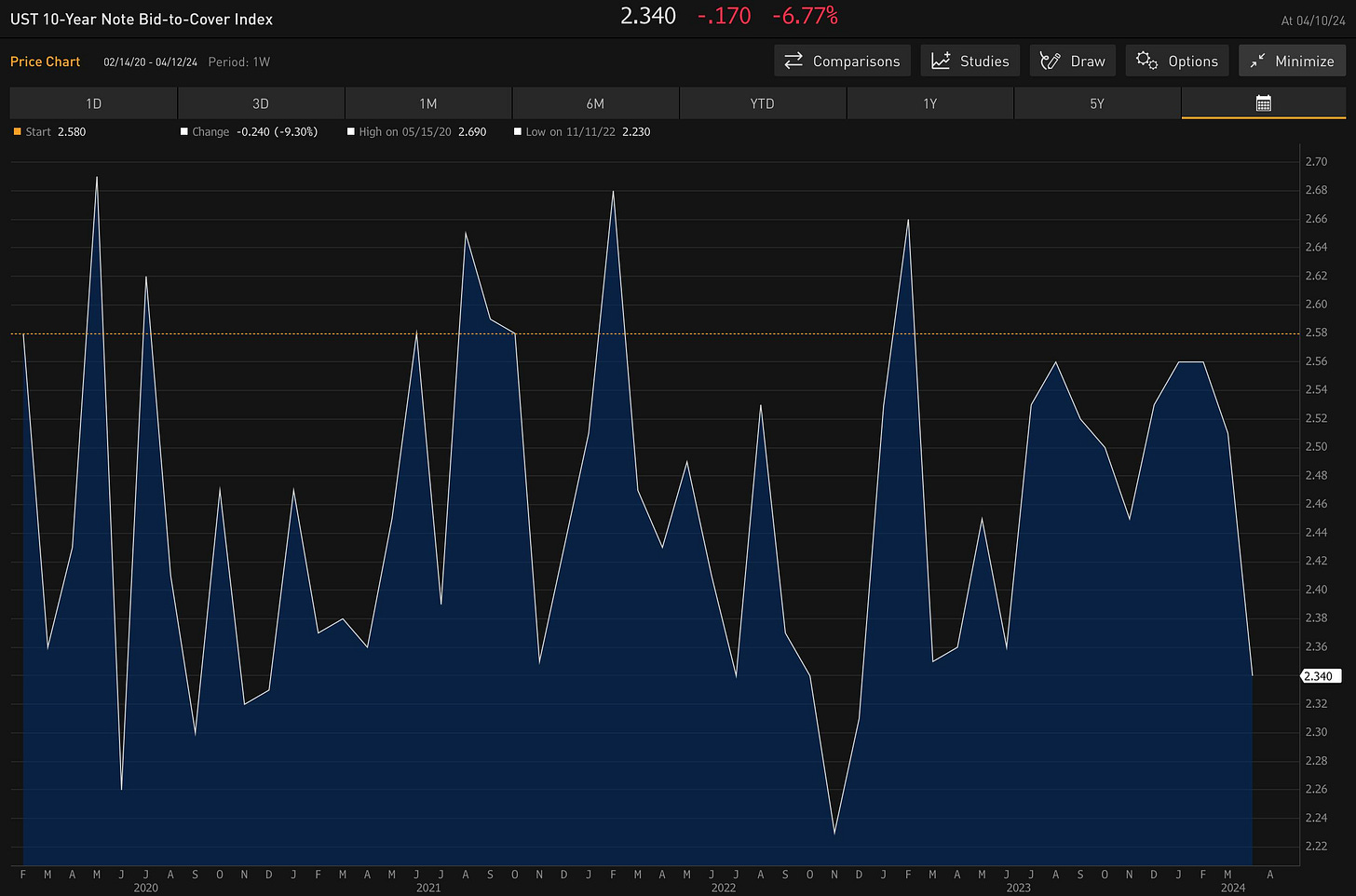

One of the first things traders and investors look for is called the Bid to Cover ratio (sometimes just referred to as BTC). A pretty simple statistic, this is just the total amount of bids received divided by the amount of bond face value of an auction.

In the case above, the total bids amounted to $140 million and the auction was for $100 million of Notes, so the BTC ratio would be 1.4x.

Like many stats, though, what we are often looking for here is a change from prior periods. Is the BTC ratio rising or falling? And how rapidly? If liquidity is drying up in the markets, this would be a pretty good first indicator. If it drops low enough, it’s a major red flag.

More on that in a minute.

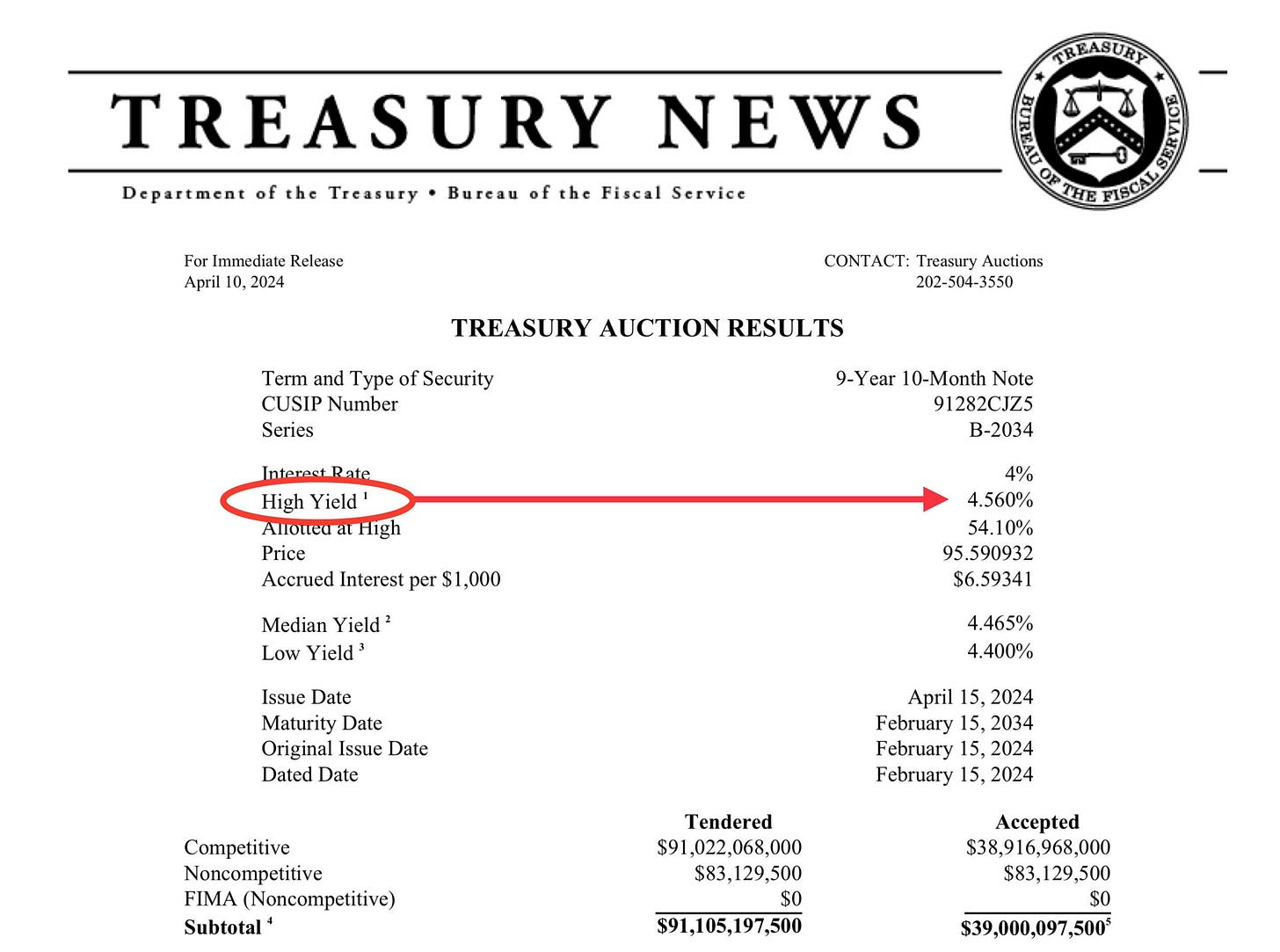

First, here’s the top half of this last week’s 10YR US Treasury Auction Press Release which comes out right after the close of an auction. We can see the yield of the auction was 4.56%.

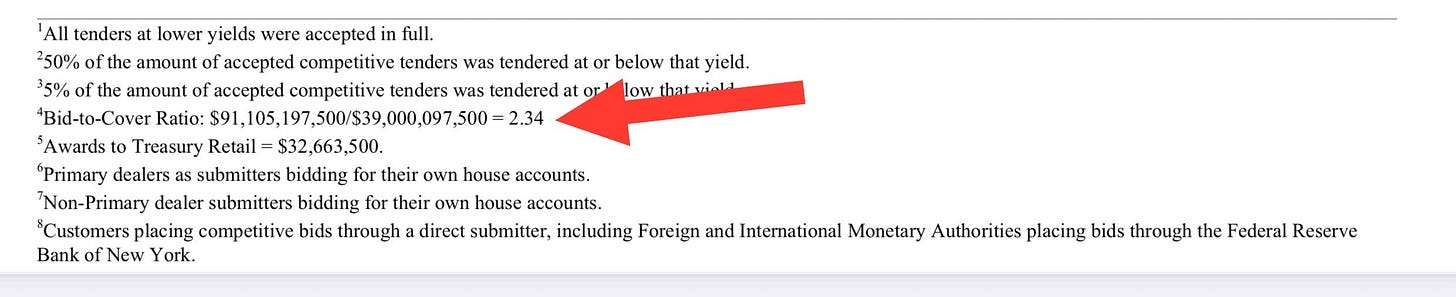

And looking down at the bottom, in the footnotes, we see the auction had a 2.34 BTC ratio.

And looking at recent 10-year Treasury Note auction BTCs, we see this is—as Althea points out above—the lowest BTC in a 10YR auction since late 2022.

Not good.

The High Yield

Another, usually much more important, metric to keep an eye on is the high yield (also called the stop)—the actual yield received by bidders in the auction.

Two things we are looking for here.

Remember how we said these securities trade in a when-issued market before and leading up to an auction? This creates what is called the snap price. It sets the price expectations for an auction and is a critical piece of information for investors.

So, first, was the auction overbid or underbid?

In a case of overbidding, the stop price (high yield) would be lower than the snap price (when issued yield), and this is usually seen as a solid auction. With underbidding, the stop would be higher than the snap, indicating a weak auction.

To put it simply, the snap (when-issued) tells us how the bond traded leading up the auction, and the stop (high yield) tells us how strong the auction was itself. Sometimes a weak auction leaves a tail.

The Auction Tail

The second thing we’re looking for with the high yield, and a bond-fan favorite is called the auction tail.

The tail is the high yield minus the bond’s when-issued yield.

If there is no measurable tail, we say that the auction finished on the screws. A negative tailmeans that the auction went better than expected, with higher-than-expected demand.

But positive tail tells us the auction did not go well because the yield realized in the auction exceeded market expectations, meaning weaker-than-expected demand.

Bottom line, the tail is a measure of unanticipated demand shifts for a Treasury issue before the auction. And the larger the tail, the worse the auction.

Put it this way, if we see a tail with a 4-handle or—God help us—in the 5 or 6bp range, this would be considered disastrous in the bond world and signal nothing short of a dysfunctionalUS Treasury market.

What was this last 10YR UST tail?

3.1bps.

Ouch.

Not catastrophic, but the biggest tail in years and significant. Especially for the 10YR UST, which is considered the global benchmark bond.

Foreign Demand

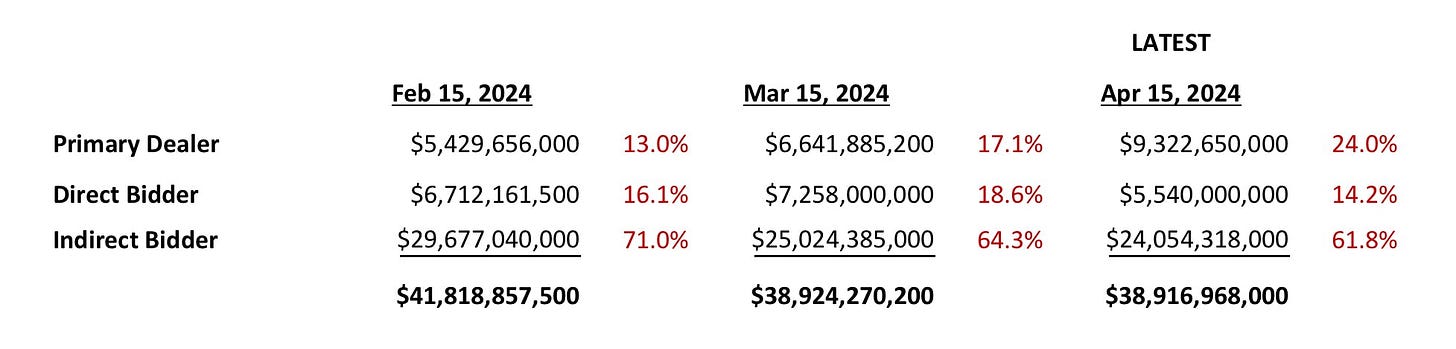

Next, we turn our attention to the demand makeup of the auction. Who bought how much, and what percentages were those splits.

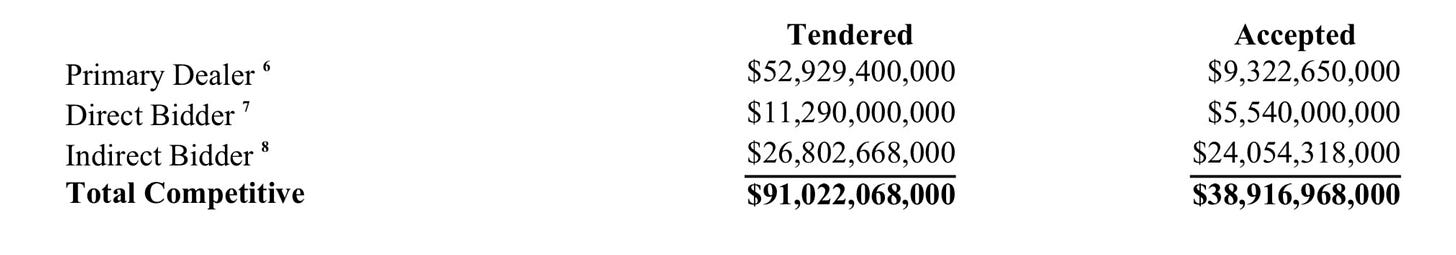

Back to last week’s 10YR auction, let’s add some percentages versus recent auctions to get a feel for the participation strength. The demand.

What we notice here is that the foreign demand (Indirect Bidders) has dropped significantly from 71% just two months ago to 62% for this last auction. And because domestic buyers (Direct Bidders) didn’t pick up the slack—in fact demand dropped there, too—the Primary Dealers were left holding the bag with 24% of the issue! 😱

Not good.

In fact, I would call this abysmal and will be keeping a close eye on 10YR auctions this year.

OK, so now we know that a low BTC could be a red flag, an underbid auction and/or poor participation can be cause for concern, and a big tail is a big no-no, what exactly does it mean when a Treasury auction fails?

😵 Total Fail

Going back to the Bid to Cover ratio, you may have been wondering what happens if the US Treasury holds an auction for a security and they receive fewer bids than the face value of the securities they are seeking to sell.

This would mean the BTC falls below 1, and the Treasury failed to raise as much money as they expected.

In the bond world, this is considered a failed auction, and it would be nothing short of catastrophic for the US Treasury.

So, you may ask, in regards to Althea’s Tweet above, are we headed in that direction? With low demand on a number of recent auctions and falling foreign interest in USTs, is there a possibility of a failed auction on the horizon?

Why yes. Yes there is. But there are a couple of fixes to prevent this before it happens and I don’t think we are in the danger zone.

Yet.

First, US commercial banks are flush with capital. We know this because the Fed is still receiving over $400B of reverse repo purchases daily in the repo window. This is extra cash that these banks loan to the Fed overnight to be paid interest.

If you haven’t read it yet, I wrote a whole newsletter about the repo and reverse repo market. You can find it here:

But this Reverse Repo level has dropped from over $2.5T in the last year, as the Treasury drains it with new T-Bill issuance, and that insatiable demand for borrowing. Once this is gone, the Treasury will have to start tapping the bank reserves, of which there are about $3.5T sitting, right now.

Once this drops below $1T, all bets are off.

In fact, Powell stated he starts to get nervous when they drop to $2.5T.

And with the Treasury borrowing over $2T this year, it doesn’t take a Fields Medalist (aka math genius) to see we are headed straight in that direction.

First, QT will begin to taper soon, if not already. Then it will stop altogether.

And then the dynamic duo of the Fed and the Treasury will circle their wagons, fire up the money printer and make it go BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR.

They will simply have no choice in the matter.

That is…

Unless they want an actual failed auction.

And I put that probability at pretty close to zero.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about Treasury auctions and how to read them for yourself.

If you enjoy The Informationist and find it helpful, please share it with someone who you think will love it, too!

Talk soon,

James✌️